As a child in the 1970s, Charmaine Marcus was forcefully removed from her Cape Town neighbourhood when the apartheid government declared it a whites-only area.

Now, as a property boom transforms once-neglected suburbs into trendy and expensive enclaves, she faces being pushed completely out of the city she calls home.

“It seems to me they just don’t want us here,” says Marcus, who is fighting a pending eviction in court after a dispute with her landlord. “But this is our city. We are this city.”

South Africa’s slowing economy and political uncertainty have curtailed the property market countrywide.

But Cape Town has proved to be an exception, with houses here on average 78.5% more expensive than they were in 2010, according to the South African FNB bank.

Property expert Toni Enderli says the boom is driven by families from across the country moving to Western Cape province, in part because the region has a reputation for good governance under the Democratic Alliance party that is in power at provincial government level.

“The population in the province has gone up 33% in the last 15 years,” Enderli told AFP.

“People want to be in Cape Town, they want the lifestyle. But the supply of houses that should be developed on a yearly basis is not keeping up with that.”

In the suburb of Woodstock, where Marcus has lived for 35 years, the evolution of decayed buildings into modern apartment blocks, restaurants and markets has made it a favourite among young professionals — and doubled housing prices in just the last five years.

Marcus’ home reveals a different picture.

The paint peels off the living room ceiling as a wide crack traces its way down to the floor.

Upstairs, one apartment stands exposed to the elements, gutted.

Residents began withholding their rent here after a fire two years ago ripped through a section of the building, killing one of the tenants.

They blame the landlord for failing to maintain the structure.

He responded to the non-payment of rent by issuing eviction notices.

Based on current trends, the building could be a prime site for redevelopment as modern, expensive flats in future.

If Marcus, 48, and her neighbours lose their eviction case, which, they believe, seems probable as the landlord was acting within his rights, none will be able to afford the area’s new rental rates.

Instead, they will likely be relocated to an emergency resettlement camp on a farm some 30km away.

Wolwerivier, or Wolves River, has neither a clinic nor a school and little access to shops or affordable public transport — which could cost Marcus her inner-city job as a cleaner at a clothing company.

Landlords in South Africa need a court order to evict tenants, but the Constitutional Court earlier this year ruled that a court cannot issue an eviction order that would leave a person homeless.

Many tenants however are backyard-dwellers and have no formal contracts.

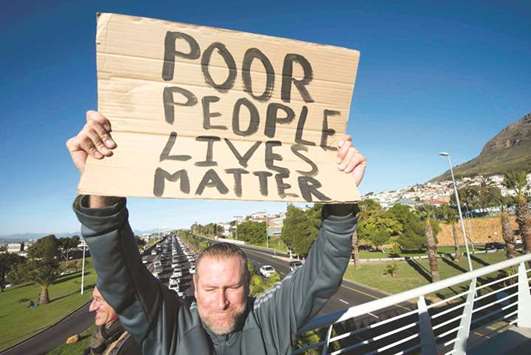

“This city doesn’t work for you, it works against you,” says activist Shane van der Mescht, who is part of a group called Reclaim the City occupying an abandoned hospital in Woodstock where wards and offices have been turned into bedrooms and meeting spaces.

Many of the activists here were sleeping rough until a few months ago, and each has their own eviction story.

“I see them building these apartment blocks, but we can’t afford it,” says activist Ismail Sheik Rahim.

“We feel like outsiders, like strangers in our own country...Where am I going to get 1.4mn rand ($110,000) for a flat?”

Sitting on her front step, Marcus says she knows she will ultimately be evicted from her building.

But leaving her neighbourhood is not an option.

“If the council doesn’t have alternate accommodation for us in or near the city, we’re not going nowhere. We’re here to stay.”

A July 11, 2017, file photo of activist Shane van der Mescht holds a sign during a protest calling for affordable housing close to the city centre for disadvantaged people, organised by the group Reclaim the City, over the N2 highway in Woodstock, Cape Town.