There’s a new kid on the block, muscling in on crude sales to China. America is rapidly carving out a niche for itself, stepping in to fill the gap left by falling supplies from Opec countries.

As recently as last year US crude-oil exports to China were puny. On average in 2016, companies shipped just 10,000 barrels a day to China – that’s less than two supertankers during the whole year.

The US ranked 32nd in the list of Chinese import sources in 2016, according to data from the Chinese customs authorities. That’s below Mongolia and Sudan, and only just above Yemen.

But all that has changed dramatically this year, with US crude exports to China leapfrogging sales from Opec countries such as Libya and China’s neighbours Vietnam, Kazakhstan and Australia.

The upward march extended through the first seven months of 2017. Sales averaged 131,000 barrels a day in the period, but over the last four months the daily average figure exceeded 200,000 barrels.

That is enough to move the US up to 11th place in the ranking of crude oil suppliers to China, putting it just behind Opec heavy weights Venezuela, Kuwait and the UAE.

Opec’s bid to push up prices by restricting output, combined with China’s apparently insatiable thirst for imported oil, have certainly helped open up a market for American suppliers.

So too have low shipping costs and widening discounts for US crude benchmark WTI against both North Sea Brent, which is used as a pricing reference for West African grades, and the Oman/Dubai average, used for pricing Middle Eastern exports to Asia.

Expect the US ranking to gain further ground as producers look for outlets for rising volumes of production, even while the US itself remains a net importer of crude. That may be sweet music to the ears of President Donald Trump, with rising oil sales helping to reduce the trade deficit with China.

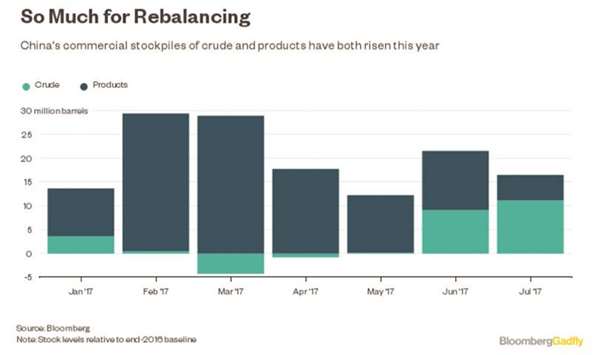

But it will not be so comfortable for Opec countries, who have long seen China and other emerging Asian countries as their core markets. Nor is it helping to drain global stockpiles. While the volume in storage in the US is coming down, the volume held in China is still rising.

Commercial stockpiles of crude and refined products in China have risen by 16.5mn barrels, or 5%, since the beginning of the year. Strategic stockpiles, which are not reported, have also almost certainly increased too. Not exactly the rebalancing Opec is trying to achieve.

With oil demand stagnating in the developed world, Opec producers have turned to Asia, tying up markets with investments in refining and storage capacity in the region. It is no coincidence that initial output cuts by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Opec countries back in January were targeted at buyers in Europe and North America, while supplies to Asian customers were largely unaffected.

Saudi Arabia has already ceded its position as China’s biggest oil supplier to Russia, and this year has also seen fellow Opec member Angola move into second place.

And it’ll be hard to regain that top spot: Russia looks set to consolidate its position as China’s biggest crude supplier once the second string of a pipeline connecting oil fields in East Siberia to Chinese refineries comes into operation in January. That line will allow Russian producers to ship another 300,000 barrels a day of Siberian crude directly to China.

US oil flows to China remain vulnerable to any increase in freight costs or a narrowing of the price differential to other global benchmarks. But while Opec continues to restrict supply, neither of those looks like a big risk.

* Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg First Word.

.