It was at China’s Fuzhou that I first met Ashwini Iyer Tiwari, who was there with her first film, Nil Battey Sannata (The New Classmate being the English title). I was on the jury, a large one with an overwhelming majority of Chinese and just three foreigners. And I think the judges, for whatever they understood of Indian cinema and the nation’s cultural as well as social ethos, liked Swara Bhaskar’s performance in Fuzhou competition title as a house maid in the small city of Agra – legendary for its Taj Mahal, a symbol of eternal love that has also doubled up as the most iconic, most distinguishable image of India.

The maid, who works for a well-to-do family of husband and wife (played by the brilliant actress, Ratna Shah Pathak), dreams of a day when her daughter would become an Indian Administrative Officer, a rank that is synonymous with the higher echelons of bureaucratic power in India. But the little, school-going girl firmly believes that a driver’s son will become a driver, and a maid’s daughter, well, a maid – her thinking driven by her sheer laziness to master mathematics. And so, the maid, encouraged by her mistress, joins her daughter’s class and embarrasses the girl by topping the math paper! We know what happens thereafter.

“I wanted to shoot Nil Battey Sannata there, because the Taj Mahal is a symbol of love, and I wanted the relationship between the mother and daughter to play out against that background,” averred Ashwini in a recent media interview.

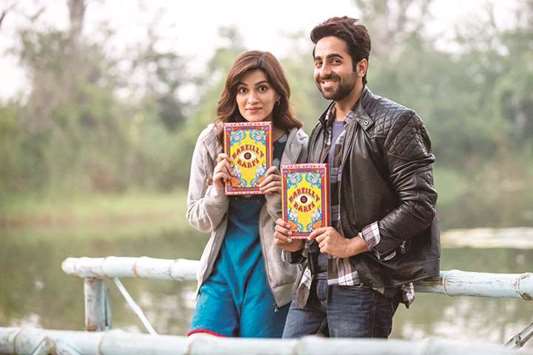

Now, Ashwini – who speaks Tamil and whose long stint in the advertising world took her often to India’s smaller cities, particularly in Uttar Pradesh – has got her second movie popping out of the cans. Called Bareilly Ki Barfi, it has Ayushmann Khurrana (as a printing press owner in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh), Rajkummar Rao (a salesman in a sari shop) and Kriti Sanon, who works for the electricity department also in Bareilly, where her father (Pankaj Tripathi) runs a sweetmeat shop.

The film’s title is take-off on this, and narrates the story of Sanon’s Bitti Mishra – a free-spirited young woman whose cigarette-smoking, boozing and carefree temperament make her most undesirable for the marriage market, filled as it is with prospective grooms dreaming of a bride who will be content being closeted in the kitchen rolling rotis.

But Bitti is none of this, and when she finally decides to leave home, a life-changing event stops her during a railway journey. She picks a copy of a novel, Bareilly Ki Barfi, written by Pritam Vidrohi. Strangely, the woman in the story has an uncanny resemblance to Bitti, whose curiosity stops her in her tracks, and she saunters into the printing press, where the actual author of the book, Chirag Dubey (Khurrana), pretends that it his friend, Vidrohi (Rao), who has penned the slim volume. Chirag had written the novel under his pal’s name, probably fearing social ostracism in the small-town of Bareilly.

What then unfolds is a love triangle – a variation of such luminous works as Cyrano de Bergerac and Hitch, a variation that has been done to done death in Indian cinema. I have seen very early on how Sunil Dutt’s Bhola fools Bindu (Saira Banu) in believing that he is a singer. He is not and gets Kishore Kumar to impersonate. In Saajan, Madhuri Dixit is in love with the dashing “poet” Salman Khan, but it is the physically handicapped orphan, Sanjay Dutt, who pens the poems. We have seen this kind deception, often harmless, in so many other movies, and Ashwini’s work therefore does not score on novelty.

However, what I found quite absorbing about the work was the director’s effort to spread out a canvas where we see life as it exists in India’s smaller cities or towns, where people are still rooted in their culture and are affectionately connected with their families and even friends. But they aspire a degree of freedom, a kind of independence that will free them from the shackles of conservatism. Bittu is a rebel of sorts who smokes and drinks and hits off at Bareilly’s marriage parties with her breakdances. Her father is okay with all this.

But no young man in Bareilly would like to marry her. Yet, Chirag dares to explore such a bindas woman in his fiction, and when he finally meets Bitti, who is like the heroine of his story, he is smitten by her. He falls head over heels in love, but Bitti is in love with author Pritam Vidrohi!

Bareilly Ki Barfi – which is textured well, enacted with passion by the major players – has this remarkable ability to transport us metro-wallas to a small-town ambiance, where the mood is still strikingly humane and warm.

This reminds me of a senior, but youngish Airtel executive who was transferred to Bhopal after years in Chennai. He told me that he and his wife were nervous about the shift and the nature of the people in that city. “But believe me”, he said over the telephone from Bhopal after having lived there for about six months, “the people were extraordinarily friendly and made us – totally alien to their language and way of living – feel welcome. They would never fail to invite us to their family gatherings and festivals”.

It is this sweet spirit of a small town that Ashwini offers as her Barfi.

* Gautaman Bhaskaran has been

writing on Indian and world cinema

for close to four decades, and may be e-mailed at [email protected]

Ashwini’s film captures the sweet spirit of a small town.