First, the good news. The warehouse load-out queues that exposed the London Metal Exchange (LME) to the harsh glare of both media and regulatory scrutiny have gone.

The original queue to get aluminium out of exchange warehouses in Detroit disappeared in April 2016. The even longer queue at the Dutch port of Vlissingen finally dissipated last month. It’s taken five years and a barrage of new rules and regulations to get there.

The breaking of the queue model has spelt misfortune for some warehouse operators and provided growth opportunities for others.

But here’s the less good news.

LME metals storage remains tightly controlled by a small handful of the 30 registered storage providers.

And having repurposed its physical delivery system to facilitate load-out, the LME risks becoming a victim of its own success. Registered stocks are steadily dwindling as metal moves to off-market storage. LME warehouse operators are fighting ever more fiercely for a slice of this diminishing pie, a battle that is now increasingly focused on Asia.

Vlissingen was the last of what the LME at one stage identified as five “embedded” queues.

There are still occasional “flash” queues caused by high-volume cancellations of LME-warranted metal in preparation for physical load-out.

As of the end of July, for example, there was a 25-day queue at warehouses operated by P Global Services at the South Korean port of Busan.

But warehouse operators no longer profit from such bottle-necks and are instead incentivised to reduce them as quickly as possible.

Anyone having to wait 25 days to get their metal pays reduced storage costs or nothing at all if the queue is over 50 days.

Unsurprisingly, the loss of the old queue money-making machine has led to a change of fortunes on the top table of the LME warehousing fraternity.

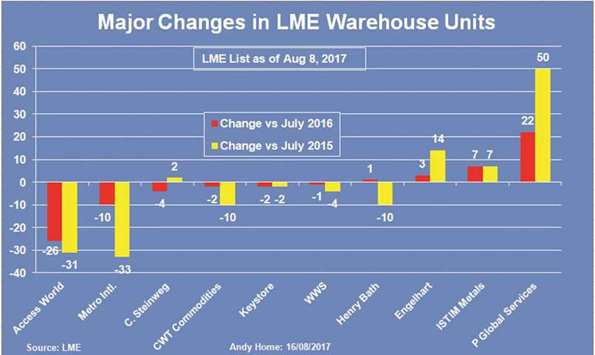

Metro International, which was hit with a retroactive $10mn fine for its role in creating and maintaining the original Detroit queue, has significantly reduced its LME foot-print. It currently operates 33 registered storage units, half the number of two years ago. Access World, the logistics arm of Swiss trade house Glencore and “owner” of the Vlissingen queue, has cut 31 units over the last two years.

That said, with 128 registered units as of August 8, it is still the second-largest operator after C Steinweg.

The biggest “winner” in terms of number of registered storage units has been P.Global Services, which sold its LME warehouse business to Glencore in 2010 but has since reentered the fray.

It has added 50 sheds over the last two years to give it a current total of 61.

Some of the faces may have changed but what hasn’t changed is the concentration of stocks among just a handful of bigger operators.

As of the LME’s most recent report for the month of July, just seven warehouse companies held 95% of all exchange metal stocks.

They were, in descending order: C Steinweg, Access World, P Global Services, ISTIM, Engelhart, Henry Bath and, still, Metro.

Indeed, the top two were storing almost 58% of the stocks between them. That ratio, by the way, is almost unchanged from July last year.

Even these top operators, however, are fighting for dominance in a shrinking arena. The amount of metal registered with the LME has fallen from almost 7mn tonnes in April 2014 to just 2.6mn tonnes at the end of July this year.

Much of what has gone has been aluminium.

And even the most bullish commentators won’t claim that the four mn tonnes of LME outflow since 2014 has been shipped to end-users. Rather, the consensus view is that much, if not most, of it has simply shifted to cheaper, off-market storage.

As aluminium units have slipped into the statistical shadows in both the US and Europe, the centre of LME stocks activity has increasingly turned to Asia.

There are just seven active LME good-delivery points for aluminium in the region but between them they now hold almost 600,000 tonnes of metal, representing 46% of the system total. But this isn’t just an aluminium story.

A breakdown of storage capacity by region confirms a broader shift eastwards.

n Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.

.