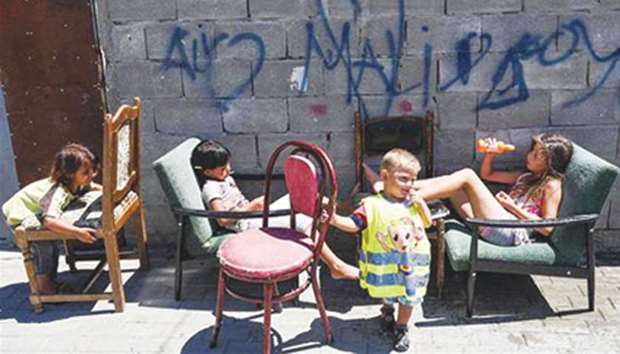

Kosovo’s Roma minority “are not treated as humans,” laments Florim Masurica, who is seeking justice for his disabled son, one of the children suffering from suspected lead-poisoning contracted at post-war United Nations camps.

Kosovo’s pro-independence ethnic Albanian rebels saw Roma people as guilty of co-operation with Serbs during the 1998-1999 conflict – a gratuitous accusation as Roma largely kept out of the fighting.

But some of them faced summary executions, while others were forced to flee from their homes that were looted and destroyed after the departure of Serb forces from Kosovo following a Nato bombing campaign.

That was the case in the Roma neighbourhood of Mahalla in Kosovo’s northern city of Mitrovica.

Around 600 of its inhabitants were given shelter by the UN mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) in five camps, initially meant as a temporary measure for 45 days, but they ended up staying six years.

Living near a heavy metals mining complex, these displaced people were unaware that they were breathing in air and trampling on soil contaminated with lead and other toxins, as scientific tests have showed.

In 2005, human rights groups became concerned by the symptoms of Roma children in the camps such as black gums, headaches, learning difficulties, convulsions and high blood pressure.

UNMIK then evacuated the camps – but for some of its residents this was too late.

Bajram Babajboks, 65, claims that there was no single member of his family — four daughters, seven sons and 60 nieces and nephews — “who is not a victim of lead toxins.”

“It’s the doctors who say it,” he told AFP, showing the latest blood test results.

In February 2006, a panel of experts appointed by the UN – following complaints by 138 Roma – came up with a 79-page report examining the claims of poisoning.

It cited tests conducted by the World Health Organisation in 2004, showing most children in the most exposed camps had “above acceptable” lead levels in their blood and that “more than 80% of soils in the camps were ‘unsafe’ because of lead contamination.”

An environmental medicine specialist, Klaus-Dietrich Runow, took hair tests in the camps in 2005 with “the highest ever seen [results] in the values of heavy metal in human hair samples.”

The panel concluded that UNMIK had failed “to comply with applicable human rights standards in response to the adverse health condition caused by lead contamination in the IDP camps and the consequent harms suffered by the complainants.”

Kosovo’s pro-independence ethnic Albanian rebels saw Roma people as guilty of co-operation with Serbs during the 1998-1999 conflict.