Reindeer eye soup? Animal blood stew? It might sound stomach-churning for people in developed nations, but this is the kind of nutrition that the indigenous peoples of the Arctic region survive on. For thousands of years, they have been feeding off that which nature, and above all the sea, provides them.

But this ancient bond between man and nature is now under threat. Climate change is playing havoc with the region’s natural processes.

The warming of the earth is affecting the Arctic much more harshly than other, more moderate temperature zones. While the world’s nations are battling to stop global warming rising more than two degrees, in the Arctic, they have already risen more than that.

In January this year, temperatures in the Arctic were 5 degrees higher than the average recorded between 1982 and 2010. This is, so to speak, off the charts, and has triggered an entire series of problems.

“We are afraid for our basic nutrition,” says Vi Waghivi, a 58-year-old who for years has been working as an activist on behalf of the indigenous peoples.

Vi has been living for a long time in the Alaskan capital Anchorage, but she was born and grew up on St Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, where on clear days you can see the Russian mainland.

There are two villages, Gambell and Savoonga, on the island, inhabited by about 1,000 members of the Yupik tribe. Vi comes from Savoonga. She explains that 70 to 80 per cent of the Yupik’s diet consists of food acquired through traditional methods, meaning what the sea provides naturally.

Their main food source: walrus. But walrus numbers are decreasing. “The ice is getting thinner,” Vi says. The walruses need ice to help them search for their own food in the sea.

Over the centuries, the Yupik have built up vast knowledge of the ice and have 150 different words in their vocabulary to describe frozen water. But with the warming climate, this knowledge no long counts for much. “In a normal winter, we capture 200 walruses. This past winter it was just five,” Vi says.

The problem is not just that the inhabitants can no longer process the animals’ teeth, bones and pelts, but also that they simply no longer have enough to eat. Now they must buy food.

In remote regions of Alaska, three bananas cost 12 dollars, a twin-pack of cornflakes ten dollars. The food has to be flown in on small aircraft. When Vi travels from Anchorage to her family on St Lawrence Island, the journey takes an entire day – and costs 1,000 dollars.

And on top of all this, the quality of the environment is also declining. Melting ice is releasing bacteria that have been held inside it for centuries – and they are now entering the food chain.

“Our children are starting to experience learning difficulties and the rate of cancer is rising,” Vi says. But resettling elsewhere is no alternative for the Arctic population. “This is part of our identity,” she says.

In the Arctic region, climate change is a very real and dramatic development. “My friends in Oregon tell me, climate change is coming,” says Bernadette Dementieff, who belongs to an advocacy group for the Gwich’in, a nomadic tribe that live along the border between Alaska and Canada. “I tell them, it is already here.”

New studies back her up. The ice in the Arctic has vastly diminished during the past few years. Environmentalists warn of an ecological disaster looming and are demanding action from their governments. The climate targets for the year 2050 must be urgently reviewed, they argue.

But climate policy is faltering. Dementieff and her associates are putting their hopes on the Arctic Council, which consists of the eight foreign ministers – including US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov – of the Arctic littoral states, along with representatives of the indigenous people.

The big question that looms is: What are the climate policy aims of the US? President Donald Trump continues to back old energy sources. He wants to push oil production, pipeline construction and the use of mineral resources in Alaska, even despite warnings from the financial community. A recent study by the investment firm Goldman Sachs said that oil drilling in the Arctic will be unprofitable for decades to come.

The indigenous people of the Arctic region now must wait and see whether his plans will turn into reality, and what effects they will have. “I’ll fight until I melt,” Dementieff says. - DPA

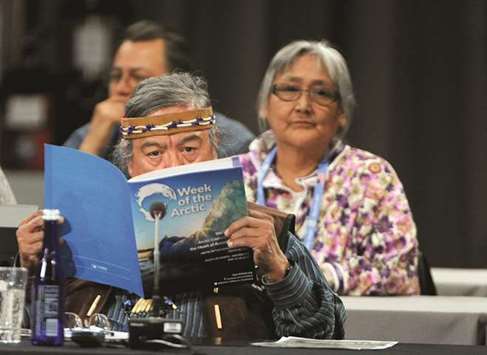

A representative from the Arctic Athabaskan Council during the Arctic Council Ministerial at the Carlson Center in Fairbanks, Alaska in May 2017.