When visitors set foot into Pandora — the World of Avatar at Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, they will find glowing plants and floating mountains.

Opened this week, the lush, forest-like setting of Pandora obviously takes its cues from James Cameron’s 1999 blockbuster; more unexpected is the subtle nod to the Italian Baroque art of Gian Lorenzo Bernini seen in the entangled vines descending from the apparently hovering mountains.

On the other side of the country, fans of Guardians of the Galaxy films will find much that’s familiar in California Adventure’s new Guardians of the Galaxy: Mission Breakout attraction, which also opened Saturday.

Art history majors, however, may also notice the high-tech influence of architect Renzo Piano, who worked on France’s Pompidou Centre.

These cultural mash-ups, which herald a new age and aesthetic for the two Disney parks, are compliments of the complicated mind of one man: Imagineer Joe Rohde.

During his nearly 40 years with Walt Disney Imagineering, the company’s highly secretive arm devoted to theme park experiences, Rohde has emerged as something akin to Disney’s philosopher king, working from a deep belief that Disney parks are cultural institutions as much as they are places to ride alongside pirates or buy a churro and a lightsaber.

Many of Rohde’s ideas about theme park design can be traced back to the original Imagineer; Walt Disney too preached the importance of environmental storytelling (see New Orleans Square) and the belief that the common amusement park could be elevated to something far grander.

But Rohde is more likely to cite Michel Foucault than he is Uncle Walt.

Standing beneath the floating mountains of Pandora — steel structures propped up with some cleverly disguised vines — Rohde referenced the ceilings of grand cathedrals and mentioned the way in which Bernini’s sculptures appear to be constantly in motion.

“The research that goes into these parks is not merely research into the real world,” says Rohde. “It is research into the great works of art of all those who have come before. That’s how it works. This is art.”

Though separated by 2,500 miles, both Pandora and Mission Breakout signal a shift in Disney park culture here in the US. As recent acquisitions and partnerships start more aggressively nestling into the parks alongside Disney traditionalism (up next: Star Wars), many fans have expressed concern about the specific brand of Disney “magic.”

Disney’s rock star

Rohde’s ubiquitous and increasingly visible presences puts this current period of transition in the hands of one of Disney’s more popular Imagineers. Candid and outspoken, Rohde doesn’t speak the language of press releases; he intellectualises every facet of theme park design, capable of riffing at length on, say, the history of tiki bars.

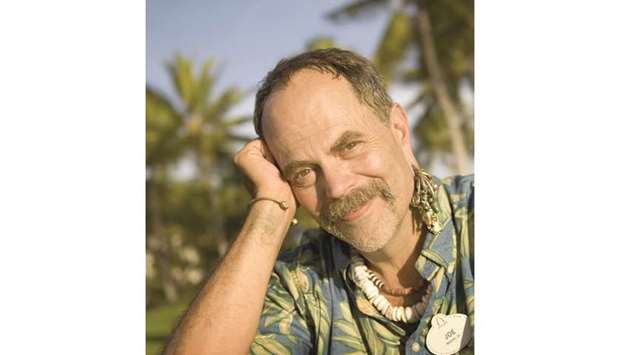

To the Disney-devoted — fans who can react to a remodel of Tower of Terror as if Stonehenge had been scarred with graffiti — Rohde is something of a rock star. He even looks the part, often sporting a safari hat, a 10-day-old beard and beady earrings, which he has collected from trips around the globe, that dangle past his jaw line.

To one of his superiors, chairman of Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Bob Chapek, Rohde is a “legendary Imagineer” and “the father of Animal Kingdom,” the park he has been closely tied to for the last two decades.

To his former boss, the retired and longtime Imagineering executive Marty Sklar, Rohde is a student/teacher who studies projects “with more depth than anybody that I’ve worked with,” but who also understands the power of irreverence, as when he famously pitched Animal Kingdom to then-Disney chairman Michael Eisner by bringing a live Bengal tiger to the presentation.

“The day that Joe brought that animal into the meeting made all the difference in the world,” Sklar says now.

To the 13,000-plus who follow him on Instagram, Rohde delivers brief lessons in art history — one recent post created a rhyme around Italian renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola — while also sharing behind-the-scenes tidbits about the parks (the tables in an Animal Kingdom bar, for instance, are replicas of Asian Bronze Age drums).

As the leader of massive teams dedicated to bringing film-inspired worlds to life, Rohde likens his role to that of a director. His actors are the bioluminescent forests of Pandora or the hyperactive Rocket Raccoon animatronic that guests will encounter early on in Mission Breakout. (If the star of Tower of Terror was its unsuspecting elevator drop, look for the freewheeling Rocket — Anaheim’s most technically impressive robotic critter — to steal the Guardians of the Galaxy ride.)

And in Rhode’s world, no ride — or bridge, or handrail, or lamppost, or piece of moss — can exist without narrative cause.

“In theatre, there are principals, principals of design, and one of those principals is if something is on stage, it is on stage for a reason,” he says from a bridge inside Disney’s Animal Kingdom that leads into the colourful thicket of Pandora.

Rohde talks fast, carefully articulating each word and often repeating them for emphasis as if addressing a classroom. His academic mien makes sense; before joining Imagineering in 1980, he taught art history and theatrical set design at a San Fernando Valley high school.

“There is no such thing as an accident,” he continues, gesturing first toward the metal on the bridge, aged to look rusted, and then to the colourfully alien light fixtures. These contrasts, he explains, are designed to illustrate that different cultures, at different time periods, have laid claim to this bridge.

“There is no such thing as a coincidence because that misleads you in terms of the story,” he says. “The detail does not exist to serve its own purposes. It only exists to serve narrative purposes.”

In 2011, when Disney first unveiled its plans to bring the universe of Avatar to Animal Kingdom, fans wondered how the war-focused sci-fi film would vibe with the park. Animal Kingdom, after all, puts an emphasis on realism — living, not mechanical, animals, and themed-lands based upon true-life versions of Africa and Asia.

As the land was being built, and an Avatar sequel continued to be delayed, currently all the way to 2020, some began to question the movie’s lasting relevancy. “It’s mostly a forgotten film at this point,” says Todd James Pierce, host of the Disney History Institute podcast and author of Three Years in Wonderland, a book about Disneyland’s creation.

Rohde is happy to explain that Pandora’s mission is bigger than nodding to any film, that it actually pivots away from the film. Set a full generation after any cinematic conflicts, Disney’s Pandora is arguably more closely aligned with Animal Kingdom than it is Avatar.

“It’s just like, there’s a movie called Out of Africa. You can go to our Africa,” says Rohde, “but Meryl Streep is not going to pop out of a door. The planet of Pandora is real. You’re on it. James Cameron made some movies (about it).”

The park’s interpretation reflects, says Jon Landau, Cameron’s producing partner, the “ethos” of the film rather than its plot or characters.

“The idea that we could create a theme park that matched philosophically into the movie’s themes was not something Jim and I had thought about, but made perfect sense when it was presented to us,” says Landau.

Pandora also exists as something of a grand metaphor — a reflection of the dangers of environmental waste and the need for animal protection efforts. “We took cues from the film, but if there’s an opportunity to talk about things that are bigger — ecology, conservation — this is it,” says Imagineer Lisa Girolami, the producer on the project.

“I would stop far, far short of calling it educational,” says Rohde, “but it is about validating the experience and making that experience real. That’s a form of play. Play can often be trivialised as something without substance. But actual play — real play, psychological play, a play that is studied — is all about growth, is all about discovery.”

Mission Breakout was designed and built with the same attention to philosophic and physical detail

Surveying the almost-finished attraction in Disney California Adventure on a day in mid-May, Rohde explains that the ground surrounding the structure will soon be disrupted, made to look as if the tower fell from outer space. The thesis here is also derived from its source material. “You go back to the core of heroes and heroism that it comes from,” Rohde says. “These events just appear out of nowhere. It’s the essence of the brand.”

Nods to the past

Inside the tower, the former hotel is populated with otherworldly trinkets, some from Disneyland’s past (a sculpture of the Haunted Mansion’s ghost dog) and some straight from Marvel’s history (a robotic Cosmo the Spacedog).

Whether working with Animal Kingdom, Pandora or superheroes, Rohde says the job is the same: distil the work down to its themes. For Pandora, that meant focusing largely on environmentalism. For Mission Breakout, it meant irreverence.

Such is the key to making mass art of the theme park variety.

“It’s a classic, frankly, high school comp lit course,” Rohde says. “The Great Gatsby. What are the themes of The Great Gatsby? What are the themes of Moby-Dick? Extract the themes from the subject and work to the themes.

“The subjects will distract. The themes will not.” —Los Angeles Times/TNS

u2013 Joe Rohde, Disney Imagineer, on how he conceives theme parks