Now that he’s become France’s new president, Emmanuel Macron will soon be confronted with a job he left unfinished when he resigned from the Economy Ministry in August: Reducing the 19.7% government stake in carmaker Renault SA back to 15%.

The unfulfilled pledge is just one example of potential divestment that Macron may consider as he inherits the second-largest budget deficit in the European Union, seeks funds to revamp France’s ailing nuclear industry, and considers alliances for some companies in which the government owns stakes. Macron, a former investment banker, recently left the door open to cut the government’s 23% holding in phone company Orange, while setting red lines that limit his options.

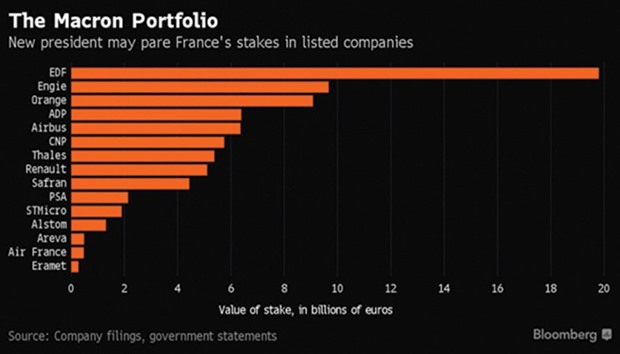

Asset sales would be a further step in France’s long-term trend of slowly paring its stockholdings. The nation is unusual among big western European countries in that it has a broad portfolio of stakes in publicly traded companies, in addition to closely held businesses such as military shipbuilder DCNS and lottery operator Francaise des Jeux.

“We expect him to pull away in certain cases, especially to get out of the holdings that aren’t strategic for the government and to recover some liquidity that way,” said Anne d’Anselme, a fund manager at Cogefi Gestion in Paris. “Those are the types of considerations he carried out in the past” as an investment banker.

Macron, who took office on Sunday, will be selling into a rising market — the benchmark CAC-40 Index reached a nine-year high this month — amid a growing appetite among international investors for shares of European companies. A spokeswoman for the president declined to comment on possible asset sales.

In addition to his own set of criteria for the state’s role as a shareholder, the new president’s options are limited by legislation that obliges the state to keep at least 70% of Electricite de France, 50% of Paris airport operator Groupe ADP and a third of energy company Engie. However, a law that gives double voting rights to long-term shareholders gives some leeway to the government, which allowed it for instance to sell a stake in Engie this year.

While Macron wants to keep strategic assets under the government’s influence, he aims to lower its stakes in some companies to about 18%, which would allow the state to keep a potential blocking minority during shareholder meetings thanks to double voting rights, according to a senior executive at a company in which France holds a stake. The executive asked not to be identified because the matter is confidential.

His decision as economy minister to introduce double voting rights for long-term shareholders at Renault, against the will of chief executive officer Carlos Ghosn, created a row with Nissan Motor Co, which owns 15% of Renault, though doesn’t exercise voting rights. Macron boosted the French government stake by 4.7%, giving it a big enough holding to impose the double voting rights at a shareholder meeting. The state has yet to deliver on Macron’s two-year-old promise to pare back the holding.

Orange’s attempt to take control of most of Bouygues Telecom failed in April 2016 when Macron was still economy minister, and some people familiar with the matter partly blamed at the time Macron’s reluctance to cede too much control of Orange in a proposed share swap. More recently, he signalled the state is willing to pare its stake.

“Orange is neither a company from the nuclear or the defence industry, nor a company providing a monopolistic public service,” he said in an interview published by ElectronLibre on April 13. “The state’s stake in a company like Orange can change. However, the state is playing a stabilising role in the shareholding at Orange, while the industry is going through big changes.”

Macron’s election may rekindle speculation about the consolidation in the industry, Oddo analyst Matthias Desmarais wrote in a May 5 note. The other companies in which the state is most likely to pare back its stake include Renault, Engie and ADP, the analyst noted.

The government’s most valuable holdings include an 83% stake in EDF, 29% in Engie, 11% in Airbus, 51% in ADP, 26% in defence company Thales and 14% in aircraft-engine maker Safran.