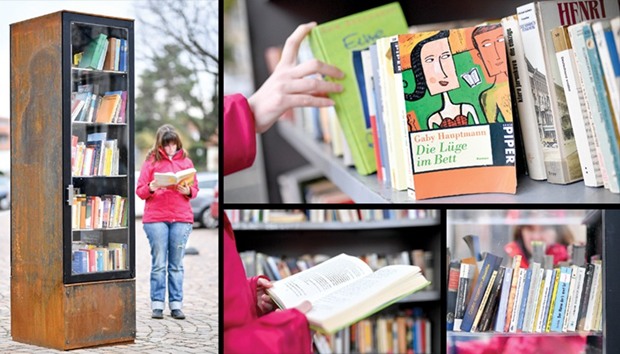

Cities across Germany are putting bookshelves

out on streets and letting everyone take, borrow

and replace books as they please. But will the

experiment be abused?

It’s easy to access, always open and you don’t have to return what you borrow: more and more local councils in Germany are trying to encourage people to read by placing bookshelves out on streets and squares.

“Anyone can come, whenever they want,” says Cornelia Holsten, who introduced the idea to the city of Karlsruhe. “There’s always something going on at the bookshelves.”

The free books create a feeling of community, adds Martina Schickle from Freiburg city council.

“Bookshelves are there to be used and they encourage communication,” she says. Lots of cities and towns are showing interest in the idea and bookshelves are popping up all over the country, from Berlin to Hanover, Darmstadt to Halle.

Since December, the city of Heidelberg has had an enormous metal cupboard in its Handschuhsheim neighbourhood containing dozens of books from all kinds of authors including popular postwar novelists Heinz G Konsalik and Utta Danella, children’s book author Janosch and adventure novelist Karl May.

Birgit Alt flicks through Kevin O’Brien’s detective novel Unspeakable.

“I’ve been wanting to read this book for ages,” says the 47-year-old, who came across the book shelf by chance. “Now I don’t have to go to the library.”

The project is run by the Handschuhsheim Future Workshop (ZWS) and the 7,000 euro cost is paid for by the city, ZWS, and the Civic Foundation of Heidelberg (Buergerstiftung Heidelberg) as well as donations.

Lots of people bring books they no longer want and the shelves are intended to work on the principle of people giving as well as receiving.

“I was sceptical when it started here,” says pensioner Wilhelm Grubba in Neugasse street, where the civic foundation put its first bookshelf in 2010.

“I was worried that the shelves would be destroyed by vandals or would just attract dirt in bad weather,” says the 74-year-old. But his fears have not been realised. Now and then someone leaves a tattered newspaper on the shelves.

“But that’s a seldom occurrence,” says Grubba.

Karlsruhe hasn’t experienced any problems either.

“I think people are still respectful of books and their authors’ efforts,” says Holsten.

She gets lots of books from household clearances. “Old people go into care homes and they give us their books. Otherwise they’d just go into the recycling. Second-hand booksellers just pick the best ones out.”

Holsten doesn’t see the bookshelves as competition to libraries. “Quite the opposite. The unbureaucratic way of doing things is an introduction to books for many people. Young people take part too because they save money that way.”

Children are often enthused. In the city of Tuebingen, Lena and Lisa regularly check out the shelves on their way home from school.

The next morning they often bring another book to replace the one they’ve taken, the 12-year-olds say.

But Alex, a student, is sceptical. “It can’t work in the long term,” he says. “Most people these days have been spoiled by our consumer society and just want to take, take, take.”

Bookshop owners are fairly relaxed about the free books.

“The shelves have a random collection of older works,” says one employee at a shop in Mannheim, where there’s a similar project called “Literature To Go.” “Those who are looking for a particular book will still come to us.”

There have been reports of books being taken from the shelves and sold online or at flea markets. But Sabine Schminke of Tuebingen city council says that’s not her experience and she doesn’t see them as competition to book shops and libraries either.

“In libraries there’s a very deliberate selection, which is orientated according to demand. They also get proper advice. Free book shelves can’t offer that.”

What aren’t wanted are newspapers and outdated books like “Guide to Windows 95.”

That’s why the organisers regularly sort through the shelves to prevent them from becoming rubbish dumps. -DPA

Public bookshelves like this one in the German city of Heidelberg allow readers to borrow and keep books as they please.