What you see is not what you get. This is a truism for any metal stored in London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouses but it is particularly relevant in the lead market right now.

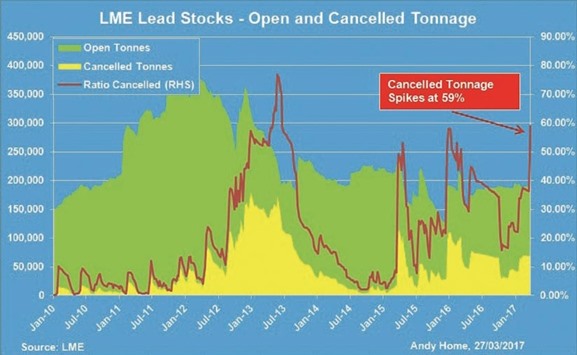

At a headline level there is plenty of metal in the LME storage system, 190,200 tonnes of it.

The year-to-date change has been a marginal decline of 4,700 tonnes.

Scratch beneath the surface, though, and things look very different.

After a second major raid on LME lead stocks last week, only 77,925 tonnes of that headline figure are in the form of “live” warrants, available for contract settlement.

All the rest of it, 112,275 tonnes, or 59% of the total, are now in the form of cancelled warrants, available for physical load-out but not for LME trading purposes.

This scramble for units leaves the London contract vulnerable to cash-date tightness.

But will paper market tightness be accompanied by physical market tightness? Because that seems to be the rationale for the double-wave of LME stocks grabs this year.

The LME’s daily stocks report released last Tuesday (March 21) showed total lead cancellations of 43,625 tonnes, split across the Dutch ports of Vlissingen (33,150 tonnes) and Rotterdam (5,600 tonnes) and the Belgian port of Antwerp (4,875 tonnes). It followed a similar-sized raid in January with the South Korean port of Busan accounting for the bulk of that month’s cancellations.

LME lead stocks have seen this sort of mass cancellation before.

Metal departed one location only to reappear in another location a month or so later, a sure sign that warehousing storage costs rather than a physical shortage of units was the primary driver.

This time appears to be different with all the market chatter suggesting that metal is being hoarded in expectation of a tightening physical market.

And, perhaps tellingly, while the January stocks raid was laid at the door of the “usual suspects”, namely the handful of trading houses that are involved in physical lead merchanting, the most recent was attributed to a new face on the lead block.

The lead story, it seems, is starting to attract a wider audience.

LME open tonnage is now at its lowest level since May 2013, when it touched 52,600 tonnes, itself the lowest level since 2009.

This shrinkage in liquid stocks promises more tension across the front part of the LME lead curve.

The benchmark cash-to-three-months spread flexed out to a $25.25 per tonne backwardation at one stage in January.

It ended last week valued at a relatively benign $10.50 contango but further tightness looks to be a question only of time unless exchange stocks rebuild soon.

But what of the physical market? Lead bulls argue that this too will tighten up later this year, following a similar trajectory to that mapped out for sister metal zinc.

As with zinc, there is already tangible evidence of tightness in the raw materials supply chain.

Treatment charges for lead concentrate are currently at multi-year lows of around $20 per tonne, meaning smelters are having to accept wafer-thin conversion margins simply to get in enough material.

And as with zinc, the betting is that this scarcity will translate into a similar shortage of units in the refined lead market...

Quite evidently, it’s not happened yet. If it had, the metal that was cancelled in January would already have been loaded out of the LME system.

But it has largely stayed in place, biding its time. This unfolding bull lead story, mirroring that in zinc, is all about timing.

But is it a fast-fuse narrative or a slow burner? Bulls hoping for the former will take heart from a surprise in the most recent Chinese trade figures for the month of February.

Imports of lead concentrate continued declining over the first two months of the year, attesting to those stresses in the raw materials part of the supply chain But imports of refined lead also jumped to 9,500 tonnes in February.

That may not sound like much but the last time China imported so much refined lead in a single month was in June 2009.

The country has tended to be a small net exporter in the intervening period.

Since China is particularly exposed to any concentrates tightness due to the size of its smelting-refining sector, it’s tempting to see this jump in metal imports as a sign that tightness is already being transmitted into the refined market.

One month’s data, however, does not a trend make.

There are no obvious red flags that China is running short of lead metal.

Stocks of lead registered with the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) have risen by 45,450 tonnes since the start of January to a current 74,176 tonnes.

The structure of the Shanghai contract is one of contango through August this year, implying no pressure on spot availability. And the arbitrage with London which briefly opened to imports prior to the end of 2016 has closed again.

The next few months’ trade figures out of China will bear close scrutiny.

But there is little to suggest right now that February’s import spike is anything other than a fleeting arbitrage-driven phenomenon.

* Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are those of the author.

.