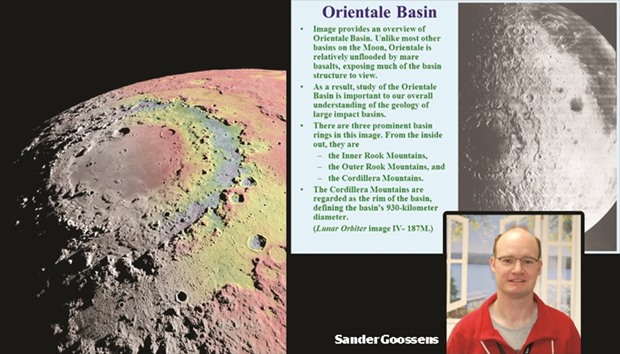

A dramatic feature at the edge of the near side of the moon,

known as the Orientale basin, remains a well-preserved

artefact of the early solar system, writes Scott Dance

About 3.8 billion years ago, something massive slammed into the face of the moon, leaving behind a crater some 560 miles wide.

On most any other object in the inner solar system, the crater would have vanished long ago. Plate tectonics on Earth slowly yet continuously wipe away most record of asteroid impacts such as the one that killed the dinosaurs. But a dramatic feature at the edge of the near side of the moon, known as the Orientale basin, remains a well-preserved artefact of the early solar system.

A new analysis by University of Maryland, Baltimore County scientists reveals that the basin is more than just a big hole. Data captured from a 2012 NASA mission show minuscule changes in the pull of the moon’s gravity at varying points across the crater, suggesting a complex structure with varying density beneath the surface.

“It’s not as simple as punching a hole in the surface of the moon, and whatever hole was made is the final crater,” said Sander Goossens, an associate research scientist at UMBC’s Center for Space Science and Technology. “There’s lots of settling and changing going on after the impact.”

Scientists understand relatively little about what happens when such massive collisions occur in space because there is so little evidence of them on Earth. But the moon provides a window into a time when that sort of cosmic violence was much more common, and shaped the solar system as we know it today.

“You can still get an idea of what things were like in the early solar system,” Goossens said.

The research was published in the October 28 issue of Science — with an image of the close-up view of the Orientale basin featured on the journal’s cover.

The data the researchers analysed came from two spacecraft sent to the moon on a mission called the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory, or GRAIL. In 2012 and 2013, the mission made news for its unprecedented look at the nearest celestial body to Earth.

The two spacecraft scanned the lunar surface in tandem, and when they passed over mountains, valleys or underground features that caused tiny variations in the moon’s gravity field, they would move slightly closer together or farther apart. Scientists measured those minute shifts to chart the moon’s entire gravity field.

The resulting gravity field map is the clearest ever created using satellite data, NASA officials said. They expected to see variations in gravity down to areas about 18 miles across, but ended up flying so close to the surface — less than two miles up — the resolution was almost 10 times sharper, Goossens said.

Some of the richest data was captured at the Orientale basin, he said.

The feature long has fascinated scientists, who first captured images in the 1960s revealing its ringed bull’s-eye structure, evidence of an impact crater.

But they know relatively little about what happens when such craters form, and how they change over time. For example, scientists have theorised that the concentric rings that radiate from the centre of Orientale and other craters form as the initial crater collapses over time.

“Nobody understands what forms these rings,” said Gregory Neumann, a research scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center who worked with Goossens on the research. “Nobody agrees completely on how they’re formed.”

The GRAIL data has shed some light on that mystery. It suggests that the crust is thinnest at the centre of the crater, where the impact of whatever object struck the moon sent a massive chunk of moon rock and mantle bouncing outward into space.

The crust gets progressively thicker farther out from the crater’s centre, but that thickness undulates like a wave.

“It’s like throwing a rock in the water, and there’s all the ripples,” Goossens said.

The data suggest that the original crater was 320 to 460 kilometres wide — about 200 to 300 miles — and that about 3.4 million cubic kilometres of lunar matter was launched into space. The moon’s gravity caused the crater to gradually collapse and widen, the UMBC scientists suggest.

Similar phenomena were recently reported to have occurred on Earth some 66 million years ago when an asteroid believed to have killed off the dinosaurs struck near Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

Researchers said last month they had found that Earth’s crust behaved like a liquid when the asteroid slammed into it, sending rock splashing upward at heights twice as tall as Mount Everest and then collapsing back down, leaving behind a ring of mountains.

In both cases, those mountains, known as a peak ring, have worn down and collapsed over time. But Orientale provides a clearer picture of the phenomenon, the researchers said.

In some cases of asteroid strikes, the initial splash-back of material can actually leave behind a mound in the middle of a crater, Goossens said. But the observations of Orientale suggest the impact was so large that matter all collapsed back on itself, leaving a dense core at the centre, he said.

Orientale is considered a specimen for planetary scientists looking to better understand how planets were shaped in the early solar system, some 4.6 billion years ago.

At its age, it is one of the moon’s youngest large craters, with relatively few smaller, newer craters within its bounds.

“We’re understanding more about the early formation of the Earth as well as the moon,” Neumann said.

“All of the inner solar system has these big impact structures that date back to a time when there were a lot of catastrophic episodes in the solar system that more or less ended around the time of Orientale.” — The Baltimore Sun/TNS

BACK TO BASIN: This false-colour image shows free-air gravitational anomalies and a shaded topographic relief of the Moon’s 930km-diameter Orientale impact basin. (Inset photo) Sander Goossens