President Sergio Mattarella is consulting a total of 23 parties to help him find a successor to outgoing Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, showing how little progress Italy has made in reducing political fragmentation.

Yesterday and today Mattarella will meet separately with groups that few Italians have even heard of, such as the Thought and Action Party, the Civic Innovators Party, and one known only as “Fare!”, which would roughly translate as the “Doing” party.

Several of the delegations holding talks with the president are actually mini-coalitions.

The total number of movements in parliament is around 40.

The first group to emerge from the meetings in Mattarella’s sumptuous Rome palace yesterday recounted their encounter in German.

They represented the Austrian minority in the South-Tyrol border region.

The first significant party to speak, the right-wing Brothers of Italy, which polls say is backed by some 4% of voters, called for an election as quickly as possible.

The party’s leader, Giorgia Meloni, told reporters that it would only back a government tasked with reforming the electoral law “in a few weeks” to allow a vote by March.

The fragmentation of politics into countless parties and factions is one of the reasons Italy has had 63 governments in the last 70 years.

Until the early 1990s, an electoral system of proportional representation (PR) was widely blamed for allowing small parties to prosper, yet since pure PR was scrapped in 1993 the fragmentation has only got worse.

To preserve their existence at elections, tiny parties merge into coalitions, but then often splinter again and change names and allegiance once the new parliament has been formed.

At the same time, single parliamentarians move freely between parties from one election to the next, often changing the make-up of the majority backing the government.

In the first 18 months of the current parliament, 116 of the 315 senators elected in 2013 changed their political colours.

The cause of Italy’s latest political crisis was Renzi’s decision to resign after failing to get popular support for constitutional reforms aimed at increasing government stability.

Critics said one weakness was that his proposal did nothing to prevent party-swapping.

Renzi’s own centre-left government was propped up in parliament by centre-right splinter groups that abandoned Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party after the last election.

Today Mattarella will meet the country’s largest forces: Renzi’s Democratic Party and the opposition, anti-establishment Five-Star Movement.

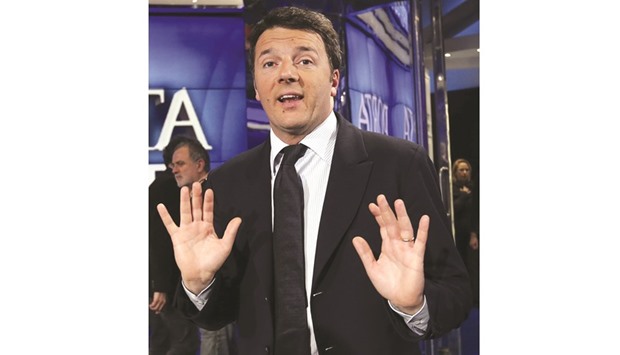

Renzi: tried, and failed, to reform the political system.