Today’s global market has produced a paradox in the craft industry. While globalisation is creating markets and opportunities for traditional handicrafts, the artisan is at the same time weakened and disconnected from markets and consumer needs.

At a time of mass production, when everything is available everywhere, objects with a genuine local and cultural connection become increasingly popular and have an added value for consumers. But for the sector to develop into its full potential the artisan needs to be acknowledged both as a custodian of tradition as well as an entrepreneur.

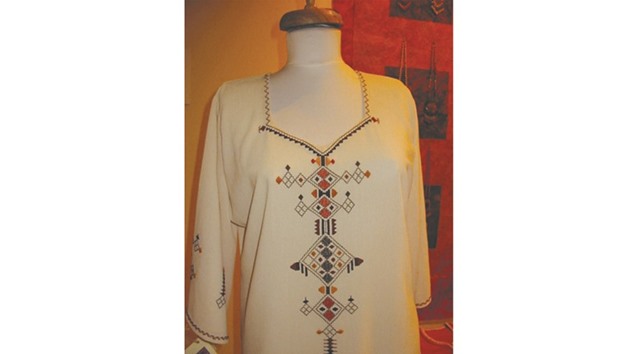

These two visions of crafts, as part of the cultural heritage and as a creative industry are more complementary than opposite. Craftspeople do not simply preserve and safeguard cultural heritage but also enrich and adapt this heritage to the contemporary needs of societies. In this process, artisans need to work closely with designers to facilitate access, adaptation and use of traditional motifs and designs while responding to changes in consumer needs, fashion trends and usage preferences. Through this process they reactivate local markets and develop urban and export markets.

It might be that craft items are tangible but the knowledge and skills that are behind their creation are intangible. The survival of such living traditions depend on the existence of a market environment that stimulates, supports, and promotes the artisan’s creativity and not only his or her product. Since my first contact with craftspeople some 35 years ago in Africa, I have been struck by the huge gap between their talent and their recognition in society. They are creators of beauty – and of revenue – yet they do not enjoy the social status and protection they deserve. By contrast, it is striking that in a world of global mass culture, the “stars” of the day, whether film celebrities, musicians, or sports champions, are idolised disproportionately to their creative role in society.

If one considers that creativity is the only resource equally distributed around the world, the importance to create a favourable environment to stimulate, develop and promote the creativity of craftspeople becomes more evident. What is needed is comprehensive policy based on three pillars: co-ordination, complementarity, and co-operation.

Co-ordination is necessary to make an efficient use of the human, material, and financial means available to address the common problems facing craft persons: training and skills development, regular provision of imported raw materials, and the need for product development and proper marketing at national, regional, and international levels.

The fact that crafts, and the market for it, is a multi-faceted arena where cultural, social, and economic concerns all meet calls for complementarity. The crafts sector cannot develop fully without connections to other key sectors, such as education (for the transmission of traditional knowledge), environment (for renewable raw materials), tourism (namely cultural and eco-tourism) and trade (for exports of representative products). The ‘Creative Economy Report co-published by Unesco and UNDP in 2013 argues, with facts and figures, that creativity and culture have monetary and non-monetary benefits that can contribute to human development. It is, therefore, essential to insert consideration of crafts into these broad frameworks and to relate it to issues such as youth employment, gender equality, and poverty eradication.

Finally, the fierce competition in the global marketplace demands strategic co-operation. This means networking among artisans, entrepreneurs, private and public sectors, NGOs. Craft networks can be of three types: Local (Associations, Guilds, Co-operatives); Regional (such as the Central Asian Craft Support Association-CACSA) and International (World Crafts Council-WCC; IRCICA). The common objective of all the concerned partners should be to highlight the role of crafts as the expression of a rich cultural heritage and as a cultural industry ensuring a means of earning a living for craft persons and their families.

* Indrasen Vencatachellum is the former director of Unesco’s Division for the Diversity of Cultural Expressions and Creative Industries. Since 2008, Independent Consultant in Culture and Development projects for EU, UNDP and Unesco. Currently based in Paris, he is the Co-ordinator of the International Network for Craft Development – RIDA (www.ridanet.org) and secretary general of the NGO Culture of Origins. Next Tuesday Salma al-Noaimi, cultural consultant at Katara will be writing on the current state of Qatar’s traditional handicrafts and future aspirations for the sector.

Modern dress with traditional touareg designs (Copyright: Indrasen Vencatachellum)