The recent Tokyo International Film Festival offered a sumptuous buffet of movies from many corners that told us how men and women were grappling with challenges while travelling through paths of horror and fantasy, pain and pleasure as well as tragedy and comedy. Here are a few dishes laid out at Japan.

*****

Clinching the Festival’s top honour, Tokyo Grand Prix, Chris Kraus’ romantic German drama, The Bloom of Yesterday, was utterly enjoyable even though it was talking about a subject as gruesome as the Holocaust. Played out by two excellent actors – Lars Eidinger (recently seen in Oliver Assayas’ Personal Shopper and Clouds of Sils Maria) and Adele Haenel (Dardennes’ brothers The Unknown Girl) – the film was a delicious combo of the comic and the tragic.

Toto (Eidinger) – whose grandfather was a notorious Nazi war criminal – is a Holocaust scholar with a wife and an adopted daughter. He is all set to pilot a Holocaust conference, and when an intern, Zazie (Haenel), the granddaughter of a French Holocaust victim, enters the scene, a war of sorts between her and Toto erupts, a war that is fuelled by guilt and anger. And when Zazie asks Toto what his granddad was like, he fumbles for an answer before blurting out “kind”. A tempest is unleashed, and despite a hot sexual chemistry between the two (never mind Toto assumes he is impotent), they find it difficult to bring to a closure a chapter of history that neither of them was a part of.

Kraus fills his narrative with rib-ticklers, and one that has stayed with me is a scene where Zazie refuses to get into a car which she thinks is one of the kind that took her grandmother to the gas chamber. The movie has been wonderfully put together – glossily photographed and attractively sound tracked. And despite fisticuffs and boisterous banter – some between Toto and his colleagues planning the conference – The Bloom of Yesterday is a lovely piece of creativity that deserved the trophy.

*****

Also captured with colour and splash but with a dash of melancholy was the Filipino entry, Die Beautiful, by Jun Robles Lana. The film has an uncanny resemblance to a Pedro Almodovar work. Bright colours, great characterisation and a tone of sensitivity made Die Beautiful look very similar to the Spanish master’s canvas. All about a transgender, called Patrick – who transforms himself into the lovely Trisha ( Paolo Ballesteros, who won the Best Actor Award) – the movie traces her character in a series of flashbacks after she collapses and dies as soon as she is crowned queen in a beauty pageant. Told with power and punch, the story of Trisha lets us glimpse into her life of extreme hardship – a life fraught with prejudice, with hurt, with sexual brutality and verbal abuse. Ballesteros brings fortitude and liveliness to the role.

*****

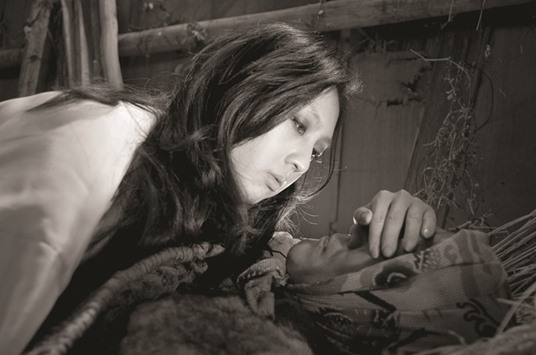

Japan is famous for fantasy and fable, and Snow Woman, is an eerie tale of a man who falls in love with a ghost responsible for the death of his guru. One of the legends which the Irish writer, Lafcadia Hearn, penned in his 19th century book of Japanese ghost stories titled, Kwaidan, Snow Woman has been filmed time and again, but most rivetingly by director Masaki Kobayashi. It is this surreal story that director Kiki Sugino brings to the screen in the latest interpretation.

The movie opens on a terrible night of snow and storm in a Japanese forest where the Snow Woman appears in startling white to kill the guru. “You are young, so I will spare you,” she tells the disciple, Minokichi, and disappears. A year later, he falls in love with a beauty, Yuki, marries her and has a daughter. Who exactly is Yuki? Sugino tries her best to keep us in the dark till the end, but does not quite succeed. She told a packed press conference at Tokyo soon after her screening: “When I first read it, I had lots of questions, especially about the ghost making love to a human, and producing a child and whose form is not clear in the story itself.”

*****

Kenji Yamauchi’s At the Terrace – another Japanese work – pulls us down to hard reality, and unfolds a story of rivalry and ribald at a terrace party in Tokyo where two women and five men, all sozzled up, play a devastating psychological game of cat and mouse. It all begins rather innocuously with one of the men flirting with the wife of another till the masks are blown away revealing an ugly, tainted humanity. Secret desires, jealousies and hatred are laid bare as the seven people argue and bicker throwing caution and humility and decency and decorum to the winds.

What was really fascinating about this work was the helmer’s ability – throughout the 90-minute run time – to keep our attention riveted on his characters as they striped each other’s veneer of respectability. There were several moments when one thought that the camera would step away from the terrace – where all the action takes place. But no, the camera remained on the terrace in what one thought was a spectacular narration of a very ordinary incident – of an after party that went wrong. A wonderful climax totally unpredictable seemed like a great desert.

*****

All said and done, Iranian cinema has managed to stay afloat despite rigid censorship laws and a ruling clergy not well disposed towards the arts, particularly cinema. And films from Iran have found a way of talking about the pressing issues of the day without offending the rulers. Mohsen Abdolvahab’s Being Born is an intimate narrative about a loving husband and wife.

While Pari acts in plays, her husband, Farhad, makes movies. They have a son, and are content with their lives till an unplanned pregnancy threatens to disrupt their peace and joy. Farhad wants the child to be aborted, but Pari is dead against killing any living being. And there is no meeting point, with Pari deciding to shift away from Tehran to her father’s house. “I do not want you to drag me to a clinic for an abortion,” she tells him.

What is amazing about the film is the director’s ability to tell a story that is fraught with angst and emotion with the least of melodrama. The couple, in spite of being angry with each other, is absolutely civil. There is no divorce, only a separation. “Many couples live apart and work out of different cities,” Pari tells Farhad, who is, of course, shaken. There is an extremely sorrowful scene at the end when we see the man shattered and miserable at the thought of having to live all by himself.

In a way, Being Born reminded me of another great Iranian movie, A Separation by Asghar Farhadi – where again a highly emotional marital problem is handled with subtle finesse. It was brilliance personified.

*****

Marco Dutra’s Brazilian work, The Silence of the Sky, is also a couple’s story, but one that is terrifying and arresting at the same time. It begins with a long rape, but captured with sensitiveness. We only see the wife’s contorted face as she is raped by two masked men in her own house. There is a glint of fear on her face, and a brief flash of a knife tells us why.

Shocking as it may seem, the husband returns home at that point and sees his wife being molested, but is so frozen with fear that by the time he gathers his wits to confront the rapists, they are gone. He chases them but they give him the slip.

What follows after this is a psychological play. The wife takes a shower and does not tell the husband about her trauma, and he, probably wracked by a deep sense of guilt at having been so helpless, keep mum as well.

The Silence of the Sky is pure arthouse fare with simmering traces of excellence in performance and photography. But the narrative is not always convincing: we never understand why the wife does not take her husband into confidence. Is the marriage fractured? Or is there so much self-loathing that she just cannot open up?

*Gautaman Bhaskaran covered the Tokyo International Film Festival, and may be e-mailed at [email protected]

A scene from Snow Woman.