Productivity is the main determinant of long-term living standards and its slowdown has been an issue for some time, pre-dating the global financial crisis and impacting a wide range of countries. Part of the problem is due to “statistical mis-measurement” issues, especially in relation to the difficulty of measuring quality improvements in services and the impact of new technologies.

“But part of the slowdown is real and may persist into the future,” QNB said. The decline in productivity growth implies slower global economic growth in the future. From a policy perspective, the persistence of productivity slowdown could mean a faster tightening of monetary policy, especially in the US, which is embarking on its own tightening cycle.

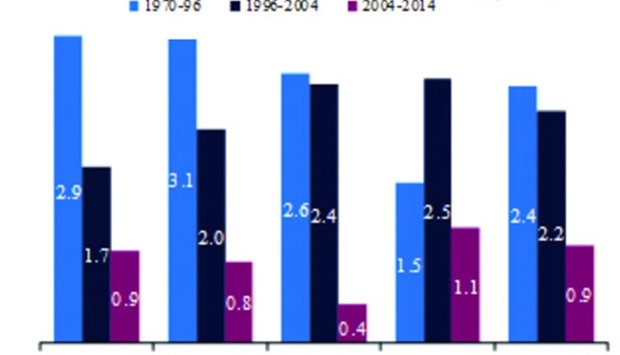

Productivity growth has been on a downward trend since the 1970s. In the US, it fell from an average annual growth of 2.5% over 1996-2004 to merely 1.1% in 2004-14.

More recently, productivity has disappointed even more, with its growth averaging merely 0.5% over the last three years. The problem is not confined to the US, but has also impacted most of the large economies.

Among the G7 countries, productivity growth has slowed from 2.4% in 1970-96 to only 0.9% in 2004-14.

There are three theories explaining this slowdown in productivity. The optimistic theory argues that the productivity slowdown is a result of increased statistical mis-measurement.

According to this theory, it is harder to measure productivity improvement in services than in manufacturing. The quality of service that comes with a meal at a restaurant is more difficult for national account statisticians to assess than the quality of cars produced in a factory.

And as the global economy shifts towards services and away from manufacturing, the mis-measurement problem can only get worse.

Similarly, as information technology and the Internet play a more important part of everyday life, the under-estimation of their impact could also lead to exaggerated estimates of the slowdown in productivity. It is hard to measure the value of the ubiquity of digital knowledge and entertainment, now available to almost everyone for free, QNB said.

The second theory acknowledges the mis-measurement problem, but argues that it cannot explain the full extent of the slowdown in productivity witnessed in recent decades. Part of the slowdown in productivity is real and the factors driving it could persist into the future.

These factors include the slowdown in global trade and increased protectionism, which has shielded less-productive firms from international competition. Another factor is slower investment growth, which has reduced the capital and machines available to each worker, leading to slower productivity gains.

Some argue that not only do we have a slower rate of investment, but that these investments are mis-allocated to less productive sectors such as real estate or finance, leading to an overall decline in productivity numbers.

The rise in unemployment following the global financial crisis might have added to the problem as the abundance of cheap- labour-led firms to switch from capital to labour and reduced the incentives to invest in productivity-enhancing technologies.

The third, and most pessimistic, theory on productivity growth argues that technological progress is over and that we have picked all the low-hanging fruit of major productivity gains. Holders of this view suggest that the in-house sewage system and aeroplanes are far more life-transforming than Twitter and YouTube. “But this view might be too pessimistic,” QNB said.

It typically takes decades for new technologies to be absorbed fully into everyday life and business. And it is not hard to imagine efficiency gains from online search engines, online booking platforms and the GPS system. And with technologies such as ride-sharing driverless cars seemingly around the corner, these could prove equally life transforming as the in-house sewage system or aeroplanes.

QNB thinks the second theory is the most plausible. It believes that part of the slowdown is due to statistical mis-measurement but part of the slowdown is real and could persist into the medium term, without being overly pessimistic about the long term. The productivity slowdown implies a lower rate of economic growth, especially when combined with declines in population growth.

In addition, a slower rate of productivity growth means that firms must hire more workers to meet rising demand, because it cannot make existing workers more productive. The resulting lower unemployment and tighter labour market typically leads to higher wages and inflation.

As a result, QNB noted the persistence of the productivity slowdown could result in higher steeper rises in interest rates than previously thought, an issue that the US may have to face soon.