By Anand Holla

Doha will have in its midst two monumental sculptures by maverick British sculptor and visual artist Marc Quinn — Frozen Wave, and The Origin of the World — as the Anima Gallery, The Pearl, prepares to roll out Quinn’s first solo exhibition in the region titled ‘Marc Quinn at Anima’ and featuring some of his finest sculptures and paintings.

The two awe-inspiring sculptures will be exhibited outdoors for the first time; one to be displayed in front of the Museum of Islamic Art, and the other outside the Anima Gallery. The exhibition opens on November 13 and will be on till February 13, 2017.

Iliana Kodzhamanova, Sales and Marketing Executive, Anima Gallery, told Community, “The Marc Quinn exhibition is questioning the continuous transformation and change of form or state over time… like the shell, represented in his sculptures, is changing its shape throughout the years.”

The ‘Frozen Wave’ sculptures are minimal arcs in stainless steel, including one measuring 7.5 metres long; their primal, gestural shapes originating from shells eroded by the endless action of the waves. Before they disappear and become sand, all conch shells end up in a similar form — an arch that looks like a wave, suggesting a self-portrait by nature. As for ‘The Origin of the World (Cassis Madagascariensis) Indian Ocean, 310’, Anima Gallery says, Quinn presents a realistic shell cast in bronze, three metres high. The title of the work refers to the emblematic painting by Gustave Courbet ‘L’Origine du Monde’, 1866, and invites the viewer to perceive the work as a monumental symbol of a woman’s sex.

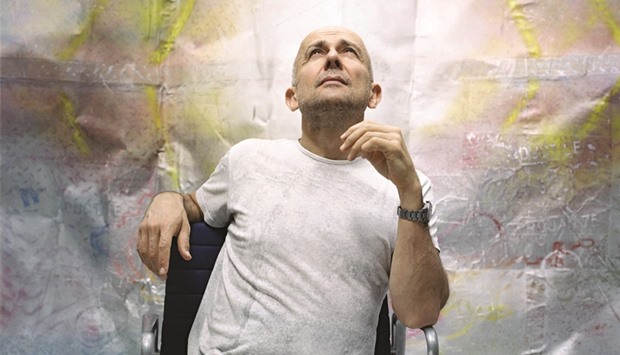

Born in London in 1964, Quinn graduated from Cambridge University with a degree in History and History of Art. He is one of the leading artists of his generation, with his sculptures, paintings and drawings exploring the relationship between art and science, the human body and the perception of beauty, among other things. Other key subjects include cycles of growth and evolution through topical issues such as genetics and the manipulation of DNA, as well as issues of life and death and identity. Quinn’s work uses a broad range of materials, both traditional and untraditional. The materiality of the object, in both its elemental composition and surface appearance, is at the heart of Quinn’s work.

It was in 1991 that Quinn came to prominence with his sculpture Self (1991), a cast of the artist’s head made from ten pints of his own frozen blood. “Other critically acclaimed works include Garden (2000), a full botanical garden frozen and displayed in Fondazione Prada, Milan; DNA Portrait of Sir John Sulston (2001), a genomic portrait of the genetic scientist Sir John Sulston, and Evolution (2005), ten sculptures depicting human embryos throughout the stages of its development,” says his biography.

“Major public installations include 1+1=3 (2002), a 20 metre artificial rainbow created for the Liverpool Biennale; Planet (2008), a monumental rendition of the artist’s son as a baby, permanently installed at The Gardens by The Bay Singapore; All of Nature Flows Through Us (2011), a ten meter bronze iris installed at Kistefos-Museet Norway; and Alison Lapper Pregnant (2005), a fifteen-ton marble statue of the heavily pregnant and disabled Alison Lapper, exhibited on the fourth plinth of London’s Trafalgar Square and later reinvented as a colossal inflatable sculpture, Breath (2012), for the 2012 Paralympics opening ceremony,” the bio adds.

Quinn’s perspectives on art and life are as fascinating as his work. In an interview with Tim Marlow about his exhibition The Sleep of Reason, Quinn explains why he finds ‘history painting’ interesting. “Traditionally, it’s considered to be the ‘highest’ genre, even higher than portrait or landscape painting,” Quinn says. “It’s evident if you look at the work of Rembrandt, for example. In 2011, during the London riots, it struck me that this was history being made. It made me think about how you create ‘history’ and how things are made from different threads. I thought about this first literally and then laterally, because I was looking at tapestries at the time, so I thought: why not make a tapestry and weave an image out of all these multiple threads?”

“The other thing that’s interesting about a tapestry is that it’s basically an analogue version of a pixelated image, because the tapestry is created from lots of points in the same way that a digital image is,” Quinn continues. “It’s like a medieval digital image. It is this kind of thinking, of linking the past to current methods of imaging, and using an ancient technical medium, which connects the work to history in some way. When they are placed on the floor, they become like flying carpets and there’s an element of fantasy. I like them equally as sculptures, or as carpets.”

Marc Quinn.