A meeting in Algiers at the end of September between Opec and Russia - which together pump more than half the world’s oil - has raised expectations that a deal could be struck to boost prices.

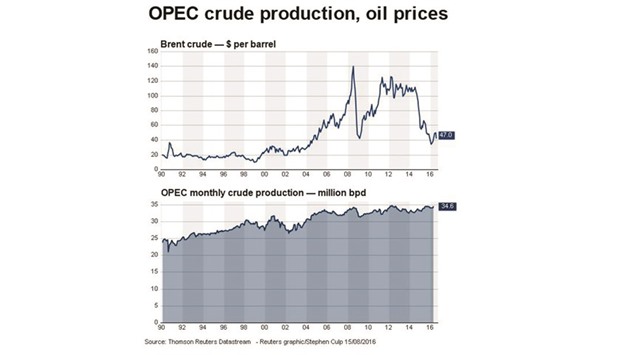

Oil is still trading at half its 2014 level amid a persistent global oversupply. While a production decline in the US has helped to curb the surplus and prices have risen more than 25% this year, swollen inventories across the globe have kept crude below $50 a barrel, too low for many producers to balance their budgets.

After two years of a Saudi-led strategy of all-out pumping, adopted to protect market share against the surge in US shale oil, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries and Russia are putting cooperation back on the table. Their last attempt to do this - a proposal to freeze output in April - collapsed as Saudi Arabia insisted Iran join the deal.

There may be four potential outcomes from the Algiers talks.

Production freeze

A freeze in production by Opec and Russia would be the most effective way of stabilising the market, Alexander Novak, the Russian energy minister, said in a joint press conference at the G-20 summit in China with his Saudi counterpart on September 5. Novak said his country is ready to cap output at the level of any month in the second half of this year, a period that so far has delivered record volumes from both Russia and Opec.

A freeze at July levels, the most recent month for which data is available, would mean Opec keeping production at 33.4mn bpd, roughly in line with demand for the group’s crude in the fourth quarter, according to data from the International Energy Agency.

The Paris-based adviser already expects Russia to hold output steady for the rest of this year and into 2017.

The major hurdle to freezing at current levels would be getting Nigeria, Libya and Iran on board, according to London-based consultant Capital Economics Ltd.

Those countries’ output has been severely constrained in recent years and they all hope to resume lost production. Political divisions have halted Libyan fields, Iran is still restoring exports halted by sanctions over its nuclear programme and armed groups have attacked Nigeria’s oil infrastructure.

“If they say a freeze at current levels, but making allowances for Iran, Nigeria and Libya, then you’re effectively freezing at a couple of million barrels above where you are today,” Thomas Pugh, commodities economist at Capital Economics, said by phone.

More barrels added

Iran is determined to raise production to 4mn bpd this year, from about 3.8mn currently, as it recovers market share after years of sanctions. Nigeria, which produced 1.44mn bpd last month according to data compiled by Bloomberg, is seeking to end the militant attacks and get back to the 2mn bpd it pumped in January. Libya is working to reopen its main export terminals, which could boost output to 1.2mn bpd by the end of the year, from about 300,000 a day currently. Iraq and Venezuela are also pumping less crude now than in January, so could seek a higher cap on their output.

Under this scenario, Opec could in theory get to pump as much as 36.2mn bpd by next year, about 2.7mn bpd more than the IEA’s estimate of demand for the group’s crude in 2017. That’s a bigger surplus than in 2015, a year in which oil prices dropped more than a third.

Production cut

Opec has on occasion overcome internal divisions and agreed to radical measures, most notably to slash production during the 2008 financial crisis.

Previous cuts worked because Saudi Arabia carried most of the burden, said Spencer Welch, director for oil markets and downstream at IHS Markit in London. Now the kingdom “has been quite clear that they are no longer willing to support prices on their own,” he said.

Since the oil slump began in 2014, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf producers have repeatedly resisted pressure from other members to cut production. Russia has pledged in the past to coordinate cuts with Opec, but that’s typically come to nothing.

Cuts are the most unlikely scenario, said Capital Economics’s Pugh. If they were to happen, it would have by far the biggest impact on the markets and “you would see prices surge,” he said.

Do nothing

The most likely scenario is that the talks don’t yield any curbs on output, said Pugh.

When that happened at the April freeze talks in Doha, prices slid right after the collapsed deal, but the impact was offset by an oil workers strike in Kuwait. The market continued to recover in the following months as wild fires shut down output in Canada and attacks in Nigeria cut production.

There may be some downside for Opec if it fails again to reach an agreement, said David Fyfe, head of market research and analysis at oil trader Gunvor Group Ltd. “At some stage it’s the law of diminishing returns, when you keep talking about a production agreement and not actually reach one,” he said.

FOUR