It’s 2009 and Brazil’s beloved President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva proclaims the nation’s biggest oil discovery its “passport to the future.” Rio de Janeiro is awarded the 2016 Olympics on top of the 2014 World Cup, and Brazilians see both as belated recognition of their rising international standing. The global financial crisis is a hiccup for effervescent Brazil as a commodity boom surges. Fast-forward to today and half of Brazilians, according to one poll, opposed hosting the Olympics with the economy in its biggest slump in a century. An investigation into corruption at the state-run oil colossus Petrobras, dubbed Carwash, has ensnared members of the business and political elite. Prosecutors have charged Lula, who denies any wrongdoing, with trying to obstruct the probe and with hiding assets from authorities. His protege and successor, Dilma Rousseff, has been suspended from office pending the outcome of an impeachment trial in the Senate. What went wrong? Can Brazil get its magic back?

The Situation

Among the embarrassing features of the Rio de Janeiro Olympics: Unfinished athlete housing and a trash-ridden sailing venue. Rousseff’s replacement, Vice President Michel Temer, has had some discomfiting moments as well. Within a month, three of his cabinet ministers were forced to step down over allegations related to the Carwash investigation, which they denied. Two of them were central to Temer’s plans to revive investor confidence and show the corruption probe would continue unimpeded.

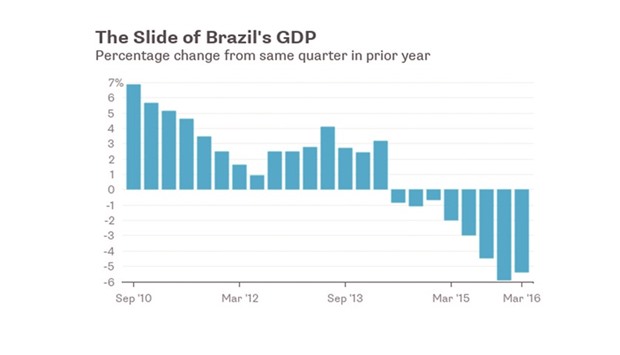

After a contraction of 3.8% last year, Brazil’s economy, Latin America’s largest, shrank again in the first quarter of 2016. The contraction of 0.3% from the previous quarter was smaller than forecast. Under Rousseff, Brazil’s credit rating was downgraded to junk. Business and consumer confidence levels fell to near-record levels. Rousseff, who denies wrongdoing, is charged with doctoring accounts to minimise the size of the budget deficit to improve her re-election prospects in 2014. A two-thirds majority vote in the Senate is necessary to remove her from office and ban her from any public post for eight years. If she’s found guilty, Temer would serve out her term, which ends in 2018.

The Background

Brazil has suffered boom-and-bust cycles and political instability since independence from Portugal in 1822. Half its 2015 exports were raw products, so its prosperity is sensitive to the vagaries of the commodities markets. On paper, Brazil looks like a powerhouse. It’s the fifth-largest country in the world, by land mass and population. Its offshore oil reserves include the Western Hemisphere’s biggest discovery since 1976. It has the second-largest iron ore reserves, is the second-largest producer of soybeans and third-largest of corn. On the other hand, its wealth distribution remains among the most unequal. Good times did provide cash to beef up the Bolsa Familia social welfare programme that became an international model for poverty eradication. The new middle class went shopping, boosting growth. Now, with commodity prices dropping and industry sputtering, that model appears to have run its course. Investment that would make the economy more efficient has remained well below half that of China as a percentage of GDP.

The Argument

Rousseff’s opponents argue that her time is over. They say she bungled management of the economy and note that Brazil’s benchmark stock market index and currency tend to rise when the news seems to favour her removal. Her critics maintain that even if she survives her trial, weak approval ratings and a fragmented governing coalition would make it difficult for her to accomplish anything meaningful through the end of her term. Rousseff’s supporters argue that her opponents are trying to invalidate their democratic choice. Rousseff herself accused Temer of attempting a coup. Rousseff’s defenders note that despite the massive Carwash probe, she has not been accused of graft, unlike many of the legislators who are deciding her fate.

Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics

BRAZIL