Admittedly even a master cannot make a masterpiece every time he dips his brush into paint to pat patterns on the canvas or every time he takes up a chisel to carve an image out of stone. A writer cannot do that as well every time he puts pen to paper. And so it is not strange that Neeraj Pandey has disappointed us with his latest yarn of a love story that gets caught in a web of extra-marital angst couched in administrative corruption and cunning.

Akshay Kumar’s latest outing as a Indian Navy Commander in Pandey-produced Rustom is certainly a let-down from his reasonably racy and gripping A Wednesday and Special 26 — which he helmed. Tinu Suresh Desai has directed Rustom.

The most important reason why Rustom slipped into a rut is perhaps Pandey’s over-confidence in assuming that he would be able to spin a story out an infamous murder that rocked what was then Bombay in 1959, deeply disturbing the city’s two most moneyed and hence influential communities, the Parsis and the Sindhis. Pandey and Desai would have been able to do this — who knows — with a degree of success had they stuck to the actual incident, without veering off it and adding layers. Perhaps they did this to bring the audiences around to empathise with the dashing and decorated Commander, who in the film is called Rustom Pavri.

But let us take a peek into the actual homicide. Kawas Manekshaw Nanavati, a Parsi, was an upright officer with middleclass values. His love for his English wife, Sylvia, and three children was beyond question, but his long absences from home when he was away at sea, appeared to have pushed the lonely wife (we saw this treated with beauty and dignity in Satyajit Ray’s Charulata) into the arms of a rich Sindhi playboy, Prem Ahuja. The ugliest part of all this was that Ahuja was a good friend of Nanavati, a fact that literally devastated the husband. When Nanavati returned to the shore on one occasion, Sylvia confessed to him her affair with Ahuja, and said she wanted a divorce.

An agitated Nanavati dropped his wife and children at the Metro cinema, and drove down to Ahuja’s office. Since he was not in, Nanavati went to Ahuja’s flat and found him emerging from his bath. “Will you marry my wife and take care of our children?” Nanavati asked Ahuja. “Do you expect me to wed every woman I go to bed with,” quipped Ahuja, sarcasm dripping from his words. An already enraged Nanavati was pushed to the precipice, and he fired three shots from his service revolver which he had collected earlier from his naval headquarters under some flimsy pretext.

The three shots shocked a newly independent India, prodding a salacious tabloid like Blitz, then edited by a renowned Parsi, R K Karanjia, to go on an overdrive with a vehement support for a fellow Parsi, Nanavati. Blitz’s circulation rose dramatical as did its cover price, and Karanjia in what was undoubtedly the first ever trial by the media (it is quite common today) turned not just public opinion in Nanavati’s favour, but also the decision of the nine-member jury, which pronounced 8 to 1 that the Commander was not guilty. The Parsis of Bombay — and even many other communities — saw Nanavati as a man wronged, a husband betrayed, while the Sindhis (a group to which Ahuja belonged) felt a sense of remorse and rancour. His sister, Maime, was furious.

The tension between the Parsis and the Sindhis was rising, and sensing the mood, the Sessions Court overruled the blatantly partisan jury’s verdict and convicted Nanavati to life imprisonment. The High Court and the Supreme Court went along with this ruling, and Nanavati spent three years in jail, a large part of this period, though, on parole and in hospital.

When public opinion urging the government to free Nanavati showed no sign of easing, the Maharashtra (Bombay was the capital of the State) Governor, Vijayalakshmi Pandit (then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister) thought of a way without offending either of the groups. A Sindhi trader, Bhai Pratap, was also serving time in prison for an economic offence, and Pandit worked out a quid pro qo after persuading Ahuja’s sister, Maime, to grant a pardon. Both Pratap and Nanavati walked out of prison the same day.

Nanavati and his family left for Canada soon after, and he died in 2003. Sylvia is still living in a suburb of Toronto.

Rustom adapts the basics of the real-life plot to key in a story where it is not so much the public outcry but the defence argument (conducted by the under-trial Rustom himself) that helps the court to set the murder accused free. Here the judge follows the jury’s decision — 8 to 1.

The movie often seems superfluous. I know people in the 1960s Bombay, especially the rich, dressed in a certain flamboyant fashion, but Rustom overdoes this part. Ileana D’Cruz, essaying Rustom’s wife, Cynthia (Sylvia in real life), is so garishly made up that it jars. Ditto Esha Gupta, who enacts the actual Maime as Priti Makhija in the film. Often seen with a cigarette, she comes off more like Mata Hari, scheming to get at Rustom. She hardly seems shattered by the murder of her brother, Vikram Makhija (Prem Ahuja, actually). Playing along with her is the public prosecutor, Lakshman Khangani (portrayed in the fictional account by Sachin Khedekar) — who appears so clownish that it seriously belittles the importance of this hugely respected judicial office. And Karanjia was no joker either as the film pictures him; Kumud Mishra plays this part as Erach Billimoria — who is often chastised by the judge (Anang Desai, who resembles a television serial actor that he is in any case) and thrown into a police lockup for a day.

If the director had wanted to get his audiences laughing with the exchanges between the judge and the editor, Billimoria, it appeared to be in poor taste, primarily because the grimness of the murder (both real and fictionalised) is undermined. The Nanavati case was no joke. It spelt the ruin of a distinguished naval career and the devastation of a happy family. And above all, the extra-marital affair was a breach of trust between a husband and his wife.

Rustom fails to highlight these with the kind of ernestness they deserve. Instead, the celluloid work glosses over these. Look at the scene where Rustom comes to know about his wife’s infidelity. He breaks a few photographs on the shelf and settles down with a drink. Somehow, Akshay Kumar’s Rustom Pavri fails to convey the pain and pathos of a man wronged and whose almost sacred trust is broken — as Commander Nanavati’s was.

It is true that Akshay is one of our better actors, but he still lacks the guts to physically disappear into a character. Okay, he tries looking like a disciplined naval commander, but he does not quite get there. There is a trace of artifice here, as there is in so many of the other characters — the only exception being Pawan Malhotra as the investigating officer, Vincent Lobo. He is splendid infusing his role with strictness as well as kindness. His stern face softens when he watches Cynthia — wracked by guilt. An admirable performance, indeed, by Malhotra.

Otherwise, Rustom when it does not drag, comes off as a hyped-up Bollywood work that relies on costumes and make-up and interventionist background score and stilted styles to present its case. In this case, a canvas of a lovely romance gone bloody sour.

(Gautaman Bhaskaran has been

writing on Indian and world cinema

for close to four decades, and may be e-mailed at [email protected])

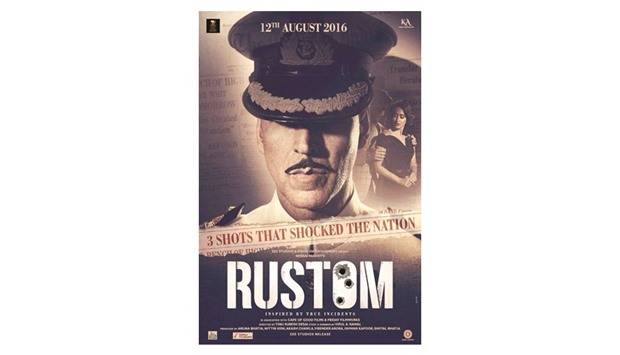

DISAPPOINTING: A poster for the film, which fails to do justice to its subject matter.