With the 31st Summer Olympics set to begin in a few days, here are a few athletes who captured our imagination back in the days with their remarkable feats.

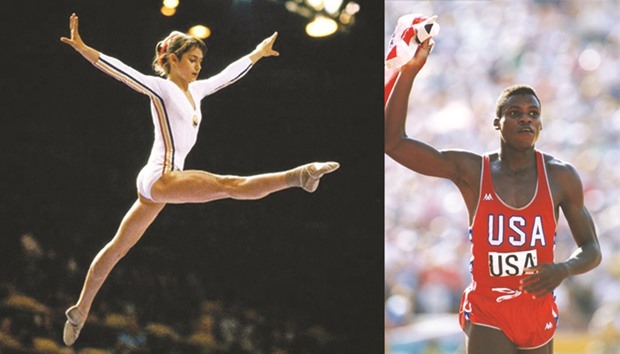

Nadia Comaneci

The perfect 10

Perfection is a rare commodity but 40 years ago in Montreal, Romanian gymnast Comaneci achieved it seven times, in the eyes of the judges, when she was just 14.

Belarussian Olga Korbut had paved the way for Comaneci’s success four years earlier in Munich, when her spectacular feats on the beam and uneven bars won her three gold medals, ignited gymnastics’ popularity and set off a fierce rivalry with the tiny Romanian.

The result was Comaneci, then only 4ft 11in (1.50m) tall, scoring the first ever perfect 10.00 scores — four times on the uneven bars, and three times on the beam, as she won gold in both events plus the all-round title.

Another two gold medals were to follow at the Moscow Games in 1980.

Fellow gymnasts detailed abuse and beatings at the hands of coach Bela Karolyi, and while under his care Comaneci was once rushed to hospital after reportedly drinking bleach.

Comaneci competed until 1981, and fled Romania just before the fall of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989.

She now lives in the United States, where her business interests include a gymnastics academy.

Greg Louganis

The greatest diver?

America’s Louganis dominated his sport in the 1980s when he won two gold medals at Los Angeles in 1984 and defended both titles at Seoul in 1988, despite famously smashing his head on the springboard.

Louganis may have finished his career with more Olympic titles if not for the USA boycott of the Moscow Games in 1980.

The enduring image of Louganis is when he painfully hit the back of his head during a reverse two-and-a-half somersault in pike in the preliminary rounds at Seoul — the stuff of nightmares for divers.

But after stitches, he recovered his composure to reach the final and then win the title, cementing burnishing his golden-boy image.

However, life had never been easy for Louganis, the adopted son of a Swedish-Samoan teenage couple who was bullied at school, abused by his business manager and found out he was HIV positive six months before the Seoul Games.

He came out publicly as gay in an Oprah Winfrey interview in 1995, prompting criticism in some quarters about the bloody head-injury incident in Seoul.

Edwin Moses

The man no one could beat

For nine years, nine months and nine days, nobody finished in front of Moses, who set four world records in the process. At the 1976 Montreal Olympics, his first international event, 20-year-old Moses won the 400m hurdles by eight metres, the largest margin of victory in the event’s history, also breaking the world record.

Moses missed the 1980 Games because of the US boycott, but won a second gold medal at the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984 and a bronze at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when he was 33.

When asked how he wanted to be remembered, Moses once said: “Hopefully, as the guy nobody could beat.” His final world record of 47.02sec was set in 1983 and was only broken by the current holder, Kevin Young, in 1992, when he ran 46.78 in the Barcelona Olympics final.

Daley Thompson

King of the decathletes

Thompson was a child at boarding school when his father was shot dead in an argument in the street, but he overcame the tragedy to become the most celebrated decathlete in history, winning two Olympic gold medals and setting four world records in his career.

The Briton, whose fierce competitive drive and irreverent attitude divided opinion, won his first Olympic title at the 1980 Moscow Games, which were overshadowed by Cold War tensions and were boycotted by the United States and West Germany.

But he won over the normally pro-Soviet Moscow crowd, who gave him a standing ovation at his victory ceremony.

Four years later in Los Angeles, Thompson had to dig deep in a hard-fought battle with Germany’s Jurgen Hingsen, the world record-holder, until strong performances in the discus, pole vault and javelin made him champion-elect before the final event, the 1,500m.

Thompson could afford to finish 11 seconds below his personal best and still break Hingsen’s decathlon world record, but instead he cantered down the final straight to finish a whisker too slow to set a new mark.

At the press conference, he wore a T-shirt emblazoned with the message, “Is the world’s 2nd greatest athlete gay?”, a provocative reference to rumours about Carl Lewis. He also made jokes about fathering a child with Princess Anne, another incident which created negative headlines in his hour of triumph.

Thompson’s athletic achievements are not in doubt: between 1979 and 1987, he was undefeated in all competitions, and he is the only decathlete to hold the world, Olympic, Commonwealth and European titles at the same time.”All I ever wanted to be was the best. I don’t enjoy fame,” he told the Independent in 2008.

Carl Lewis

The heir to Owens

Lewis stole the show at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, when he matched Jesse Owens’ achievement of winning four gold medals in the 100m, the 200m, the long jump and the 4x100m relay, in front of his home fans.

In 1988, Lewis gained a second gold medal in the 100m after Ben Johnson was disqualified for doping, and also defended his long jump title and picked up a silver in the 200m.

And in Barcelona in 1992, the American was a winner again as he anchored the 4x100m relay team to victory and picked up a third long jump gold medal, stunning world record-holder Mike Powell in the final.

Four years later, Lewis defended his long jump title for a fourth time, when as a 35-year-old underdog he summoned up one last golden leap to reach a career tally of nine Olympic titles.

He was named male athlete of the century by the IAAF in 1999, and sportsman of the century by the International Olympic Committee.

But despite his successes, Lewis’s aloof attitude rankled with rivals and spectators alike, puncturing his popularity.

Worse was to come when in 2003, it was revealed that he failed three drugs tests for small amounts of stimulants at the US Olympic trials before the 1988 Seoul Games, where Canada’s Johnson was vilified for doping. “The climate was different then,” Lewis said later. “Over the years a lot of people will sit around and debate that (the drug) does something. There really is no pure evidence to show that it does something. It does nothing.”

Nadia Comaneci, Carl Lewis