In the sad state of affairs following the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom, former “Remainers” – those who wished to stay in the EU – seem to have given up altogether on fighting for the future of their country. Worse still, many seem to have accepted the fundamental premise of the anti-EU “Leave” campaign: that there are too many Europeans in Britain.

This has changed the terms of the debate for the worse, and has led to hopelessly wishful thinking: Perhaps the UK won’t actually lose much market access if it imposes immigration restrictions on EU nationals.

Perhaps the EU itself will abandon free labour mobility in an attempt to appease the UK. Perhaps the EU will make special exceptions to protect the British university sector, or treat the UK like Liechtenstein, a microstate with access to the single market.

In fact, with Remainers accepting the argument that Britain should keep Europeans out, the UK – or at least England and Wales, if pro-EU Scotland and Northern Ireland leave – is headed for a “hard” Brexit, not just from the Union, but from Europe’s single market. If this happens, it will cost the country dearly.

The full extent of the fallout is unknown, but we can expect it to be painful for many people and damaging to many institutions.

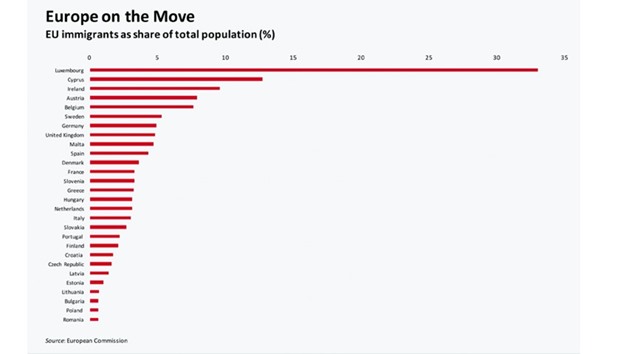

Is there any merit to the claim that the UK has become flooded with newcomers from other EU member states? The chart accompanying the article shows the percentage of EU immigrants in each EU country. The UK is at the upper end of the distribution, but it is on par with many other EU members, and it is far from having the most EU immigrants per capita.

In fact, the share of EU immigrants in the total population is twice as high in Ireland.

As British policymakers navigate the post-Brexit landscape, they should consider the Irish example, given the similarities between the two countries.

Ireland and the UK both have housing shortages, especially around metropolitan centres such as Dublin and London. And they both have public services that leave something to be desired – in fact, Ireland’s are much worse than Britain’s.

While the Irish are not British, they are closer culturally than other Europeans. As we saw in 2008, when Irish referendum voters refused to ratify the Treaty of Lisbon, there is a potential anti-immigrant voting bloc in the poorer parts of Dublin. These are the same kind of voters who turned out for the UK’s Brexit referendum – poorer people who have not felt the gains from globalisation.

The question, then, is why the Irish haven’t developed UK levels of animosity toward EU immigrants, especially given the appalling way in which the country was treated by European institutions in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

Surely, the British media bear considerable responsibility for the difference. Ireland has nothing like the mendacious, jingoistic gutter press that thrives in the UK.

Much of the blame, however, lies with British political leaders. One the one hand, there are those who have made careers out of attacking the EU, often on entirely specious grounds. On the other, there are lukewarm Remainers, such as former prime minister David Cameron, who never made a strong case for continued membership in the EU.

Now, even committed Remainers are failing to make the case for continued two-way labour mobility between the UK and the EU, and for membership in the European Economic Area (EEA).

Ireland hasn’t had this problem. Notably, Sinn Fein, Ireland’s nationalist party and the former political arm of the Irish Republican Army, has not indulged in the kind of xenophobic rhetoric used by the UK Independence Party.

In fact, to its immense credit, Sinn Fein has gone out of its way to adopt a progressive stance on the issue of immigration from the EU and elsewhere.

Many commentators have correctly pointed to the economic effects of globalisation to explain anti-immigrant sentiment. The fact that globalisation produces both winners and losers certainly explains much of the anti-globalisation backlash now apparent in the UK and elsewhere. But other things matter, too, such as cultural chauvinism.

Put plainly, English animosity toward the presence of fellow Europeans has a lot to do with some of the worst aspects of English society.

Addressing shortfalls in public services can help to mitigate economic concerns about immigration, and about globalisation more generally. Just as important, former Remainers must continue to explain to the English why the free exchange of goods, services, and people with Europe is good for Britain.

The UK voted to leave the EU, but Brexit comes in two flavours: membership in the EEA, with access to Europe’s single market and free movement of people, or an exit from the single market, followed by unpredictable trade negotiations.

There is still a huge amount to play for: we don’t know which of these two outcomes English voters would choose.

Unfortunately, it looks as though the UK is now headed for the second option – a “hard” Brexit – by default. For Remainers not to make the case for EEA membership, when they had previously been in favour of remaining in the EU, is an astonishing abdication of responsibility. - Project Syndicate

*Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke is professor of economic history and fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford.