The atmosphere was particularly festive around the Latin American players at baseball’s recent All-Star game.

A quick glance around confirmed their growing influence on America’s pastime.

One of their own, soon-retiring David Ortiz of the Boston Red Sox, received a hero’s farewell. Of the 79 players selected as All-Stars, 29 were born in Latin America.

So it came as a surprise to some of them to hear about the managerial landscape in the major leagues, specifically that not a single field manager is of Latin American descent.

“Not one?” Detroit Tigers first baseman Miguel Cabrera said.

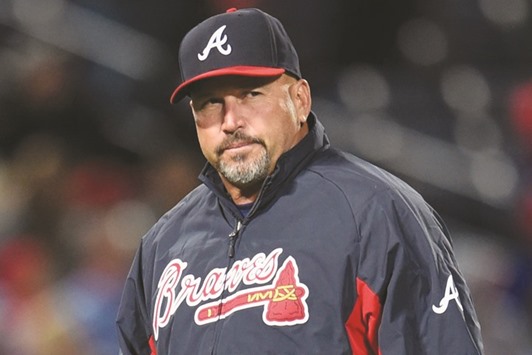

Fredi Gonzalez was the last. He was fired by the Atlanta Braves in May.

“Wow,” Cabrera said.

You know what’s funny? There’s one in Japan.

Cabrera opened his eyes wide. He looked around, leaned forward and whispered incredulously, “What the... “

He punctuated the sentence with an obscenity, cracked a smile and laughed. The people around him laughed, too.

How could they not? The situation borders on absurd.

No one is advocating that teams hire an unqualified candidate for the sake of diversifying the managerial ranks. It’s just hard to believe that not one of the 30 best managers in the world descends from a part of the world that produces about a quarter of major league players.

What about Sandy Alomar Jr.? Omar Vizquel or Eduardo Perez? Alex or Joey Cora?

A bilingual Latino manager would have clear advantages, namely that he would be able to better connect with a greater percentage of his players. Perez pointed to Mike Matheny’s success as manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. Matheny is white, but speaks Spanish. He also played in winter leagues in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

“He understands the culture,” said Perez, an ESPN analyst who has worked in the major leagues as a player, coach and front-office executive.

Players say this understanding is important, which is why their union has expressed concerns about the situation. There are only two minority managers: Dave Roberts of the Dodgers, who has a black father and Japanese mother; and Dusty Baker of the Washington Nationals, who is black. That number is down from a high of 10 in 2009.

“To be in a position where we don’t have those that reflect our membership in positions of leadership is disappointing,” said Tony Clark, executive director of the players association. The league shares the union’s concerns.

“The absence of a Latino manager is glaring,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said.

The problem is obvious. The causes and the solutions aren’t.

Multiple executives who have taken part in managerial searches said they couldn’t explain the trend.

Manfred speculated that it could be a blip.

“There are 30 jobs and 30 high-turnover jobs when you’re talking about field managers and you’re going to have an ebb and flow in terms of diversity,” Manfred said.

Nonetheless, Manfred said the league is making concerted efforts to remedy the problem, pointing to a rule implemented by his predecessor, Bud Selig, that requires tams to interview minorities for high-profile positions in baseball operations. The commissioner’s office has also hired a leadership search firm to prepare minority candidates for interviews and launched an initiative to stimulate greater diversity at the game’s administrative levels.

Even without encouragement from the league, individual teams understand the necessity of diversifying their coaching ranks. The majority of staffs now have Spanish speakers. The same is true in the minor leagues.

But some former and current Latino instructors are concerned they are viewed not as real coaches with baseball acumen, but instead as caretakers for the organization’s young Spanish-speaking players.

Others wonder if they are being excluded as a result of the game’s shift toward analytics, that perhaps front offices think they lack the educational background or intellect to employ statistically based strategies.

“To me, it comes down to ignorance” on the parts of front offices, said Perez, who played and studied at Florida State University.

Perez pointed to how Alex Cora was educated at the University of Miami and his brother Joey at Vanderbilt.

Edgar Gonzalez is hopeful his openness to analytics will provide with an edge over other bilingual candidates and land him a minor league position that could set him on the path to eventually manage in the major leagues. A former major league utilityman who was once a minor league instructor for the Chicago Cubs, Gonzalez studied marketing at San Diego State and described himself as mathematically inclined.

Gonzalez, the older brother of Dodgers first baseman Adrian Gonzalez, said he utilized analytics over the winter when he was the manager of the year in the Mexican league.

He understands the role of chance in all of this. He landed his position in Mexico because a book he wrote on baseball was read by the owner of a team. He knows he might need a similar break here.

Ortiz said the situation will change, if only for one reason.

“The racial barrier that existed in the past has been eliminated,” Ortiz said in Spanish.

That’s debatable, but Oritz was optimistic.

“There have been Latino managers in the past and I’m sure there will be more,” he said. “It’s a question of time.”

Fredi Gonzalez