Google Inc.’s latest technological marvels point to a future where you’ll never need to visit websites, write a term paper or stress over what to buy for your mother’s birthday.

For consumers seeking convenience and speed, it all sounds great. But how will any of it make Google money?

The Mountain View, California, company’s apparent transition from go-to search engine to omnipresent virtual assistant probably will require rethinking its advertising business.

By tracking Web browsing, emails, chats and more, Google has become a dominant force in digital ads. It mines that wealth of personal data to present ads to the people most likely to care about them. Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc., relied on that ad machine for about 88 percent of its $75 billion in revenue last year.

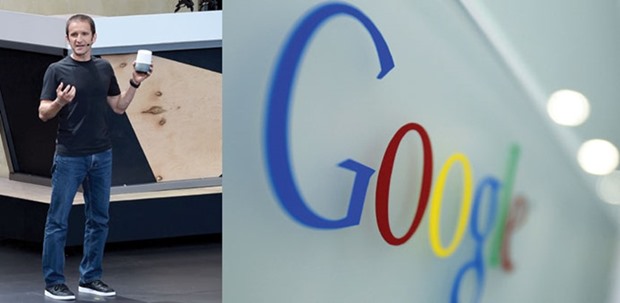

But most of the ads Google technology places across the Internet won’t make sense anymore if the types of products and apps the company announced recently at its annual I/O developer’s conference catch on. For instance, the small Google Home drum listens to spoken commands and responds with words of its own. Where does an ad with a link, a picture and two lines of text fit in? In general, Google wants to provide instant answers rather than having people peruse traditional search results, some of which are ads.

“The ad business isn’t going away any time soon, but they’re looking at all these new areas and as those products gain a larger user base, the question is how do you monetise those?” said Martin Utreras, senior forecasting analyst at ad industry research firm EMarketer.

Google declined to comment, but an individual familiar with the company’s thinking said there are no immediate plans for ads in the new products and apps.

The issue for Google goes beyond its new vision for search. People are spending increasing amounts of time using apps such as Snapchat and Facebook, which have turned that consumer attention into their own fast-growing advertising businesses. Facebook formalised ad-selling in 2006, about six years after Google, and now has about one-fourth the ad revenue of Google.

The apps represent a problem for Google because they’re, in many cases, assembling data about users that advertisers could find more interesting than what Google collects. In addition, some apps are presenting ads in a more creative fashion than what’s offered by Google. The presentations get around ad-blocking software and command high fees from advertisers.

Financial analysts say it’s too early for them to raise concerns about the rise of personal assistant gadgets and apps and Google’s move away from old-school search. For now, combined revenue from Google’s YouTube video app and the Play app store is more than making up for diminishing interest in traditional services. They also have confidence in Google coming up with answers.

“We continue to believe Google is investing smartly for the long-term and building competitive” barriers, RBC Capital Markets’ Mark Mahaney said in a report earlier this month.

But the unveiling of the forthcoming Home device and the chat apps Allo and Duo show that Google recognises it can’t let the likes of Amazon.com, Snapchat and Facebook go unchallenged.

The offerings are attempts “to build up their own services and attract as many, if not more, users than their competitors,” said Mark Hung, a vice president at research firm Gartner.

There are reasons to like them. Allo learns a user’s writing style and automatically suggests replies to messages. Home, whose price and release date weren’t disclosed, includes Google’s new assistant tool that will combine contextual clues like a user’s location and the time with multiple databases to present actionable information.

But amassing users is half the challenge. Shaping ads will be the other.

If someone asks Home to book a dinner table using OpenTable, should Google’s virtual assistant first run a brief audio ad for a different nearby fine-dining spot? If a user turns to Allo to chat with a bot developed by retailer Sephora to buy a new makeup set, can Google interject with a video ad for a new hair curler?

Or does Google forgo ads on Home and Allo and simply charge a fee to OpenTable or Sephora for bringing them business. Transaction revenue could be “a lot more lucrative” than standard ads, Hung noted. And where do competitors such as Yelp and Macy’s fit into the scenarios?

“With virtual assistants, we’re at where Web pages were in 1995,” said Omar Siddiqui, chief executive of chatbot development tool-maker Kiwi Inc. “Business models have yet to emerge.”

Another possibility would have Google extend its app store to third-party virtual assistant services. People browsing the app store could see Sephora’s shopping bot on the top of their smartphone screen because the company has paid for promotion.

But with Home, Google is “in the business of providing fast, accurate answers, so they are unlikely to interrupt the flow with an audio ad,” said Jason Hartley, vice president and search practice lead at ad agency 360i.

Google could come out ahead in the end because it gathers users’ personal preferences and desires as long as they are using its products. Advertisers will fork over more money when additional data lead to more efficient spending, Hartley said. Assuming Google can continue to place ads in other companies’ apps and draw people to its standard mobile searching tools, maintaining a steady business shouldn’t be a challenge.

What provides revenue growth is less clear. — Los Angeles Times/TNS

RINGING IN THE NEW: Google manager Mario Queiroz presents the interconnected loudspeaker Google Home during the opening of the Google developer conference I/O earlier this month in Mountain View, California.