A special court will tomorrow hand down the verdict in the landmark war crimes trial of former Chadian dictator Hissene Habre, with prosecutors hoping for a life sentence.

Habre, 73, was president of the central African country from 1982-1990, during which time he is alleged to have committed crimes against humanity and torture, with thousands of victims.

He went on trial last July in the Extraordinary African Chambers (CAE), established in Dakar by the African Union under a deal with Senegal.

Special prosecutor Mbacke Fall said the “apparatus of repression began to operate under the direction of Hissene Habre,” in closing arguments in February during which he called for a maximum life sentence.

Led by a judge from Burkina Faso, the historic case is the first time that an African leader accused of serious abuse of power has been tried by another country on the continent.

Often dressed in combat fatigues complementing his “desert fighter” nickname, Habre fled to Senegal after he was ousted in 1990 by Chad’s current President Idriss Deby.

Habre has declined to address the court and refuses to recognise its authority.

Neither he nor his legal team will be in court for tomorrow’s hearing, they confirmed to AFP over the weekend.

His court-appointed lawyers will attend the hearing and are hoping for an acquittal.”We have developed our arguments sufficiently well to prove that Hissene Habre is innocent,” said Senegalese lawyer Mbeye Sene.

“If the law is correctly applied, we will go straight to an acquittal for Mr Habre,” added Sene.

Investigators found that at least 40,000 people were killed during his rule, which was marked by fierce repression of opponents and the targeting of rival ethnic groups.

Witnesses have recounted the horror of life in Chad’s prisons, describing in graphic detail the abusive and often deadly punishments inflicted by the Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS), Habre’s feared secret police.

Victims were subject to electric shocks and waterboarding while some had gas sprayed into their eyes or spice rubbed into their genitals, the court heard.

Massa Moire, who was detained by the DDS for three years, was released in 1990.

“I still don’t know the reason for my arrest. My wish would be to see Habre sentenced to death. He brought so much pain to so many families,” he said, speaking at the headquarters of a victims’ association in Chad’s capital, N’Djamena.

Habre’s defence team has sought to cast doubt on the prosecution argument that their client was an all-knowing, all-powerful head of the DDS, suggesting he may have been unaware of abuses on the ground.

The former dictator lived freely for more than 20 years in an upmarket Dakar suburb with his wife and children, swapping his military garb for billowing white robes and a cap.

The African Union asked Senegal to try Habre in July 2006, but the country delayed the process for years under former president Abdoulaye Wade, despite an agreement to create the special court.

If convicted, Habre can expect a sentence of between 30 years and life with hard labour, that will be served in Senegal or another African Union country.

“It took 25 years of relentless campaigning by Hissene Habre’s victims to make this trial happen,” said Reed Brody, a lawyer for Human Rights Watch who has worked since 1999 to bring the case to court.

“The Hissene Habre trial is a watershed in the fight for accountability for the world’s worst crimes,” he added, in a statement released last week.

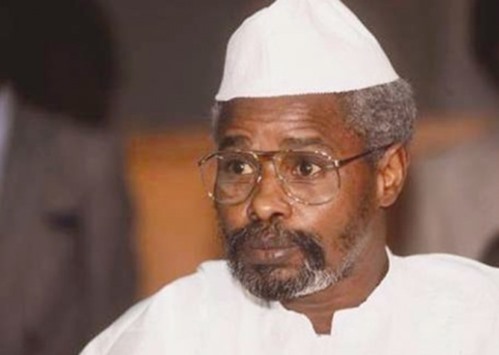

Habre ... facing justice.