Leukaemia patients out of options and given just months to live have achieved sustained remissions thanks to a new twist on cancer immunotherapy, according to a highly anticipated study from scientists at Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Experts at Fred Hutchinson refined an experimental technique that genetically modifies patients’ own cells to attack blood cancer, resulting in 27 out of 29 patients having no detectable signs of disease, the study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation reported. It’s the latest advance in what’s widely regarded as a potential new pillar of cancer care.

“We are extremely happy that we are beginning to figure out some of the nuances of this treatment,” said Dr. David Maloney, the oncologist and immunotherapy expert who was the study’s principal investigator.

Kristin Kleinhofer, 41, of San Jose, California, was one of the 27 patients who remained in remission. Her B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, or ALL, was halted 16 months ago after the pioneering Fred Hutchinson technique that targets two subsets of patient T-cells, a type of immune cell, to go after the cancer.

“They told me from the get-go that obviously there weren’t many options,” said Kleinhofer, who was first diagnosed with ALL in 2010. She was treated with chemotherapy and achieved remission in 2012 — but relapsed in 2014.

She was accepted into the Fred Hutchinson clinical trial that began in 2013 and received cancer immunotherapy treatment in Seattle on November 19, 2014. She was pronounced cancer-free less than a month later.

“All of these treatments have worked to date. I have so much respect for the doctors I had,” Kleinhofer said. “The good news is, I’m still in remission.”

The peer-reviewed study confirms findings informally reported in February, when Dr Stan Riddell, a Fred Hutchinson immunotherapy expert and oncologist, mentioned them at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, triggering a firestorm of response.

Headlines in some US and international media outlets proclaimed new hope for a “lasting cure” that could “wipe out cancer.”

But Maloney cautioned against hyping the results, which are very promising, but nowhere near a cure.

“People have to understand that the word ‘cure’ can only be used in retrospect,” Maloney said. “You can’t say anybody is cured until 10 years or some time has gone by.”

Still, the study includes the largest reported series of adult B-cell ALL patients treated with genetically engineered T-cells called CD19 CAR-T cells.

“The rates of remission in patients who had no other options have been astoundingly high,” Maloney said.

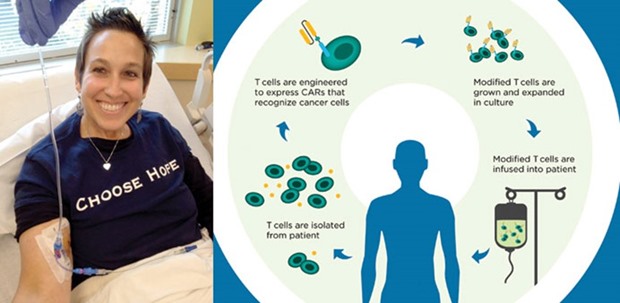

The technique works by removing millions of T-cells from patients and then using a disabled virus to introduce new genetic material in the form of antibody-like proteins called CARs, or chimeric antigen receptors.

The re-engineered cells are designed to target a protein on the surface of malignant B-cells known as CD19. When they’re reintroduced to the patient, they bind to the B-cells, destroying them — and the cancer.

This study was the first to show that instead of using all of the T-cells collected from patients, researchers could use two subtypes, called CD4 cells and CD8 cells, to create a stronger, longer-lasting remission. The CD4 cells are known as “helper cells,” which boost the immune response. CD8 cells are “killer cells” that attack the cancer, Maloney explained.

“You get more predictable activity in terms of anti-tumour activity” using the subtypes, he said.

The researchers also gained new insight into treatment of a potentially fatal side effect of T-cell therapy known as “cytokine release syndrome.” It occurs when the natural chemicals associated with immune response flood the system, resulting in high fevers, chills and other symptoms.

Kleinhofer was fortunate. She had to be hospitalised for nearly a week after her T-cell transplant with cytokine release syndrome, but it was merely miserable, not life-threatening, she said.

Researchers found that by modifying the dose of the genetically engineered T-cells, they could reduce the toxic side effects, Maloney said.

“We found that how sick people got was correlated with how much tumour they had,” he said. So they explored giving fewer T-cells to patients with more tumour cells.

The study is the latest to demonstrate the promise of cancer immunotherapy, said Dr. Rebecca Gardner, a paediatric oncologist at Seattle Children’s hospital who has conducted clinical trials of T-cell therapy in children.

“These results are at the top of the heap for what they are able to do in terms of medical responses,” said Gardner, who was not involved in the Fred Hutchinson research. “This is adding to the idea that, ultimately, we can use immunotherapy as a cure. But are we there yet? No.”

For Kleinhofer, getting past the cancer was only one hurdle. She received a double transplant of umbilical-cord blood in 2015 to rebuild her immune system, but then contracted infections that led to a condition that left her paralysed for months. Slowly, she’s learning to walk again and to rebuild her life.

“My whole journey, it’s been just like that,” Kleinhofer said. “You take it day by day. We’ve just accepted the battle, and we just move forward.” —The Seattle Times/TNS

u201cAll of these treatments have worked to date. I have so much respect for the doctors I had,u201d says Kristin Kleinhofer, 41, one of the 27 patients who remained in remission. u201cThe good news is, I’m still in remissionu201d