Even before most major news outlets confirmed that Prince had died, mournful posts began filling my timeline. First, there was denial: “No. No. No,” a friend tweeted. “Not Prince, not Prince,” wrote another. The other stages of grief soon followed.

I scrolled past concert memories on Facebook. Instagram was full of stills from “Purple Rain” and, later, photos of Los Angeles City Hall, Niagara Falls and the Eiffel Tower lit purple.

Prince’s actual funeral was attended by just 20 close friends and family members. Online, millions of us mourned together.

The outpouring was sincere but also eerily familiar. Prince’s death was a replay of David Bowie’s in January, with echoes of the public mourning for the victims of the November terrorist attacks in Paris.

Have we made an unspoken pact? When a death is newsworthy, we must grieve collectively now.

Because of social media, everyday people feel pressure to grapple with questions of etiquette that, in previous decades, only celebrities in the public eye - and subject to public criticism for perceived insensitivity - had to address.

If you’ve never travelled to Paris, is it necessary to denounce terrorism there? Is it enough to acknowledge the death of a well-known artist – R I P, Prince - or must you put together a heartfelt tribute?

In fact, no one would take offence if some of us decided to skip a round of grieving - if we decided not to change our avatars in memoriam. Probably no one would even notice. But perhaps that’s beside the point.

“Thinking about how we mourn artists we’ve never met,” tweeted one woman after David Bowie died. “We don’t cry because we knew them, we cry because they helped us know ourselves.”

In that vein, we seize upon celebrity deaths as yet another opportunity to express ourselves. The Fox sketch comedy show Party Over Here recently mocked online celebrity-death tributes as little more than self-congratulatory posturing. “Let us celebrate Jackie,” says comedian Alison Rich, in a skit that supposes Jackie Chan has died, “but let us also remember to celebrate me.”

Brief exclamations of sorrow often precede lengthy remembrances. We tell our followers how listening to a deceased artist’s lesser-known albums helped us survive high school, or just a rough night in high school.

We expect and accept this routine, which seems more meaningful than simply saying: “I was a fan.”

But we also have standards. While grieving publicly, we feel we must avoid the appearance of self-promotion at all costs.

Corporate marketers have learned this the hard way. After Prince’s death, the official Cheerios account tweeted a purple background with the words, “Rest in Peace” on top. The “i” was dotted with a Cheerio, and the hashtag was #prince. Mourning fans were outraged by the opportunism of the tweet, which was soon taken down.

There was a similar incident involving Hamburger Helper.

Collective grief can be a balm. But sometimes weighing in feels more performative than personal. We need to reclaim the option of saying nothing at all - to disconnect the association between remaining silent and not caring.

We don’t expect constant digital updates from someone who has recently lost a loved one, nor should we expect such missives from each other after a headline-grabbing tragedy or celebrity death.

We should grant ourselves permission to stay out of the public mourning ritual, whether because we’re not personally affected, or because we are affected so deeply we cannot immediately translate our grief to words. There is also comfort in silence.

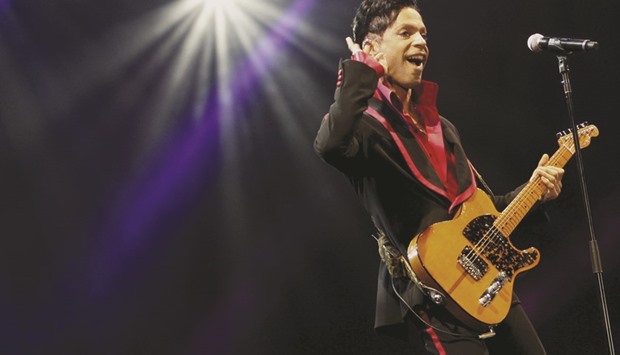

Flashback to 2010: US musician Prince performing on stage at Yas Arena in Yas Island, Abu Dhabi, on November 14, 2010.