These days, Bollywood is rolling into reality, perhaps having done to death pure fiction that often seemed forced and foolish.

In recent times, we saw Meghna’s Gulzar’s Talvar, about the horrific murder of a teenage girl in Noida, next to Delhi, and horror of horrors, her parents have been convicted of the crime. We also saw Ram Madhvani’s Neerja, the tale of a young valiant Indian Pan Am stewardess who laid down her life to help passengers flee from hijackers at Karachi airport in 1986. Then there was also Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh, the tragic incident of a Marathi language university professor who committed suicide after being shamed and humiliated for his homosexuality.

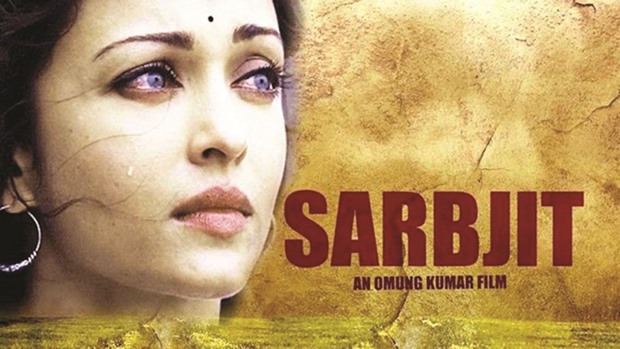

But probably, the upcoming Aishwarya Rai-Randeep Hooda-starrer from the Bollywood basket, Sarbjit, a biopic helmed by Omung Kumar, will rattle cinema — and on both sides of the Indo-Pak border.

Sarbjit Singh was a poor farmer in India’s northwestern state of Punjab who in his drunken stupor one night in August 1990 strayed into Pakistan through a unfenced border. He was initially mistaken for a spy, jailed by the Pakistani army, sentenced to death and kept in solitary confinement for long periods during his 23-years of incarceration.

Sarbjit was first charged with being spy, but later he was held guilty of the four bomb blasts in Pakistan’s Faisalabad and Lahore in early 1990 that left 14 bystanders dead.

Twenty-three years later in April 2013, Sarbjit was murdered by fellow prisoners in Lahore jail. It is widely believed that a plan was hatched by the prison authorities along with six inmates to kill Sarbjit. He was badly wounded in the deadly onslaught and died in a Lahore hospital a few days later.

Why was he done to death? It is averred that this was a revenge killing for the February 2013 execution in India of Pakistani extremist Afzal Guru for his role in the New Delhi Parliament attack in 2001. Had the operation gone as planned, most top Indian leaders — present in a Parliament session that day — would have died. The nation could have been left bereft of leadership, indeed a terrifying scenario.

Guru’s execution was highly unethical in one respect. Apart from the fact that capital punishment is now being viewed by most countries as barbaric, Guru was not allowed to meet his family for the one last time before the noose tightened around his neck. The hanging was carried out in a hush-hush manner — raising questions of legal impropriety as well.

But Sarbjit need not have been murdered. For, he was neither a spy nor a terrorist, and his was a case of mistaken identity that Islamabad refused to accept, pressured as it was into doing so by several hardline religious groups.

Pakistan said that Sarbjit was Manjit Singh — who was actually a Sikh terrorist caught later in Canada.

In 2008, Islamabad postponed Sarbjit’s execution indefinitely. Four years later in 2012, when Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari commuted Sarbjit’s sentence to life term, it was found that the poor man had already spent 22 years behind bars. A life sentence runs for a mere 14 years according to Pakistani law.

So, the administration announced Sarbjit’s release, which led to massive demonstrations in Pakistan by radical Islamic groups, such as Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamaat-ud-Da’wah.

Islamabad was once again under pressure and fearing further backlash retracted its statement to say that the prisoner to be freed would be Surjeet Singh, not Sarbjit Singh. His sister, Dalbir Kaur, who had spent her whole life fighting for her brother’s release called this “a cruel joke”.

For 20 years, Dalbir had fought a lonely but valiant battle to free her brother, who was much younger to her and was more like a son. A former school teacher, she said on innumerable occasions, “I will not lose hope and will not rest till I see my little brother out of jail.”

Dalbir is reported to have called India’s former prime minister, Narasimha Rao, a hundred times before he agreed for a one-to-one meeting with her.

The meeting eventually helped Dalbir, though much later, to secure a rare permission to visit her brother in the Lahore prison. There “I promised him that we will get him out soon,” she later told a BBC interview. She described how her brother couldn’t hold back his tears in his tiny cell as his sister tied a “rakhi” (an armband which a sister ties on her brother’s wrist, a symbolic gesture of love) to his wrist, reassuring him in every way she could.

Dalbir pushed the boundaries most relentlessly, refusing to take no for an answer. More than one million kilometres, two decades and a wide array of candlelight vigils and public rallies — Dalbir is credited with all these.

Former cricketer Navjot Singh Sidhu said in praise of Dalbir: “Every man should have a sister like her. She soaks the unimaginable pressures on her entire family like a sponge and comes out a winner”.

A member of India’s Parliament once quipped that “Dalbir exuded a kind of bold spirit that was typical of the state of Punjab” — whose people are known for their valour and courage of conviction.

In director Kumar’s (who in 2014 gave us a gripping Bollywood biopic, Mary Kom, a boxer from north-eastern India) cinematic sketch of Sarbjit, Aishwarya Rai — shorn of the glamorous image the former Miss World has always carried — portrays the simple, but fiery Dalbir.

Rai did not meet Dalbir before the shoot, but later had a very emotional conversation with Sarbjit’s heartbroken sister.

Actor Randeep Hooda who transforms into the lean and impoverished looking Sarbjit on screen said that “the biopic affected me tremendously and people around me thought that I was “ass”...“Everybody thought I was an ass… everybody around me just had enough of me… it somewhere has affected me. There is a certain sense of gloom that has come about since this movie”. Hooda was speaking at the film’s trailer launch.

“I have to keep telling myself, that ‘look, you did not go through 23 years of your life in prison, you did not go through all that hardship, you did not go through solitary confinement’, that is something that I have to keep reminding myself,” he added.

Hooda also said that the first time he heard the movie was being made was when “somebody forwarded me an article when the real Dalbir Kaur was saying that she would like me to play the role, and I was like ‘Really!’. I then did research and by the time I met Omung, I knew Sarbjit very well”.

Hooda lost an enormous amount of weight to look Sarbjit. He also started learning Punjabi and got a tooth mould from Canada, to show Sarbjit’s decayed teeth.

The celluloid work, Sarbjit, will hit the theatres mid-May, and appears like one good example of an earnest Bollywood attempt to shake off its oft-ridiculed image of being a song-and-dance tamasha.

Nil Bhattey Sannata

Ashwini Iyer Tiwari’s debut feature, Nil Bhattey Sannata (Good for Nothing/The New Classmate) — which premiered at the Silk International Film Festival in China’s Fuzhou late last year and which opened in Indian theatres on April 22 — is a powerful and honest work, completely shorn of the kind of pretension one sees in a large number of Bollywood movies.

Swara Bhaskar (who won the Best Actress Award at Fuzhou and whose roles in Tanu Weds Manu and Tanu Weds Manu Returns have been lauded) plays the illiterate maid, Chanda, in Nil Bhattey Sannata. Nursing a dream to educate her 15-year-old daughter, Apeksha (Ria Shukla), into a doctor, Chanda is often frustrated at the girl’s attitude. “A maid’s daughter can only hope to be a maid, like a driver’s son can only become a driver himself”, Apeksha repeats this ever so often with a kind of finality that depresses Chanda and demeans own her self-respect.

Almost on the verge of giving up on a teenager, who bunks school and can never seem to have a grip over mathematics, Chanda finds an epitome of benevolence in her employer, essayed with superb ease and finesse by Ratna Pathak Shah (Naseeruddin Shah’s wife). She understands the angst of a mother, and moots a plan to fulfil Chanda’s dream.

There are some wittily poignant moments in the film — like the one when Chanda is taken to meet the headmaster of Ria’s school (another riveting performance by Pankaj Tripathi), who has a start when he learns that the mother wants to join the institution and study along with her daughter.

Nil Bhattey Sannata is not just a touching story of a mother and a rebellious teenage daughter — who finds Chanda’s menial job as a house maid a kind of benchmark for her own ambitions — but also a great chapter on the importance of school education. Above all, the movie tells us that a parent’s handicap or limitation need not be a stopper for a child’s growth and progress.

Bhaskar portraying Chanda affirms this with rare power and fantastic simplicity — a yawning difference from the parts she played as a modern woman in the Tanu Weds Manu series. As is often believed by cinema greats, an actor must be able to let go his/her own self and sink into a character. Bhaskar does this with engaging precision.

*Gautaman Bhaskaran has been

writing on Indian and world cinema

for over three decades and may be

e-mailed at [email protected]

A poster for Sarbjit.