Maneesh Sharma’s tries hard in his latest work, Fan, to tell us that star worship can be suicidal. And coincidentally, Fan opened in India on April 15 at the same time when fans of Tamil actor Vijay were celebrating the release of his latest, Theri, by beating drums outside theatres, garlanding huge wooden cut-outs of the star and anointing them with sandal paste.

In an important way, Sharma’s work is a warning to all those who feel a crazy sense of attachment to their favourite screen heroes and heroines. Some fans stalk them and send messages of love dipped in desperation. Others want to meet actors in flesh and blood, and one of them in Fan is Gaurav Chadda (played by Shahrukh Khan) — a young man who runs a cyber cafe in Delhi, but spends all his free time mimicking his cinema hero, Aryan Khanna (also essayed by Khan), dressing up like him and even speaking like him. Helping Chadda is his uncanny resemblance to Khanna.

When Chadda wins a look-alike competition, organised by the community where he lives with his parents, he plans to meet Khanna (who lives in Mumbai) with his trophy. Chadda is so obsessed with Khanna that he travels ticketless like the star once did, and stays at the same hotel and in the same room the actor did in his early struggling days of moviedom.

However, when Chadda fails in his attempts to meet Khanna, the man from Delhi tries something foolish to grab the star’s attention. Sadly, Khanna reciprocates by pushing Chadda into jail for a couple of days.

A shattered Chadda vows revenge. And Fan takes us to Italy and England on a hit-and-chase run in which Chadda, dressed like Khanna, wrecks the star’s image and credibility by committing crimes. Chadda takes a young woman hostage at Madame Tussauds in London, and gropes a socialite in an Italian villa party, and everybody presumes that the villain is Khanna.

Though Fan has an important message for all those fans obsessively in love with stars, Sharma’s script is not only highly improbable but also plain idiotic. The kind of acts that Chadda resorts to in order to first attract Khanna’s attention, and later to destroy him are next to impossible — unless one is a Phantom or a Superman. Chadda is a mere mortal from a very modest family, who transforms himself into the star to fool cops and security guys at will. A good idea has been thus demolished through a lazy script.

As the noted Indian auteur who makes cinema in his native Kannada, Girish Kasaravalli, said during a discussion in Chennai the other day, writers and directors give authenticity and realism a go-by in order to make a point.

Sharma has done precisely that. He wanted to tell us that obsessive star worship is nothing but destruction and death. But he has made precious little effort to narrate the story with any sense of rooted realism. Surely, no man can hope to break into a superstar’s cordon of defence through the kind of tricks which Chadda adopts. They seem at best juvenile, and, worse, appear like a do-or-die attempt by Sharma to put Fan together.

Finally, Shahrukh Khan is no actor, for in film after film, he seems most reluctant to let go his own persona, his own mannerisms and just about everything else that stop him from being the character he ought to be in the first place.

Theri

When I walk into a Vijay film, I know exactly what I would be pounded with. Cyclonic action, humungous heroism, nobility and syrupy romance. Vijay’s latest Robinhood adventure, Theri, has all of these ingredients to make the movie into a masala that Indian cinema terms entertainment. In the first hour of the film’s run time of 158 minutes, I counted five songs and dances — one of them with Vijay (playing Indian Police Service Officer, Vijay Kumar) and his lady love, Mithra (a Bengali name that Samantha sports), dressed in Arabian costumes! A curious case of imagination running wilder than the movie’s make-believe creation.

When Vijay is not swaying to the beat of the drums and the hum of the musical notes, he plays Mr Noble in Khaki, bumping off a powerful minister’s (Mahendran in his debut role, and what a fine piece of acting from a man who once directed classics like Uthiripookal and Nenjathai Killathey) son, because he molested and murdered a young Information Technology professional.

A shaken and shattered minister vows revenge which, as he says in his viciously terrifying voice, will be worse than death. Yes, death to Vijay’s wife — Mithra had by then married the cop — and his fun-loving mother, portrayed in her characteristic style by Radhika Sarathakumar. The couple’s daughter survives the bloody onslaught in a kind of incident that reminded me of Sholay and Gabbar Singh’s evil demolition of a happy family.

All this in Theri comes to us in a sequence of flashbacks, and the Tamil work’s opening shots are in Kerala, where Vijay in an assumed identity as Jacob Kuruvilla is playing papa, papa to his little daughter, Nivi (Baby Nainika, a brat whose smartness goes beyond cinematic liberty).

And Nivi’s teacher is Annie (Amy Jackson, in her usual wooden avatar, looking positively uncomfortable lisping Malayalam) who flips for Jacob and lets her inquisitiveness get the better of her. She finds out about Jacob’s past, but director Atlee keeps an important part of the man’s mysterious life for the final frame.

Beyond this, there is little novelty in a plot that only appears rehashed (probably for the enth time) with some annoying and ethically questionable police methodology. In this day and age, are we to go home after watching Theri thinking that all that Vijay Kumar does in the movie is virtuous? Given the kind of the fan craze one saw at the opening of the movie — which contrary to a couple of Vijay’s earlier films — happened without any political interference, thanks to the upcoming elections in Tamil Nadu, cinema must introspect on the kind of social message it spreads.

However, to be fair to Atlee and his Theri, I must say that he got Vijay into a rare emotional mould. The star actually cried and emoted a great deal more than what he usually does. He has always had this tendency to mask his feelings with a cold, inexpressive face. This time, Vijay seemed delightfully human, essaying a very different kind of policeman, whose heart beats could be seen on his face.

* Gautaman Bhaskaran has been

writing on Indian and world cinema for more than three decades, and may be

e-mailed at [email protected]

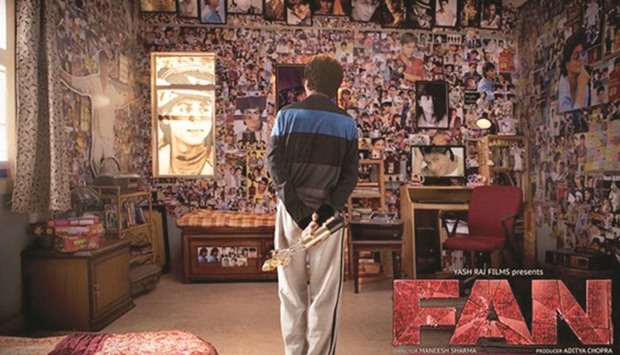

A poster for Fan. The film is let down by a weak script.