Diversifying public revenue and containing expenditure will keep deficits and debt ratios low in the GCC countries, and will contribute to the region’s high credit ratings and low funding costs, Asiya Investments has said in a report.

“Avoiding reforms will lead to high indebtedness or fast liquidation of state assets, and lower credit worthiness,” Jordi Rof, economist at Asiya Investments, said.

Gulf nations, he said, has only a “limited control” over oil prices, but they do have “some degree of freedom” for implementing necessary reforms and guaranteeing the sustainability of their public expenditure in the years to come.

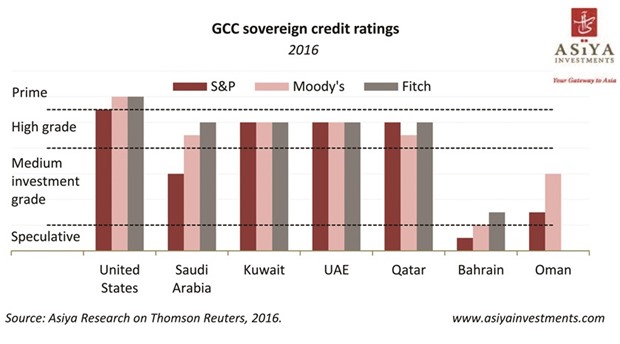

“Most rating agencies already expressed concerns about the impact of low oil prices on the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council). These concerns translated into downgrades and review announcements of credit scores, affecting both corporate and sovereign debt issuers,” Rof said.

For instance, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) lowered the ratings of several oil producers in February, including Saudi Arabia, Oman and Bahrain.

Moody’s also placed government bonds from Qatar, Saudi and the UEA on review for downgrade, along with several other issuers such as public companies and banks. The decline in oil prices has been the trigger of these revisions, but doubts about the capacity of GCC countries to implement the necessary reforms to balance their budgets are at the heart of the latest developments.

Credit scores show that Bahrain and Oman are in a “worse” position than other GCC countries. The differences are mainly due to reserve levels and the impact of lower oil prices on public finance.

As an example, Kuwait has enough reserves and sovereign wealth fund assets to finance 13.4 years of imports, while Bahrain could only finance over a year.

The evolution of oil prices and the capability of institutions to diversify income sources will be the main factors that ratings agencies will take into account in their grading decisions.

“For the time being, we expect the two factors to keep adding pressure on the downside. The EIA forecasted prices to remain close to $40 per barrel throughout 2017. Likewise, the momentum for reforms seems to be low, and we foresee only cosmetic measures such as a progressive reduction of fuel subsidies to be implemented,” Rof aid.

Major reforms like higher taxation (VAT, or income tax) and a large-scale restructuring of the public sector seem unlikely to materialise in the medium run, the Asiya report said.

Credit scores have a strong influence in the interest countries have to pay when they borrow. A cross-sectional comparison across 37 countries shows that credit ratings explain about 37.5% of 10-year sovereign bonds yield.

On average, the sovereign bond yield of any country is 0.4 percentage points higher than the one of a country with an immediately superior credit score. The intuition behind it is that a downgrade will increase the yield in the bond.

This causality has been proven in a number of academic papers which show how, over time, yields tend to react strongly to downgrades and upgrades. The reaction is particularly strong and predictable when the score falls into the speculative (also known as junk) grade.

Also, there is evidence that sovereign ratings have a significant influence on corporate yields, signalling an additional channel of impact to the real economy.

With rising spending, fiscal deficits will become the norm. They will have to be funded mostly by issuing debt, and a lower credit rating will accelerate the deterioration of the public finances.

The International Monetary Fund forecasted that, if countries do not adjust expenditure, the debt to GDP (gross domestic product) ratio would double by the end of 2016, reaching 30% of GDP, and increase to more than 70% of GDP by 2020.

“Reforms are the only way to go,” Rof added.

..