India’s turbocharged growth figures have been criticised by many analysts for giving too flattering a view of Asia’s third-largest economy. Closer scrutiny reveals another reason to worry: It’s the wrong kind of growth.

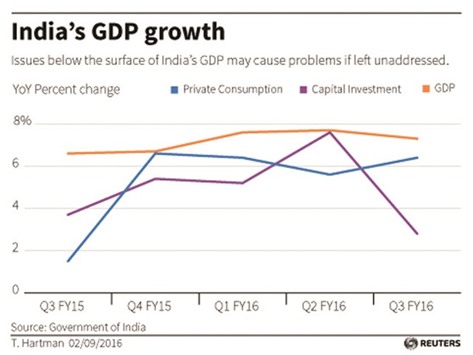

Consumer spending was the main driver behind India’s 7.3% growth in the October-December quarter, as a pick-up in urban spending more than compensated for subdued spending in rural areas where the majority of India’s 1.3bn people live.

But there was little sign of an upturn in private capital investment, which has been dormant for the past four years, despite efforts by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 19-month-old government to stimulate it through debt-fuelled higher public spending.

The higher spending by families and the government not only risks fanning inflation but also worsening household and national debt levels. Already retail loans are growing at a double-digit rate even as overall bank lending is crawling at its slowest pace in over a decade.

Personal loans that include loans for durable goods, housing and education are growing 14% year-on-year compared with 5.4% growth in overall bank credit, while credit card loans are growing at about 23% on year.

It would be better all-round if Modi were to make faster progress on bank, land and tax reforms. But legislation for the latter two items is stuck in parliament despite the government’s large majority in the lower house.

“If India wants to be the next emerging market star, it has to reform,” said Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at Capital Economics. “There is no alternative.”

Even after the prime minister’s much trumpeted push to expedite clearances for major projects, most remain stalled.

In the December quarter, projects worth $155bn remained stuck due to issues related to land acquisition and funding constraints, according to think-tank CMIE. New private investments in the same period dived 60%.

Finding it hard to borrow from banks worried by stressed loans at their worst level in 13 years, cash-strapped private firms have kept a lid on fresh capital outlay, dashing Modi’s hopes that higher public spending would provide a stronger investment multiplier.

Overall investment growth hit a 15-month low of 2.8% in the December quarter despite a 34% annual increase in public capital spending.

Underscoring the downbeat investment activity, Larsen & Toubro (L&T) – a bellwether of India’s engineering & construction sector – recently slashed its orders outlook.

“Policies are being announced, good intentions are there,” SN Subrahmanyan, deputy managing director at L&T. “What needs to be done is to hold the hand of the entrepreneurs to see that the concrete is poured on the ground.”

Nineteen road projects worth nearly $6bn, involving firms like Gammon and Madhucon, are stuck as developers have run out of cash and banks are reluctant to offer a lifeline, said a senior road and transport ministry official.

Even big projects have struggled to find takers. The $1.5bn Zojila Pass tunnel in Kashmir, India’s most expensive road project, languished for 18 months before being awarded to contractor IRB Infrastructure in January.

Statistically, India’s economic growth has overtaken China’s. But economists are questioning the official data, which they say has been overestimating the pace of expansion following a change made a year ago to the method GDP is calculated.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, due to present his third budget on February 29, is under pressure to relax fiscal deficit targets to further ramp up public spending to give the economy more momentum.

But the move is likely to further worsen India’s debt dynamics. The federal debt-GDP ratio is set end the fiscal year in March at 50.8%, according to Reuters’ estimates, rising sharply from 46.8% in 2014/15 due to a sharp slowdown in nominal economic growth.

A higher fiscal deficit would also undermine the fight against inflation. GDP data shows private consumption is outpacing investment. With a robust 6.4% annual growth, consumption contributed roughly half of overall spending growth in the December quarter.

A hike in salaries and pensions of government employees later this year is further expected to boost consumption, raising the risk of putting upward pressure on prices.

Meantime, the government is struggling to make progress on other fronts.

Modi has spelt out a plan to nurse ailing state banks back to health. Its implementation, however, remains patchy.

Similarly, no progress has been made on simplifying rules on land sales or on a major indirect tax reform that would eliminate customs barriers between states and, for the first time, create a single market nationwide.

..