Now that most economic sanctions on Iran have been lifted, the international Islamic finance industry needs to brace itself for fundamental changes when the world’s largest Shariah-compliant banking system readies to enter the global financial stage.

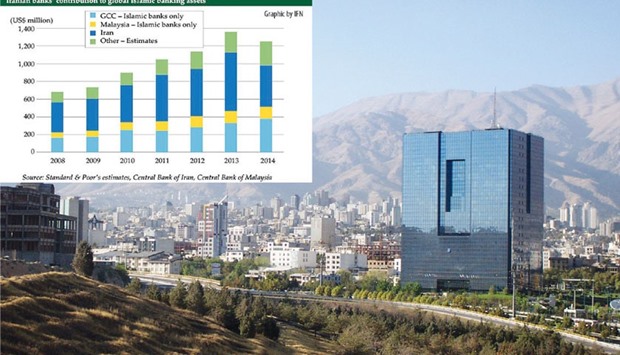

Iran, the only Muslim country besides Sudan where the entire financial industry is based on Shariah law, currently accounts for more than 40% of the world’s total Islamic banking assets, or around $482bn. That’s more than in Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and the UAE combined, which trail far behind with Saudi Arabia holding an 18.5%-share, Malaysia 9.5%, the UAE 7.3% and Kuwait 5.9%, according to data by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

Iran’s Islamic banking assets are also close to ten times the ones of Qatar.

Given the OIC’s forecast that Islamic finance assets will be growing steadily to around $3.5tn by 2018, Iran could easily cross the $1tn-asset mark by then which is not unrealistic given the urgency for cash-strapped Iranian public and private companies to raise liquidity after years of isolation from the international finance industry.

Analysts such as Ramin Rabii, CEO of Tehran-based investment firm Turquoise Partners, expect that a large number of sukuk and other Islamic financing vehicles will hit the world market soon and indeed reshape the industry whose leadership Iran had to leave to Saudi Arabia in the past. Estimations are that there are approximately 180 Iranian companies from many sectors, including manufacturing, hospitality, transport and other core industries, considering Islamic bond sales in 2016. Adding to that, the country requires funds for its infrastructure development programmes earmarked for the next decade worth an estimated $1tn.

Looking back, the banking system in Iran was nationalised after the revolution of 1979. Shortly thereafter, in 1983, the Law of Usury-Free Banking was passed, and on March 21, 1984, interest free banks started to implement Islamic banking, and Iran’s banks grew to large institutions, with a number of them, such as Bank Melli, Bank Saderat and Bank Mellat, today being listed among the largest Islamic banks in the world by assets. The three alone hold combined assets of around $140bn at official exchange rates, and this volume could grow considerably after another estimated $100bn of Iranian assets – mainly from oil sales – frozen on foreign accounts are now being released as sanctions got lifted.

However, analysts point out that the road back into the global finance system for Iran could be bumpy as the long isolation withheld Iranian banks from implementing globally accepted reporting and compliance standards, and restoring ties of its formerly stand-alone banking system to global financial institutions – even to other Islamic banks – could prove regulatory and technically difficult. Not only that many state and private Iranian banks are in dire need to repair their balance sheets and impose stricter standards, for example those on money laundering and minimum reserve requirements, they will also have to handle their problem with non-performing loans which peaked at 17% of total loans in 2013, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Another problem is that Iran’s version of Islamic finance is in some aspects markedly different from that practiced in other Muslim-majority states as it is based on Shia jurisprudence, which often diverges from mainstream Sunni jurisprudence in other Muslim states. Sunni scholars have repeatedly questioned the “rightfulness” of Iranian Islamic banks, and sukuk issued in Iran could probably have trouble to find investors in countries such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE or Malaysia, a recent study by the International Islamic University of Malaysia

pointed out.

The building of Iran’s central bank in Tehran. Iran, the only Muslim country besides Sudan where the entire financial industry is based on Shariah law, currently accounts for more than 40% of the world’s total Islamic banking assets, or around $482bn.