In his end-of-2015 missive, Holger Schmieding of the Hamburg investment bank Berenberg warned his firm’s clients that what they should be worrying about now is political risk.

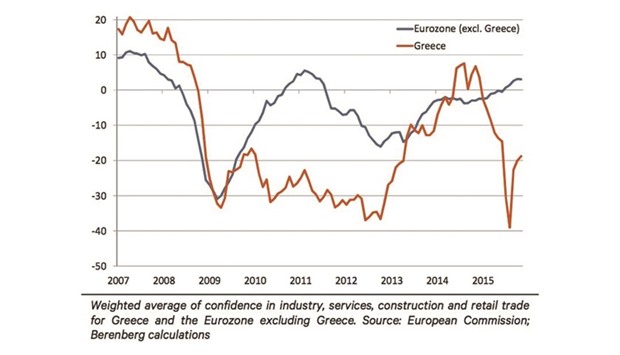

To illustrate, he posted the diagram (right), showing how business confidence collapsed in Greece during the late spring of 2015, and picked up again only after my resignation from the finance ministry. Schmieding chose to call this the “Varoufakis effect”.

There is no doubt that investors should be worried – very worried – about political risk nowadays, including the capacity of politicians and bureaucrats to do untold damage to an economy. But they must also be wary of analysts who are either incapable of, or uninterested in, distinguishing between causality and correlation, and between insolvency and illiquidity. In other words, they must be wary of analysts like Schmieding.

Business confidence in Greece did indeed plummet a few months after I became finance minister. And it did pick up a month after my resignation. The correlation is palpable. But is the causality?

Consider the following example. Business confidence fell in September 2001 (following the terror attacks on New York and Washington, DC), while Paul O’Neill was US treasury secretary. Would Schmieding label a chart showing that decline the “O’Neill Effect”? Of course not: the drop in business confidence had nothing to do with O’Neill and everything to do with fears about global security. The correlation with O’Neill’s tenure was irrelevant.

Similarly, in the case of Greece, the collapse in business confidence happened under my watch. But the cause was that our creditors, the so-called Troika (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund), made clear that they would close down our banking system to force our government to accept a fresh extend-and-pretend loan agreement.

Before these threats were issued, business confidence was actually picking up in Greece. Indeed, the day after I presented my reform and fiscal proposals to the City of London investor community, stocks rallied impressively. (Indeed, during my tenure in the finance ministry, real GDP grew more than it had done during the last two quarters of 2014, which Schmieding identifies as a period of increasing confidence.)

So, what caused the huge drop in business confidence during my tenure? Was it my policy proposals – jointly authored with Jeff Sachs (with input from Norman Lamont, a former Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer in the United Kingdom, Harvard’s Larry Summers, and James K Galbraith of the University of Texas) – that were responsible? Or was it the Troika’s explicit threat of bank closures (which were actually imposed when we dared to put our creditors’ ultimatum to the Greek people in a referendum last July)? In other words, was it the “Varoufakis effect” or the “Troika effect”?

To answer this question in ways that are helpful to investors, an analyst must at least make an effort to establish whether the observed correlation points to a causal link. Reading our policy proposals and comparing them to the Troika’s programme would have helped. Unfortunately, this would have required work that some analysts prefer not to do.

The relevant question is whether we were right to confront the Troika – a central plank in our January 2015 electoral platform – or whether we should have signed up to our creditors’ “Greek programme.” My view is that we had no alternative but to resist the Troika’s plan.

The reason is simple: the Greek state became insolvent in early 2010. From May 2010, this insolvency was addressed by means of sequential extend-and-pretend loans on conditions that were guaranteed to shrink national income, investment, and credit. A case of insolvency was made increasingly worse by continuing to pretend that it was a mere liquidity problem.

Was the Greek economy on the mend in late 2014? Of course not. Nominal GDP never stopped shrinking, public and private debt continued to become less and less sustainable, and all along investment and credit remained comatose. Without debt restructuring, a low target for the primary budget surplus (net of debt payments), a “bad bank” to deal with non-performing loans, and a comprehensive reform agenda that tackles the worst cases of rent seeking, Greece is condemned to permanent depression.

Alas, the Troika was in politically motivated denial and deeply uninterested in our policy proposals. Time and again, they simply demanded capitulation.

To be sure, we could have handled that confrontation better. But for an analyst to blame the victim of such financial violence is not only morally reprehensible, but also constitutes terrible service to his clients (who, for example, may be lulled into a false sense that Greece is on the mend now that Varoufakis has been forced out).

Thankfully, there are diligent analysts, like Mohamed El-Erian, to whom sensible investors can turn. And their verdict is clear: Greece’s downturn in 2015 was due to the “Troika effect”.

Yes, political risk in Europe is clear and present. But it emanates from the Troika’s unwillingness to reform itself and to rethink its failed policies. - Project Syndicate

- Yanis Varoufakis, a former finance minister of Greece, is professor of economics at the University of Athens.

graph