If a Bedouin in Jordan offers you a coffee, you must accept it. “You have to drink the first cup,” explains Ali Hasaseen — it’s basic manners.

“But you should consider more carefully whether you want to drink the next cup. If you drink the second cup, you’re promising to stand by your host’s side in battle,” Hasaseen continues with a laugh.

By Bedouin tradition, the second cup represents the sword that protects you, while the third is for relaxation. The fourth you always have to refuse — that is the local custom of politeness too.

The whole Bedouin family is gathering to greet visitors to the Dana Nature Reserve in Jordan. Father Muhammad Hasaseen roasts the coffee beans, then brews the coffee and rings the bell to call together any neighbours who might want a cup — another ancient ritual in this part of the world.

But today only the family is present.

The hand of every guest is shaken. There are around 400 Bedouin in the 300-square-kilometre reserve and they all live off tourism. Yet they make sure every visitor feels welcome.

The journey to meet the Bedouin clan begins at the top of a mountain, in the 15th-century village of Dana. It’s then a hike of five to eight hours through a canyon to the valley where Hasaseen’s family lives.

The path, which reaches heights of more than 1,000 metres, winds its way down through steep cliffs and along dried-up river beds and bare fields, the stillness only occasionally broken by the bells of herds of goats.

Today there’s only one group on the trek — and that doesn’t seem to be unusual, as the locals appear pleased to have a bit of company.

One shepherd stops on his donkey to ask for a cigarette and then stays to attempt a little conversation. Two villagers later approach the group, offering bread made from flour and salt that they’ve baked simply over the glow of a campfire.

There are still some tourists visiting Jordan these days, but far fewer than a just a couple of years ago.

That’s perhaps because Jordan borders not just on Israel, the occupied West Bank, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, but also on Syria with its rebel armies and above all the Islamic State.

“The tourists don’t see the difference. They lump the whole region in together,” says tour guide Aiman Tadros. “But Jordan is safe.”

The stagnation in tourist numbers can also be seen at the ad-Deir monastery in Petra, the city famous for its monumental architecture half cut into the rock.

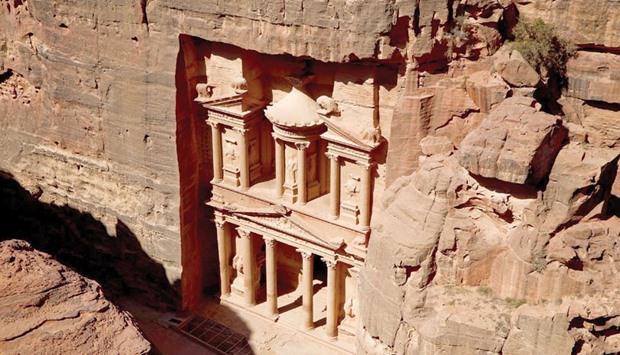

To reach the city you have to walk or go by donkey or camel for several hours. The dramatic Siq path, the main entry to the ancient city, climbs past burial sites, bizarrely eroded cliffs and temples before the visitor finally reaches a small, narrow gap in the rock which then opens out to reveal the impressive facade of the Treasury, one of Petra’s most well-known landmarks.

Despite being a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the new Seven Wonders of the World, there are no tourists in sight, just a donkey ambling by.

Jordan’s tourism industry is in crisis — tour guides say that visitor numbers are only around 30 per cent of what they were in 2010.

“Nobody used to be able to stand here for long or take a photo in peace,” says tour guide Tadros, pointing at the Treasury.

“The situation has become so bad that this summer the Bedouin held protests to get more help.”

The Bedouin make their living from maintaining the ancient city as well as other tourist highlights in Jordan.

The Jordanians are doing their best to adapt. There are security checks at hotel entrances and the tourism board has launched a marketing campaign which includes a visitor pass giving free entrance to 40 tourist attractions.

“We’re doing everything we can to win back tourists’ trust and get them to come back,” says Mahmoud Zawaida, leader of Captain’s Desert Camp.

The Bedouin live in one of the most unusual places in Jordan, perhaps the world: the Wadi Rum desert, also known as the Valley of the Moon, where the landscape is so unearthly that a Hollywood blockbuster, The Martian, about an astronaut stranded on Mars, was filmed here.

The Wadi Rum is a valley surrounded by weirdly shaped granite, basalt and sandstone mountains up to 1,750 metres high, with naturally formed bridges, canyons and ravines.

UNESCO declared the valley a mixed natural/cultural World Heritage site in 2011.

Here too, tourism has taken a hit. The area surrounding Wadi Rum was once prepared for regular busloads of tourists — the enormous parking lot is a testament to that. But today only four buses are parked there.

Most tourists no longer come on package holidays as groups, but rather alone, like young backpackers. In twos or threes they share a jeep across the magnificent red landscape.

“Vast, echoing and god-like” is how Lawrence of Arabia once described the Wadi Rum. It’s easy to see what he meant. —DPA

The Treasury, the most celebrated on the rock-cut buildings in Petra, Jordan. It is 43 metres high.