By Andy Home

London

Monday saw the release of China’s detailed metals trade figures for November.

This monthly event used to be hailed by the market as a confirmation that all was well with the manufacturing world.

Sure there were fluctuations in the import volumes with analysts poring over the figures in an attempt to draw out seasonal and stocking patterns in the world’s largest buyer.

But these were only variations on the underlying bullish theme, namely that China’s industrialisation and urbanisation programmes were fuelling a seemingly insatiable appetite for all things metallic.

Even a surge in exports of zinc and nickel in the second half of 2014 could be explained away as a one-off de-stocking event in the wake of the Qingdao port scandal and the resulting unwind of the metals collateral financing trade.

Such a one-dimensional view of China no longer works.

In truth, it stopped working some time ago. The so-called supercycle ended a couple of years ago but without anyone really noticing. It was only this year that the narrative itself collapsed.

There is no single unifying theory to replace it. Everyone’s struggling to work out to what extent China’s “slowdown” is cyclical, structural or, most likely, a confusing mish-mash of both.

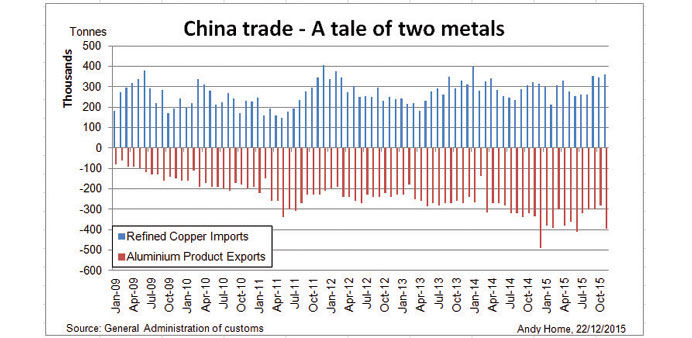

And that complexity is there to see in the country’s trade flows, where what comes out of China is now as important as what goes in.

Metals such as copper still conform to the old bullish narrative.

If you were to look just at China’s trade figures, you might be forgiven for wondering what all the doom and gloom is about.

Imports of refined copper totalled 3.25mn tonnes in the first 11 months of this year, representing only the most marginal of drops from last year, just 20,000 tonnes in volume terms.

Indeed, factoring in slower exports, China’s net imports actually rose by 1% over the period.

This is even more remarkable when you consider that the country has been importing ever greater volumes of copper concentrates to make its own refined metal. Imports of 1.44mn tonnes (bulk weight not metal contained) hit a fresh monthly record high in November and cumulative imports have already matched last year’s record tally.

Of course low prices in themselves might explain the resilience of refined imports, particularly if the government stockpile manager, the State Reserves Bureau, has been quietly buying up metal.

But the combination of strong metal and raw material imports suggest continued underlying growth in Chinese copper demand. The pace of growth may have slowed but it is working off a bigger base, translating into higher volumes.

Moreover, this year’s slower growth looks more cyclical than structural.

China is still investing heavily in its power grid, a positive for copper usage, but spending has been running below target this year with an inference that it may be due a sharp acceleration in the coming period, an inference supported by November’s 31% jump in grid investment.

Consumer goods sectors, meanwhile, have been working off downstream inventory, while automotive output is rebounding under targeted stimulus in the form of a cut in the sales tax on small-engine cars.

Viewed this way, the despondency in the copper market, particularly in China itself, may be a negative psychological feedback loop created by low prices rather than a collapse in demand.

Things look very different, however, if you look at the steel sector.

What goes into China is nothing compared to what is flooding out in the form of steel products.

Exports in the first 11 months of this year were almost 102mn tonnes, equivalent to the combined production of the whole of North America.

This is no cyclical phenomenon.

It is a function of two huge structural problems within China.

The first is a step-change in steel usage, largely reflecting the bursting of an unsustainable real estate and construction bubble.

China simply built too much too fast and it’s going to take a long while for that to work itself out. Beijing can tweak the process by targeted infrastructure spending but the type of breakneck construction growth seen in recent years is never going to return.

Only the big iron ore producers still think that China’s “peak steel” moment is yet to happen. The combination of falling production, down 2.2% in January-November, and accelerating exports suggests otherwise.

And that’s the second big problem for China’s steel sector. China also built too much production capacity too fast. Caught in a toxic landscape of falling demand, negative operating margins and high debt, many mills are literally exporting to survive.

China’s aluminium sector shows worrying signs of a similar malaise.

Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The opinions expressed are his own.