Bloomberg

New York

When banks began to scale back financing for energy companies earlier this year amid the slump in oil prices, some of Wall Street’s savviest asset managers sought to capitalise by lending at high rates.

That didn’t work out so well, as crude continued to plunge and lenders were stuck with losing positions. Now, banks are again contemplating credit cuts. But this time hedge funds and private-equity firms are showing more reluctance to step in.

“Those so-called lenders of last resort are not out there this time around,” said John Castellano, a managing director at the consulting firm AlixPartners who focuses on advising energy companies. “Many were burned and are staying away.”

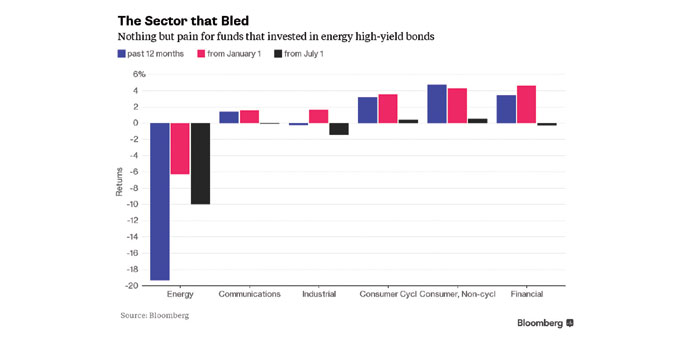

This wariness threatens to create a liquidity crunch for oil-and-gas drillers that have relied on relatively cheap funding for their operations. After investors snapped up more than $37.5bn of bonds issued by junk-rated energy companies in the first six months of 2015, just $5.9bn has been raised since then, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. And about $1bn of that came in the form of a distressed- debt exchange for Halcon Resources Corp in which the owners of some of the company’s beaten-down bonds agreed to swap their unsecured notes into higher-yielding and higher-ranking obligations that gave them a better claim on the company’s assets.

“Lenders are much more timid when considering new issuance as compared to earlier in the year,” said David J Karp, a partner at Schulte Roth & Zabel who specialises in distressed investing. “In the secondary market, there is appetite for distressed loan-to-own plays at the right levels but lenders still need to have the confidence in the driller’s ability to execute.”

Nonbank creditors have been fuelling the energy industry’s growth for some time. Investing behemoths including Oaktree Capital Group, Blackstone Group and KKR & Co raised more than $20bn for investing in the sector this year. Many have paid dearly. Blackstone’s credit unit GSO Capital Partners was among the lenders that saw almost all the value of their investments in the unsecured bonds of KKR-owned Samson Resources Corp wiped out after the unit filed for bankruptcy last week. It bought the company’s unsecured bonds early in the year, hoping to orchestrate a debt exchange that would give it better claims on the assets. But the negotiations failed because the value of the assets dropped further, leaving bondholders with residual claims that were immaterial. Christine Anderson, a spokeswoman at Blackstone, Carissa Felger, a spokeswoman for Oaktree at Sard Verbinnen & Co, and Kristi Huller of KKR declined to comment.

“Many fell on their faces and they no longer want to be part of the race,” said Marshall Huebner, co-head of the restructuring practice at law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell. “At the beginning of the year, everybody was raising money for distressed investments. You couldn’t show up at a cocktail party without hearing about all the people raising distressed-energy funds.”

In the second quarter, fundraising dried up. Hedge fund Sound Point Capital Management, which manages about $7bn, considered raising capital to target energy companies but put the plan on hold because “we didn’t think the timing was right,” said managing partner Stephen Ketchum.

While Sound Point has stayed away from the sector for the past four years, it’s continuing to listen to pitches from desperate borrowers.

“In June, we had no discussions about rescue financing, now we are talking to six or seven companies,” Ketchum said. “Liquidity is very important for the companies now. Borrowers that had easier access to conventional sources of financing when oil was at $65 per barrel have fewer options today.”

Meanwhile, the message from banks, which are under pressure to cut their oil-and-gas holdings, has been loud and clear: There will be less leniency come October.

On top of all that, firms such as Goldman Sachs Group and Jefferies Group have reported significant losses on their distressed-debt trading desks, much of it incurred from the energy sector.

“Investors are staying away,” said David Tawil, co-founder at distressed hedge fund Maglan Capital. “Even for funds that are interested, they are waiting until it’s very near to the credit-line resets in order to be as informed about current and near-term oil prices as possible.”