By Gautaman Bhaskaran

Once, Indian director Shekhar Kapur told me at the Cannes Film Festival that the next big wars would be fought over water. This was soon after he had launched his project, Paani, at the Festival.

Known for movies like Bandit Queen (about the notorious dacoit Phoolan Devi) and Mr India, Kapur said his work was based on a book by Maude Barlow, Blue Covenant: The Global Water Crisis and the Coming Battle for the Right to Water and scripted by David Farr.

Set sometime in the future, Paani would dramatize how water shortage would affect relationships between individuals, cities and nations. The beautiful young daughter of the chairman of the world’s largest water corporation arrives in the Upper City of Plentiful. On a chance encounter in the impoverished Lower City, she is kidnapped by the young, handsome water warrior. A love story that changes minds and methods, Paani will be set to music by AR Rahman.

Kapur added that water could well become a weapon in the future with corporates taking over its distribution. “This is what I hope my work will draw attention to, provoke a debate and hopefully help find a solution to this grave problem...Paani is the story of young love caught in the flurry of conflict and war between two cities, one that is rich and waterful, and the other that is poor and waterless, where water rats are forced to steal the precious liquid.”

Unfortunately, Kapur’s water war never took place, and his project has been reportedly shelved.

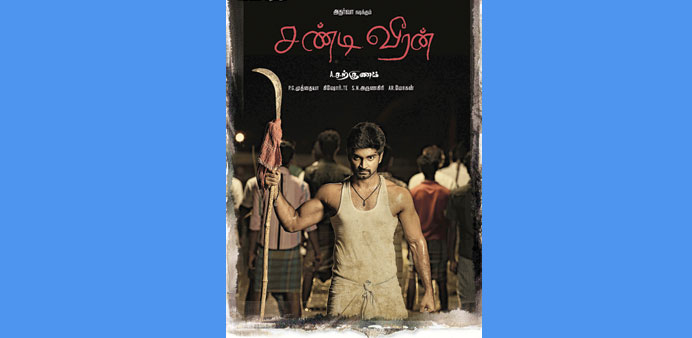

However, interestingly, Tamil cinema, renowned for its boldly novel themes, has just presented A. Sarkunum’s (Kalavani, Vaagai Sooda Vaa) Chandi Veeran — a gripping work on how two villages fight over water, killing and destroying in the process.

Paari (played by Atharvaa Murali) grows up with the memory of a nightmarish day when his father was speared to death during a fight between two adjoining villages over water.

Twenty years later, the feud continues — getting bloodier by the day. When a rich mill-owner (Lal) in one of the two villages refuses to let his pond be used by the other — its only source of drinking water — even contaminating it, the conflict merely worsens. Pari’s love for the mill-owner’s daughter, Thamarai (Anandhi), further complicates matters.

Chandi Veeran could not have been better timed. It comes at a period when Chennai and several other parts of Tamil Nadu are frighteningly close to a water famine.

Not just this, but Tamil Nadu has been at loggerheads with the neighbouring states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh over the sharing of Cauvery and Krishna waters respectively. Often, the political uncertainty over this issue and the concessions given at times by Karnataka to Tamil Nadu have led to agitations. Karnataka farmers feel that they are being deprived of adequate water for crop irrigation, while their counterparts across the border contend that their own supply is not enough for any meaningful cultivation.

It is no different with the Krishna water that partly feeds Chennai city.

Sarkunam tells me during a brief chat the other day that drinking water is indeed a pressing problem. There are 410 villages in Tamil Nadu alone where ground water has turned salty, because of various factors. One of them is marine erosion. And, thousands of villages will “turn salty” in the next decade if steps are not taken to check this.

In the context, Chandi Veeran appears aptly timed. But long, long ago in 1981, K Balachander, who gave us innumerable socially relevant works, made Thaneer Thaneer — a powerful political drama about how corrupt politicians were using water scarcity to their own selfish ends. In a way, Sarkunam’s film seems like an extension of Balachander’s yeomen effort to awaken the world to a looming crisis.

Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai

When Saeed Mirza created Albert Pinto in 1981 and asked him why was he getting angry, the celebrated director used a “maamooli” motor mechanic to convey and lambast the ills of India’s downtrodden. It turned out to be a cult film with Naseeruddin Shah brilliantly portraying the angst of Pinto’s ilk. As a Christian mechanic, he befriends some of Mumbai’s upper-class car owners following their advice that only lumpens go on strike and if one were to work hard and sincerely, one would get rich some day. But Albert realises the futility of his own dream and the sheer hollowness of the rich men’s advice when his mill-worker father gets beaten up by the anti-socials hired by the affluent owners. That day, Albert begins to direct his anger towards the rich and the powerful.

Now, Soumitra Ranade (who made the delightful children’s movie, Jajantaram Mamantaram) is all set to recreate his own angry young man in a new film, also titled like the original, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai. In a chat with this writer on Sunday morning over the telephone from Mumbai, Ranade says that his movie is not really a remake of the Mirza classic. “Rather it is a conceptual remake...where I have used anger as a central point of focus like in Mirza’s work. This time, it is the anger of the middle class, their anger against corruption, a non-functioning administration, exemplified by Albert Pinto.”

The film centres on Albert, who leaves home one fine morning without telling anyone where he is going. His girlfriend Stella, his mother and his brother, Dominic, are worried about him. The movie captures Pinto’s journey in a series of flashbacks and conversations with the worldly-wise driver, Nayar.

Ranade avers that “Albert’s anger stems from the experiences that life has presented him with – the personal injustice meted out to his father and the unfairness inflicted on humanity at large. It is this anger that takes him to Goa, to settle a score that he believes will help him lead a life of dignity.”

Ranade adds that Albert stands for change. “The dream of an equal India is long dead. Despite the tremendous progress made on the industrial and technological front, most people in the country are unhappy. There are stupendous price hikes, farmer suicides, the Naxalite movement, the growing regionalism and factionalism; the onslaught of terrorism, questionable women’s safety, the rural poverty and the urban stress, communalism, unrestrained corruption... the list is never ending.

“My film epitomises all the anger these maladies trigger in the common man in contemporary India. For me, Albert Pinto is the catalyst for transformation — from a despondent middle class, driven only by the ideology of the Rupee — to an angry class, which begins to ask questions and demand answers. Personally, the movie is a culmination of a prolonged, despairing struggle. As Pinto says in the movie, ‘it was as if a bulb had broken inside my stomach’. The making of the film meant removing each and every little piece of glass carefully.”

Kaul, who plays Albert Pinto, was noticed in movies like Kai Po Che and City Lights, and one waits to see him in upcoming works like Bijoy Nambiar’s Wazir, Prakash Jha’s Gangajal 2 — and of course Ranade’s Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai.

And Kaul’s screen lover will be Nandita Das, who will essay a part (Stella) made unforgettable by Shabana Azmi in the original version. Das, often referred to as a thinking actress, has done some remarkable work in films like Fire, Earth (both by Toronto-based Deepa Mehta), Jag Mundhra’s Bawandar and Mani Ratnam’s Kannathil Muthamittal. Her directorial debut, the 2008 Firaaq, was a political thriller with a celebrity cast (Naseeruddin Shah, Deepti Naval, Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Paresh Rawal).

Ranade has incidentally created a rank new character in his work. Saurab Shukla (what excellent performances in Jolly LLB as the belching judge and as the godman in PK) will be Nayar, a friend of Albert.

Ranade’s work is nearly finished, but the last leg of his journey still needs Rs30 lakhs, which the director hopes to collect through crowd funding. One knows that last year’s Mumbai Film Festival took place only because crowds funded it after Reliance withdrew. One also knows that Bikas Mishra’s Chauranga was able to can the last of the shots through crowd funding.

One hopes the crowds will help cool Albert Pinto’s “gussa”.

* Gautaman Bhaskaran has been

writing on Indian and world cinema for over three decades, and may be e-mailed at [email protected]

PROMOTIONAL IMAGE: The poster for Chandi Veeran.