By Dave Birkett/Detroit Free Press

For a decade, Charlie Sanders was one of the best tight ends in the NFL, a sure-handed pass catcher who helped revolutionize the position.

When Sanders’ playing career ended in 1977, a year after he suffered a serious knee injury, he remained a staple of the organization, first as a broadcaster, then an assistant coach, and most recently _ since 1998 _ as a member of the personnel department.

“The ultimate Lion,” said Sanders’ good friend, former Pistons star and ex-Detroit mayor Dave Bing.

The ultimate Lion died Thursday after a seven-month battle with cancer. He was 68.

Sanders will be most remembered for his Hall-of-Fame playing career. He played 10 seasons for the Lions (1968-77), finished his career with 336 catches for 4,817 yards, and retired as the team’s all-team leader in receptions.

But to many, both inside the organization and beyond, he was much more.

“Today we lost one of the greatest Detroit Lions of all time,” Lions president Tom Lewand said in a statement. “Charlie was a special person to the entire Lions family for nearly a half century. While never forgetting his North Carolina roots, ‘Satch’ became the consummate Detroit Lion on and off the field. He was a perfect ambassador for our organization and, more important, was a true friend, colleague and mentor to so many of us.”

Sanders served the Lions for 43 years over parts of the last five decades, the longest of anyone outside the Ford family that owns the team.

As a player, he was a dynamic pass catcher in an era of blocking tight ends. He never had more than 42 receptions in a season or 656 yards, but made seven Pro Bowls and wowed teammates with his hands and athleticism.

“Just a tremendously great athlete,” said Hall-of-Fame cornerback Lem Barney, a teammate of Sanders’ for 10 years. “He was always a believer that we could win. He always thought if he could get the quarterback to throw it to him he was going to catch it. He made some acrobatic catches. I’m telling you, one-legged, one arm in the air, floating through the air almost like a Superman. If you threw it to him he was going to find a way to catch it.”

A third-round pick out of Minnesota in 1968, Sanders was selected to the all-decade team of the 1970s and the Lions’ 75th anniversary team.

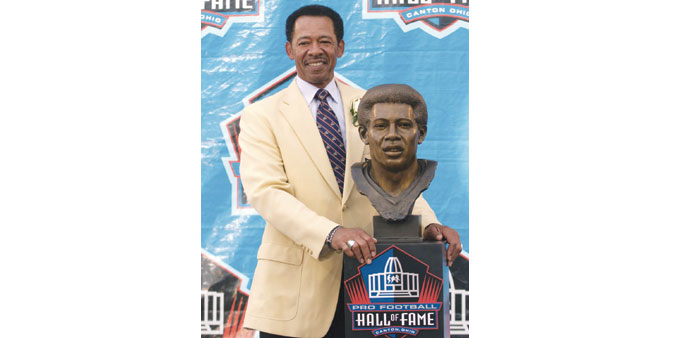

He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2007, and chose Lions owner William Clay Ford to give his induction speech.

“I think Charlie was pretty unique in his relationship with Mr. Ford,” Bing said. “There are a lot of players that played for the Lions that maybe even never met him, and Charlie had, for whatever reason they clicked, and Charlie had this personal relationship with him. It’s unheard of that a player being inducted into the Hall of Fame would be inducted by the owner of the franchise. So that’s unbelievable and that’s one of the things that I think Charlie cherished, that relationship with Mr. Ford.”

Sanders suffered a knee injury in a preseason game against the Atlanta Falcons in 1976 that ended his career and ultimately led to the discovery of the cancer that claimed his life.

In November, doctors found a malignant tumor behind Sanders’ right knee while he was being prepped for knee replacement surgery.

Sanders underwent multiple rounds of chemotherapy after surgery and was confined to Beaumont Hospital in recent months, where visitors were limited as a way to conserve his energy.

After Sanders’ playing career, he joined the Lions’ radio broadcast for seven seasons as color commentator (1983-88, 1997) and spent eight years as an assistant coach (1989-96), where he coached receivers and tight ends.

In 1995, he coached a receivers group that included Herman Moore and Brett Perriman, the first two teammates in NFL history to each catch 100 or more passes in the same season.

Sanders joined the Lions’ front office as a player personnel scout in 1998 and was moved to assistant director of pro personnel in 2000, a role he held until he was hospitalized.

Off the field, Sanders’ foundation, the Charlie Sanders Foundation, provided scholarships to high school students in Michigan and North Carolina and most recently raised funds for student heart-check programs, a cause he took up after hearing the stories of Wes Leonard and Chris Keenist, the son of Lions senior vice president of communications Bill Keenist who was forced to give up football because of an undiagnosed heart condition.

Last week, as Sanders was fighting cancer, his foundation presented a $3,000 check to the Wes Leonard Heart Foundation to provide automated external defibrillators to high schools.

“I loved the guy,” Keenist said. “I used to tease Charlie, but growing up in my small town south of Pittsburgh we had one NFL player come from our town and he was a tight end that played for the Detroit Lions and his name was Craig Cotton. So every year at Thanksgiving, we’d be so excited and he’d never get on the field because of Charlie. And I didn’t like Charlie because I’m thinking, ‘If it wasn’t for this guy, our hometown hero would be playing football.’ So I didn’t like Charlie, and then you get here and I loved him like a brother. He was the best.

“There was no one that was more selfless and more giving, that truly walked the walk and talked the talk when it came to giving back and being thankful for what he had. You know the bible verse to whom much is given, much is required, and he lived that every day because he felt he was truly blessed and all he did was give and give and give.”

Hall of Famer Charlie Sanders