By Jerry Brewer/The Seattle Times

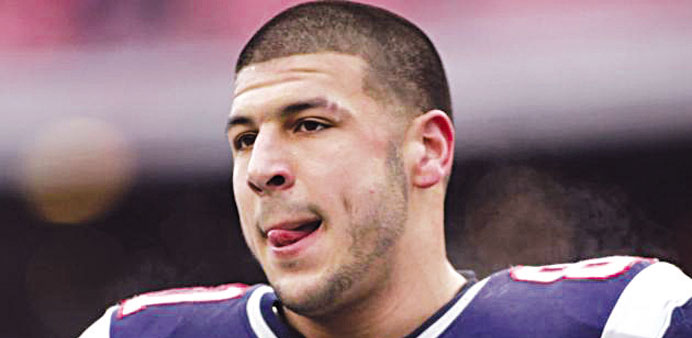

After he was found guilty of first-degree murder last week, Aaron Hernandez creased his forehead, pursed his lips and resorted to a tactic too common in his menacing life: intimidation.

The 25-year-old former NFL star shook his head at the jury and mouthed, “You’re wrong.” He licked his lips and shot a defiant stare. It was a harrowing moment. It was exactly how you’d expect Hernandez to react to a conviction.

Three years ago, Hernandez was one of the best tight ends in football. He was so good that the New England Patriots gave him a $40 million contract extension in August 2012. Soon after, he and his fiancee, Shayanna Jenkins, welcomed a daughter into the world. Hernandez bought a 7,100-square-foot home for his growing family.

His story seemed like a familiar NFL tale: Roughneck uses football as an outlet, evolves and makes an amazing life for himself. But Hernandez didn’t change. He left his hometown of Bristol, Conn., but he never ditched the violence that began in his youth.

In Hernandez’s case, sports didn’t reform him. Sports provided a convenient excuse to dismiss his problems. When Hernandez was getting into fights, failing drug tests and suppressing suspicion of more deadly acts, there were always coaches, administrators or executives at Bristol Central High School, the University of Florida and the New England Patriots who enabled him by not taking football away. He was too talented to dismiss. They couldn’t have possibly known the monster they were allowing to develop.

Now, a jury whose members admitted to crying during deliberations has taken down Hernandez. Last Wednesday, he was sentenced to life in prison without parole after being found guilty in the murder of Odin Lloyd. And Hernandez still has to stand trial for the 2012 killings of Daniel de Abreu and Safiro Furtado, murders for which he was indicted last May.

A horrifying truth has become clear after a two-year process: The NFL once employed a $40 million murderer. And he may have been a disturbingly prolific killer.

No American sports league has knowingly dealt with a possible psychopath. Even though Hernandez last played in the NFL two seasons ago, he is still the league’s burden. The NFL will always be mentioned with his name. He is the shame of a great game. Whenever a player is accused of a violent act, Hernandez will be referenced, and questions of how the league can curb violence will remain a significant issue. As much as Hernandez should be considered a thug who merely happened to play in the NFL, he’ll forever be used as evidence when people want to put football on trial.

Though the Patriots were fooled into believing Hernandez was on the right path, they will stand as a cautionary tale for teams that make character concessions because of talent. It could’ve happened to just about any team in the league, but it didn’t. It happened to a team that has won four Super Bowls the past 14 years. The Patriots knew Hernandez’s history, and even in giving him that $40 million extension, they made sure to protect themselves in case he got in trouble.

The lesson of the Hernandez story is complicated. It shouldn’t be flatly a message for teams to ignore players who had a rough upbringing, because many of those athletes turn into good citizens who play the game with admirable grit. But it’s a reminder to be diligent in researching players, and when it’s obvious that a talented young star has a disturbing history, you have to protect the franchise, no matter how difficult it is to win and find talent.

Ultimately, though, Hernandez is a random, dangerous criminal. He’s not a symptom of uncorrectable problem with the NFL or the game of football. But he did exploit a culture that gives second, third and fourth chances to extraordinary talents.

If only the enablers had known they were making a deadly exception.

Today, Hernandez sits in a maximum-security prison in Walpole, Mass., less than two miles from Gillette Stadium, where he was once a star with the No. 81 stitched on the front and back of his jersey. His uniform will be gray scrubs and tight shoes with no laces. The former $40 million man will have the option to work in jail, with wages starting at 50 cents per hour, according to The Boston Globe.

Hernandez once had the good life. Instead, he chose the thug life.