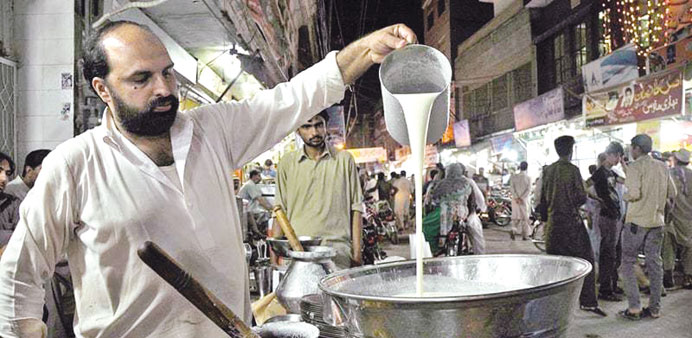

Lassi has been enjoyed across the country for generations to beat the summer heat.

DPA/Islamabad

It is still early on a summer day, but Munnawar Chaudhry is sweating profusely as he gulps down a glass of lassi.

White or plain lassi is a mix of yogurt, milk, water and ice, with sugar or salt added for taste.

The drink has been enjoyed across the country for generations to beat the summer heat.

“I cannot live without lassi in the summer,” Chaudhry says. “I drink it whenever I feel thirsty as it keeps me cool.”

Summer temperatures in Pakistan can soar above 45 degrees Celsius, and dehydration is a serious problem. Hundreds of people died in June in a heatwave that hit the south of the country.

The heat is compounded by electricity shortages which render air conditioning units useless and make refrigeration difficult.

For many, freshly made, locally produced drinks are the answer.

Motor-rickshaw driver Saeed Ahmad has just stopped by a roadside stand for a glass of shakanjbeen, a drink of water, lemon, salt and ice.

“It is cheap compared to Coke or Pepsi and also good for summer,” Ahmad says.

The restorative drink is one of the more affordable, with a typical glass costing less than Rs10.

Other traditional drinks include the plum-based alo-bokharay ka sharbat, or sattu, made from roast barley seeds, water, brown sugar and sometimes fruit.

The high-end sardai, known as the royal drink, is made from almonds and pistachios ground with milk, sugar and ice, and fetches up to Rs100 a glass.

At the simpler end of the spectrum, sugarcane juice and flavoured milkshakes are also popular, says Raja Sohail, a juice seller.

“People use these drinks to quench thirst and cool down body temperature in hot and humid conditions,” he says.

Less common but equally traditional is the cannabis-laced bhang, seen by some as an alternative to beer in a country where alcohol is unavailable except in a few Western-oriented hotels.

The leaves and flowers of the widely available female cannabis plant are dried and crushed, and mixed with dry fruits to make a paste.

It is then added to lassi, spices and ice to make drinks of different flavours.

Bhang is not openly sold as it is illegal, and some disapprove of its intoxicating properties. But the drink is still in demand, especially in the hot southern province of Sindh and its capital Karachi.

Hafeez, a journalist and former heavy bhang drinker, says that no drink matches it if consumed in the right quantity. It has a soothing effect, quenching the thirst and producing positive feelings.

But some experts say the locally-made drinks are sometimes an unhealthy option, and mostly used by people who cannot afford bottled beverages.

Drinks at roadside stands often include high levels of added sugar, salt, spices and colouring that “are sometimes not good for health,” doctor Arif Azad says.

The sellers try to allay such concerns. “I have been selling alo-Bokharay ka sharbat for more than a decade,” says Mohamed Aslam, who inherited the business from his father. “Nobody has ever complained about its quality.”