DPA/Karachi

Private investigator Masood Haider is a man in a hurry.

On one of his previous visits to the southern Pakistani city of Karachi, his car was shot seven times, probably by an irate relative of a client, Haider said.

He established his private detective agency five years ago after he was unable to find anyone to spy for him in a defamation case he was fighting in court.

It gave him the idea to help other people in similarly personal matters. He did not expect the kind of cases he would primarily be dealing with.

About half of his clients now hire him to get evidence on cheating spouses, or “sour marriages,” as he calls them.

“It happens all over the world, and it happens in Pakistan as well.

It’s normal. We cannot be in denial,” Haider said.

In Pakistan, adultery can be punishable by death, sometimes by village mobs for “honour crimes.” While divorces are increasing, the number of such legal separations remains negligible.

“When the husband or the wife cheats, it’s a very painful situation for the other individual in the relationship,” Haider said.

“The prerogative is on the person cheated upon: he or she could decide whether to give the relationship a chance.”

Haider laughs, and says he has found that both men and women cheat. He also said he does not provide the information of a cheating spouse “to any third person, but just to those in a legitimate relationship, who are entitled to the information.”

In one of his favourite cases, he discovered that a lover of one Karachi man’s wife was in fact a wealthy businessman, who was hired by the husband himself to be a driver and helper around the house.

The lover-in-disguise was revealed by a female detective, whom Haider had sent undercover as a maid in the woman’s house.

“Can you believe the amount of trouble people go through to have an affair?” he said.

He was also hired by a woman to investigate her husband, who it turned out was sleeping with his wife’s own sister. “That is not allowed in Islam, against the morality and all norms.

But he is doing it,” Haider said.

Some of his other services include tenant and pre-marital screenings, recovery of money, locating a missing child and intellectual property and copyright infringement.

The agency is registered with the government as a consultancy firm, but some controversies surround the detective work, which is usually done by police and intelligence agencies.

In 2012, then-interior minister Rehman Malik said he would order an investigation into the agency, but no action was taken.

“If someone is conducting surveillance and monitoring a person’s activities for financial gain, it is a breach of privacy,” police officer Ashraf Naveed said.

Haider said the biggest challenge is “to draw the line that should not be crossed.”

“We cannot deal with cases that are being dealt with by government authorities, like the police or federal investigators, or any of the intelligence agencies,” he said.

Many Pakistani women would use the services of a private detective if they could afford it, said political commentator Sadia Hyatt.

“Many women do not have any option but to tolerate their husband’s behaviour. This is one avenue that gives them a way out,” she said.

One British-Pakistani man said he asked for the agency’s help with land acquisition, since no regulatory authority in Pakistan would hand out correct information on land before the purchase.

“Overseas Pakistanis buy land here, and later find out that they were cheated by a fake owner. I investigate if the seller is really the owner of the land,” Haider said.

Pre-marital screenings are currently in demand, he said. In Pakistan, most marriages are arranged, with older female relatives playing matchmakers.

“I have seen the worst and the best here. I usually move among the elite because of the kind of services I provide, and I have seen them holding a peg (of whisky) in one hand and prayer beads in the other,” he said.

Haider currently has 35 investigators on his staff, including retired military and police, as well as psychologists. He takes up to 60 cases a year, all of which he monitors personally.

The former military aviation officer likens himself to a mix between Sherlock Holmes and Columbo, a homicide detective from a 1990s US television drama.

His military background helps, he said, but would not elaborate.

“The army has taught me everything. Pakistan’s army is one of the best institutions in the world,” he said.

His fees range from $5,000 upwards.

“The service is not easily accessible to everyone,” he said.

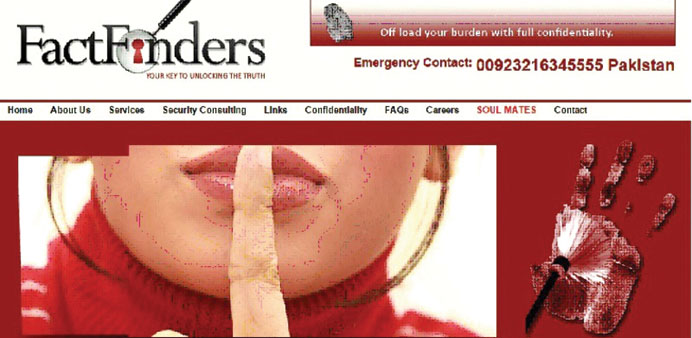

A screengrab from the website of FactFinders.com.pk, a private detective agency specialised in catching cheating spouses and performing background che