By Rachel Finn and David Wright/London

Drones, it seems, are suddenly everywhere. They have buzzed through the plot lines of American television thrillers like 24 and Homeland, been floated as a possible delivery option by the online retail giant Amazon.com, seen action in disaster zones in Haiti and the Philippines, and hovered menacingly over French nuclear power plants. This once secretive technology has become nearly ubiquitous.

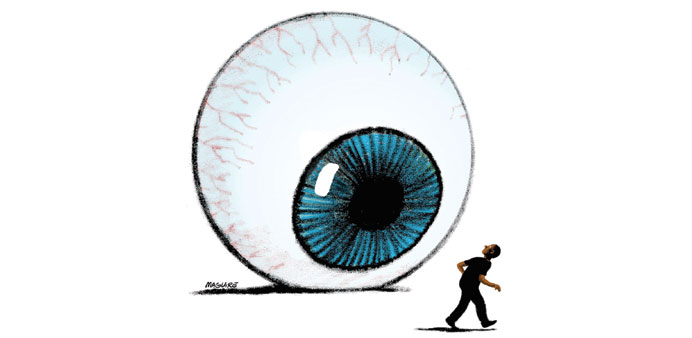

With policymakers in the US and Europe committed to opening civilian airspace to non-military drones, the pilotless aircraft will only become more common. So it is crucial that the unique challenges they present to civil liberties and privacy are quickly identified and addressed.

For starters, drones are significantly changing the way data are collected. Until now, most civilian drones have been equipped only with high-resolution cameras, offering police officers, search-and-rescue teams, journalists, filmmakers, and inspectors of crops and infrastructure a bird’s-eye view of their surroundings. But that is about to change. Manufacturers are experimenting with drones that can collect thermal images, provide telecommunications services, take environmental measurements, and even read and analyse biometric data. In addition, some operators have become interested in collecting “big data,” using a range of different sensors at the same time.

Meanwhile, drones are becoming smaller, allowing them to infiltrate spaces that normally would be inaccessible. They can peek through windows, fly into buildings, and sit, undetected, in corners or other small spaces. Their size and silence mean that they can be used for covert surveillance, raising concerns about industrial espionage, sabotage, and terrorism. The next drone that flies over a French nuclear power plant might be too small to be noticed.

The price of drones is plummeting, too. Already, a basic model can be deployed for no more than a few hundred dollars. Commercial operators, who want to maintain good customer relations, have an interest in using drones responsibly. But private individuals are likely to have fewer scruples about using them to spy on neighbours, family members, or the general public.

Action is necessary. But, though the privacy implications of small, ubiquitous, low-cost drones, equipped to collect a broad range of data, are obvious, the proper response is not. Simply banning them would deprive society of the many benefits drones have to offer, from their deployment in dangerous, dirty, or dull duties to their lower operating and maintenance costs compared to manned aircraft.

Using drones for crop dusting, pollution monitoring, or most search-and-rescue operations is unlikely to raise serious concerns. But other applications, especially by police, journalists, and private citizens, clearly could. The sheer variety of the technology’s potential applications makes it almost impossible to regulate with legislation alone. Instead, interested parties at all levels need to assess the potential impact on privacy, data protection, and ethics on a case-by-case basis.

Well-meaning drone operators need to consider carefully how their activities might violate privacy and breach civil liberties, and they should take steps to minimise these effects, using – to the best of their abilities – existing tools, such as privacy-impact assessments. Data protection authorities, civil-society organisations, and privacy officers in businesses and public organisations should publish guidance on drone use, as they have done for other existing and emerging technologies. The guidelines governing the use of closed-circuit television could serve as a good starting point – but must be supplemented to account for the different types of data a drone can collect.

Drone manufacturers need to play their part as well, including by providing guidance to assist users – especially private citizens – in operating their products within the bounds of the law. Serial numbers should be included, so that drones are traceable. Civil authorities should complement these efforts by considering how existing legislation on privacy, data protection, trespassing, and harassment could be used to prosecute operators who infringe on human rights. Finally, insurance companies can provide the right incentives by exploring the market potential arising from liability in the event of misuse or accidents.

The challenge is both urgent and complex. The rights of citizens need to be protected before the market, and the drones themselves, really take off. - Project Syndicate

- Rachel Finn is a senior research analyst at Trilateral Research & Consulting, where she conducts research on privacy, data protection, and ethical issues relevant to new technologies. David Wright is Managing Partner at Trilateral Research & Consulting and the author of Surveillance in Europe.