By Henry I Miller/Los Angeles Times/MCT

The World Health Organisation (WHO) is nothing if not opportunistic, impulsively jumping on every public health issue that makes the front page. And, of course, it always calls for lots more money to throw at the disease-of-the-month.

The latest on the WHO’s radar is the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, which has tallied about 1,500 cases. To address it, WHO wants more than $430mn - from governments, development banks, the private sector and in-kind contributions.

The plan, outlined in a document to be published soon, purportedly seeks to reverse the trend in new cases within two months and to stop all transmission in six to nine months. Interestingly, the amount of money the WHO now says it needs is a sixfold increase over the $71mn it called for less than a month ago.

This grandiose proposal sounds like something a precocious but naive undergraduate might come up with for a project in Public Health 101. Ebola is highly lethal, killing more than half of those it infects, but it is not highly contagious. Transmission requires intimate contact with bodily fluids from someone who is infected and symptomatic, so it is highly unlikely to cause a widespread epidemic.

Infectious diseases, many of them preventable and treatable, remain the scourge of poorer populations, including those that inhabit much of Africa, but the Ebola virus is not high on the list. Malaria is. Consider the WHO’s own assessment of its importance:

“About 3.4bn people - half of the world’s population - are at risk of malaria. In 2012, there were about 207mn malaria cases ... and an estimated 627,000 malaria deaths. Increased prevention and control measures have led to a reduction in malaria mortality rates by 42% globally since 2000 and by 49% in the WHO African Region.”

But in virtually all poor, malaria-endemic countries, there is inadequate access to antimalarial medicines (especially artemisinin-based combination therapy). That $430mn now sought for Ebola would buy and distribute a lot of those drugs (and vaccines to prevent diseases including hepatitis A and B and human papilloma virus) and benefit far more people.

Aside from malaria, hundreds of millions of people suffer from neglected tropical diseases, including lymphatic filariasis and cholera. And the number of new cases of tuberculosis worldwide is increasing, with the growing emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of the bacteria especially worrisome.

Consider HIV/Aids. The Joint UN Programme on HIV/Aids (UNAids) reported last year that “new HIV infections have been on the rise in Eastern Europe and Central Asia by 13% since 2006”, and “the Middle East and North Africa has seen a doubling of new HIV infections since 2001”. According to the UN, funds are tight: “Investments focused on reaching key populations have not kept pace. ... In priority countries, only three in 10 children receive HIV treatment under 2010 WHO treatment guidelines. Children living with HIV continue to experience persistent treatment gaps.”

According to UN statistics, about 15% of the world’s population lacks access to safe drinking water. More than 2.5bn don’t have access to adequate sanitation, while “1.1bn were defecating in the open”. Primitive approaches to managing sewage continue to spread infections such as schistosomiasis, trachoma, viral hepatitis and cholera.

The bottom line is that in a world of limited healthcare resources, we need to make hard decisions that will deliver high-impact outcomes for the most people at the least cost. Spending nearly half a billion dollars on curbing Ebola virus infections would be a poor choice.

- Henry I Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. He was the founding director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Biotechnology.

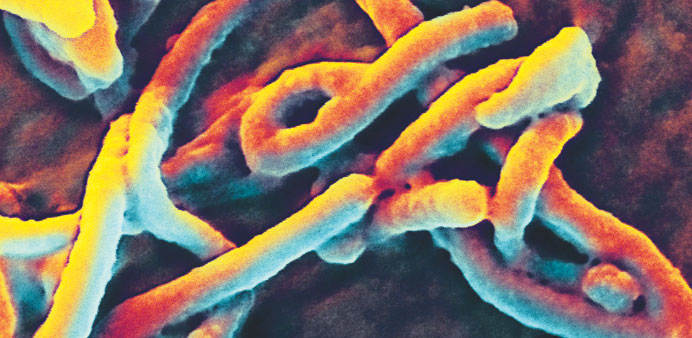

A scanning electron micrograph of the Ebola virus budding from the surface of a Vero cell of an African green monkey kidney epithelial cell line.