IANS

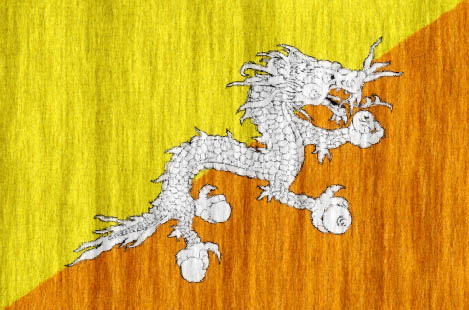

Thimphu

Boasting of more than 300 local rice varieties that have withstood varying weather conditions over the ages, Bhutan is relying on its seed bank - a conserve of seeds and other genetic resources of indigenous plants - to tackle food security issues arising out of climate change.

Nestled in the southern slopes of eastern Himalayas, Bhutan is the one of the world’s smallest countries, with 69% of its population of just 760,000 people dependent on agriculture. Around 56% are farmers, the community most aware of local symptoms of climate change that is perceived as a threat to the loss of on-farm agro-biodiversity, said Ugyen Tshewang, secretary of Bhutan’s National Environment Commission (NEC).

“Our National Gene Bank will definitely play an important role for us in tackling climate change because it has all the indigenous seeds. For example, there are more than 300 varieties of rice and many varieties of corn and others staples,” Tshewang said.

“The local varieties are more resilient because they have passed the test of time and are adapted to the local conditions they have passed through the cold weather, hot weather, frost and snow,” he added.

Tshewang was speaking on the sidelines of the just-concluded APN Second Science-Policy Dialogue, South Asia on ‘Global Climate Change: Reducing Risk and Increasing Resilience’ here organised by Asia-Pacific Network (APN) for Global Change Research in collaboration with the Bhutanese government.

The essence of a gene bank is to preserve a diversity of seeds for posterity and for research, Tshewang explained.

Established in 2005, it holds 1,268 accessions of cereals, legumes, oilseeds and vegetables.

Rice, maize, wheat, barley, buckwheat and millets are the major staple cereals that are cultivated in Bhutan, which is opposed to the introduction of genetically modified crops/food, Tshewang informed.

Officials estimate the presence of 350 landraces (locally adapted varieties) of rice, more than 40 of maize, 24 of wheat and 30 of barley in the country.

“We have also developed eight climate resilient rice varieties in the wake of climate change,” Tenzin Drugyel, deputy chief of the ministry of agriculture and forests (MoAF), said.

Some of the local symptoms of climate change that Bhutan has seen recently include floods from a glacial lake outburst (GLOF) and erratic monsoons. A GLOF in 1994 affected 94 households and washed away 16 tonnes of foodgrain.

Then two years later, a fungus-induced rice blast cost farmers 80% of their harvest.

“In addition, there was heavy rainfall, flashfloods and landslides in 2004. Other indications are advent of new pests and diseases such as the northern corn blight in 2007,”

Drugyel said.

In the wake of these emerging challenges, among other interventions, Drugyel said, evaluation and adaption of genetic resources (plants and animals) resistant to biotic and abiotic stresses including drought, pests and diseases, is crucial.

In fact, the Sector Adaptation Plan of Action (SAPA) of the agriculture and forest ministry says Bhutan is projected to experience a peak warming of about 3.5 degrees C by

the 2050s.

This is with the overall significant increase in precipitation but with an “appreciable change” in the spatial pattern of winter and summer monsoon precipitation.

As per the Community Perspectives on the On-Farm Diversity of Six Major Cereals and Climate Change in Bhutan report, research should focus more on these traditional varieties.

The paper, published January 27, was authored by various departments of the MoAF and UNDP-Thimphu’s Global Environment Facility-Small Grants Programme.

“Attention should be paid to the dissemination of locally adapted traditional varieties or using the local genes in the future crop breeding programmes,” Tirtha Bahadur Katwal, chief

author of the study, said.