The surgeons will thread the tube through a hole

beneath Haile’s chin so they may work the jaws without

obstruction. They will sew closed the hole, maybe pause

to stretch. Then comes four weeks of turning the screws

to construct Haile’s new face. By Tim Prudente

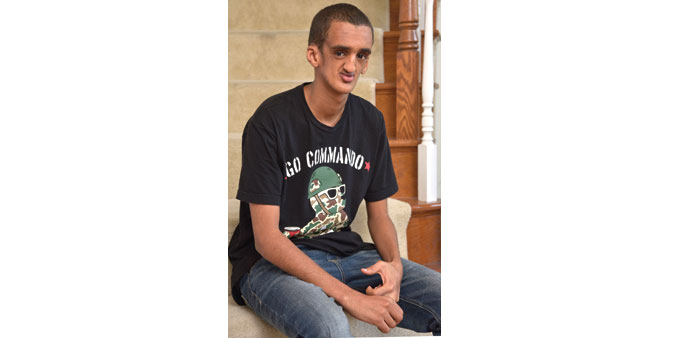

From one angle, it’s almost unnoticed: the droop of his nose, the concave cheeks, the pinched mouth with 13 teeth — three top, 10 bottom, too few to chew steak.

The face of a child.

But Filmon Haile is 19.

“Look how small it is,” said Dr Edward Zebovitz, lifting a plaster cast of Haile’s jaws. The bottom one is about an inch long.

It’s a Friday morning at Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, Maryland, the day Zebovitz, the former chief of oral and maxillofacial (face) surgery at the hospital, will embark on the most demanding operation of his 20-year career.

Down the hall, Haile waits with his mother. They travelled nearly 7,000 miles from the Horn of Africa, the city of Asmara, capital of Eritrea — where Haile would hide his face beneath a black scarf.

“When I met him, I was like, what did he have?” Zebovitz said. “There was no syndrome that he fell into.”

Haile arrived with medical records, though. He was two years old when a tumour grew on his cheek.

American doctors, Zebovitz said, wouldn’t try radiation on a so young a child.

Radiation, on Haile’s face, stunted growth. His body developed, but his face lagged.

“I have a problem meeting people,” Haile said. “They laugh at me and ask many questions.”

Surgery “is going to change my life completely,” he said.

Zebovitz spent weeks planning the cuts along cheekbones, eye sockets and jaws. Titanium devices will be screwed on cut bone beneath the skin. These devices, called distractors, will extend screws behind Haile’s ears.

The screws will be turned and, millimetre by millimetre, bone will separate; the process is similar to the way dental braces work. The titanium plates open like elevator doors, and bone regrows in the gap.

“It’s all engineering,” Zebovitz said.

Haile himself will turn the screws each day.

A third screw will extend from Haile’s gum line and, when turned, shift forward his jaw, a third of a millimetre per turn — about half an inch when finished — but still a journey considering the fine contours of the face.

“If it’s off just a matter of 10 degrees, it could start the bone growth in the wrong direction,” said Dr Douglas Fain of Kansas City, Mo, vice president of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, who is not participating in the surgery.

The technique was developed in the 1950s by Russian professor Gavriil Abramovich Ilizarov, mostly to lengthen the bones of patients with uneven legs. In the 1990s, Fain said, it was applied to bones of the face.

Still, Haile’s surgery is ambitious.

“Because of radiation therapy at such a young age and just how big the magnitude of the movements are,” Zebovitz said.

Haile’s lower jaw will shift forward 12 millimetres in four weeks.

At 7:30am, the operating room is prepared for 10 hours of surgery.

Haile’s mother, Zemzem Abedalla, kisses her son on the face. His cheekbones are paper-thin.

Zebovitz met Haile in May 2014.

Zebovitz flew to Eritrea to perform free surgery on patients with cleft palates for his charity, Surgeons for Smiles.

During training, Zebovitz saw four clefts, and then encountered 25 during his first charity trip to the Philippines in the 1990s. Next came Bangladesh, Nigeria, Nepal, Caribbean Islands. His record: 71 clefts, five days.

In Eritrea, Dr Laynesh Gebrehiwet introduced Haile.

“I was never quite sure why she felt so strongly that I needed to treat him,” Zebovitz said. “She was very adamant. She cares about her patients so much. She just has some type of bond with Filmon. I respect her so much, I was like, OK.”

Zebovitz was given permission from the US State Department to bring Haile and his mother here. They arrived in March to stay with Mike Naizghi and his family. He’s a refugee from Eritrea who lives in Bowie, Maryland.

Zebovitz is performing the surgery free. Anne Arundel Medical Center is absorbing its expenses.

Dr Bryan Ambro, an assisting plastic surgeon, sews closed Haile’s eyelids. He cuts a crescent along the teenager’s scalp. Ambro wore his black sneakers today — scalps bleed.

The cut is widened, and resident surgeon Anish Chavda pushes a metal scrape against the skull. Four surgeons work the skin from the bone. An hour passes before they expose the cheeks.

They fold Haile’s face down on his chin.

Zebovitz drills through the cheekbones, thin as popsicle sticks. The titanium distractor is anchored with twists of a modified Phillips-head screwdriver.

More than four hours have passed; the jaws remain. But Zebovitz asks a nurse to call Haile’s mother.

The nurse dials as he’s preparing the breathing tube. The surgeons will thread the tube through a hole beneath Haile’s chin so they may work the jaws without obstruction. They will sew closed the hole, maybe pause to stretch. Then comes four weeks of turning the screws, those gears to construct Haile’s new face.

The nurse speaks gently into the phone.

“Everything is fine. Everything is OK. We still have a long way to go.” —The Baltimore Sun/TNS