He was eating peanuts in the hope they would control his allergy to peanuts. Counterintuitive? Yes. Medically risky? You bet. Brave? Definitely. Cynthia H Craft has the story

Nine-year-old Michael Lee, a bright boy who’s bound for fifth grade in the fall, lives with a serious, life-threatening medical condition. He suffers from a peanut allergy, a growing menace that can make breathing a matter of wishful thinking and anaphylactic shock a horrifying possibility.

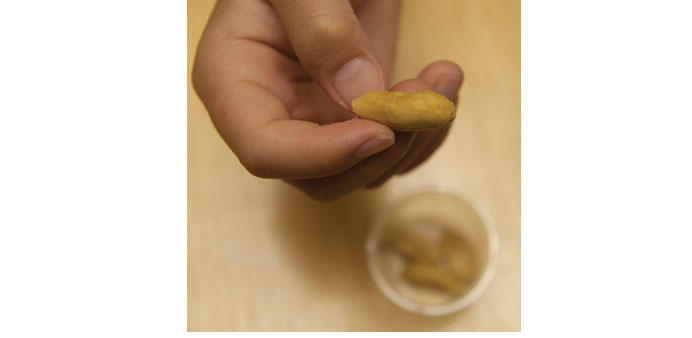

So why was Michael sitting at his family’s kitchen table on a sunny and breezy morning last week, calmly and compliantly munching peanuts, one by one, with his mother standing by?

He was eating peanuts in hopes they would control his allergy to peanuts.

Counterintuitive? Yes. Medically risky? You bet. Brave? Definitely.

Michael is the first child in Sacramento selected for enrolment in a novel, new treatment for nut-allergic kids. Developed by allergists at Mercy Medical Group, it’s the first such programme to be rolled out in the region. It’s called food oral immunotherapy or, more to the point, peanut desensitization.

Peanut allergies are exploding in number in babies and children. In response, Mercy developed the programme to introduce nuts to young patients in very small doses, gradually increasing the child’s exposure to try to lessen the body’s immune system reaction to peanuts.

Since Michael was 4, he has been rushed to the emergency room a number of times, said his mother, Geena Lee. First, for throat discomfort; then, head-to-toe hives; and finally, anaphylactic shock.

Lee said the family had two choices: One, to wait and hope Michael never has a lethal exposure to peanuts, a hold-your-breath option that breeds paranoia. Or they could weigh the risks and benefits of the new treatment and make an informed leap of faith.

“I don’t see this as exposing him to something dangerous,” Lee said. “I chose this treatment because the alternative is, what? To do nothing and be paranoid all the time?”

The science behind the treatment is like inoculation. For instance, flu shots contain minute amounts of viruses to protect people from influenza, and allergy shots of pollen-based solutions ease the symptoms of seasonal outdoor allergy sufferers.

Here’s the caveat: According to Mercy’s allergists, the peanut desensitization programme comes with “significant risk of a serious allergic reaction, including hives, swelling, bronchospasm, difficulty breathing, loss of consciousness and shock, which may necessitate emergency treatment and hospitalisation.” And, the unmentionable: risk of death.

Still, the pair of allergists running the programme, Drs Rubina Inamdar and Binita Mandal, believe they’ve developed an air-tight protocol to prevent harm from coming to the dozen or so children they treat. Over 18 months, the two painstakingly reviewed research and protocols of a handful of similar programmes across the country.

More allergies

No-one knows why food allergies — especially peanut allergies, considered the most dangerous — are growing at such a rapid pace. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, from 1997 to 2011, food allergies grew in number by 50 percent from 3.4 percent to 5.1 percent of American children.

Scientists are vexed, and continue to study the problem. A predominant theory is that our lives have become so clean, our homes and hands so sanitized, that our immune systems are confused. They have trouble locating germs and bad actors to battle, and end up targeting substances like the signature ingredient in an American staple, the iconic peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Other food allergies are triggered by milk, tree nuts, soy, wheat, shellfish and eggs, with eggs being the most common. Recently, buckwheat joined the list.

Inamdar said other countries are not seeing food allergies at rates even approaching the US rate. A study by the CDC in May 2013 found that children of families who are relatively well off financially had the highest rates of food allergies.

Interestingly enough, food allergies also appear to plague mainly urbanites and suburbanites. Even when country people move to the city, the protective effect that may come from living in a rural environment seems to vanish, Inamdar said.

“In terms of overall global allergy data, people living in extreme rural conditions seem to be getting exposure to all kinds of microbes, and so their immune systems have targets to focus on,” Inamdar said. Researchers have found that food allergies are rare in remote parts of the European countryside where hundreds of years of tradition dictates that people sleep with the cows they are tending, she said.

It follows, then, that research suggests that having a dog in the household may reduce the likelihood that kids will develop food allergies. Presumably, whatever the dog tracks into the house from the outdoors is enough to keep the body’s immune system busy. That’s a theory, at least, Inamdar said.

“There are lots of unanswered questions,” said Mandal. “We don’t have a smoking gun. We have an array of things to examine.”

Geena Lee noted that in the decades that food allergy rates have mushroomed, parenting has changed substantially.

“We don’t let our children play outdoors unsupervised anymore,” said Lee, as she observed her son carefully munching peanuts. “We don’t let them make mud pies.”

It was Lee who first ran across information about the unusual treatment method. She brought it to the attention of Inamdar, and a year later, the allergist got back to Lee with word that Mercy Medical Group was willing and ready to give it a go.

A tragic death

Then, the unthinkable happened. Last August, cheerful, red-headed Natalie Giorgi, 13, was enjoying one final night at Camp Sacramento with her family when she took a bite of a Rice Krispies treat at the campground in the Eldorado National Forest.

Right away, she knew something was wrong. She spit it out. Natalie had been taught to be extremely cautious and to avoid foods with peanuts, especially sweets, but had not expected to find the dreaded ingredient in treats passed out after a campfire.

Her parents observed her for adverse reactions; Natalie was given Benadryl and her father, Dr. Louis Giorgi, was standing by, ready to administer an EpiPen, a needle device that delivers epinephrine to counteract severe allergic reactions. Natalie seemed fine. Twenty minutes later, she suddenly vomited and had trouble breathing.

Natalie died before the three EpiPens her father administered had time to take effect. The El Dorado County Sheriff’s Office said the cause of death was severe laryngeal edema, a swelling of the throat resulting from a severe allergic reaction.

After that, “I lost a week of my life,” said Inamdar, who counts Giorgi among her colleagues. Natalie’s death so affected Inamdar that the allergist, who was then prepared to launch the programme, put it on hold for six months out of respect for the Giorgis and their loss.

Mandal said Natalie’s case, which increased awareness of the perils of peanut allergies, “just makes my heart sink.”

Months passed and then, in December, the allergists picked Michael as their first patient. The pair said they are very selective about whom they treat because the regimen of peanut desensitization must be followed precisely. They won’t take on a family whose caregiver may be unreliable, forgetful or unable to arrange transportation for required biweekly check-ins at Mercy’s allergy facilities, they said.

Michael was selected because he’s a responsible kid in a reliable family. “He’s practically more mature than I am,” Inamdar said. And although he’s in the vanguard, Michael is joined by 12 other kids who have since been added to the programme. Mercy’s allergists said they try to enrol one new patient a day, taking it slowly so they can continue to closely monitor the programme.

Establishing a safety net

Back in the Lees’ immaculate home, Michael was finishing up his morning dose of 6 grams of peanuts carefully measured by his mother on a digital scale. It was 7:30 in the morning, and the next dose would be precisely 12 hours later. The daily routine has Lee closely monitoring her son for signs of an immune-system reaction for one hour, keeping him from vigorous exercise for two hours and making sure he does not get overheated.

Michael’s treatment started with just a smidgen of peanut powder mixed into liquids or soft foods. Every two weeks, he would visit the Mercy allergists and every two weeks his peanut dose would increase a little bit more.

Currently, he’s reached his “maintenance” dose, one he’ll stay with for 18 months to maintain the benefits of the programme. If he quits the maintenance dose, his allergic reactions may return in full force. Lee believes there is a possibility her son may someday be free from his peanut allergy, but this is a promise the Mercy allergists avoid making to families.

“The purpose of this programme is not to cure a food allergy,” said Inamdar. “It’s to desensitize, and in doing so, establish a safety net in case of accidental exposure to the food,” Mandal said. — The Sacramento Bee/MCT

DIFFICULT CHOICES: The desensitization regimen is intended to keep the patient’s immune system from overreacting in the event of an accidental exposur