By Andy Home /London

Aluminium producers’ pain is becoming acute again. US producer Century Aluminum warned last week it would begin shuttering its Hawesville smelter in Kentucky in October “unless the current pricing environment substantially improves”.

Barring some sort of miraculous divine intervention, the number of operating smelters in the US looks set to fall to just seven from 13 prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009.

And more cuts will have to come, given a consensus view, even among producers, that the aluminium market is both in current over-supply and burdened by the dead weight of legacy stocks from past over-supply.

But will Century’s actions make any difference?

After all, we’ve been here before.

Overshadowed by its announcement on Hawesville was Century’s decision in July to dismantle permanently its Ravenswood smelter in West Virginia. Ravenswood has lain idle since 2009, a reminder that producer pain is nothing new in this sector and a warning that successive waves of cutbacks have failed to correct aluminium’s structural problem of excess capacity.

The uncomfortable truth for Century and its peers is that until something changes in China, there won’t be much change to the “current pricing environment”.

Hawesville, which started production in 1969, has a capacity of around 255,000 tonnes per year, although it has been operating at around 80% of that rate since a labour dispute in May, subsequently resolved. Four of its five potlines produce “high purity” metal grading 99.9% rather than the industry-standard 99.7%, according to Century’s website, although any corresponding “competitive advantage” has evidently been eroded by the collapse in aluminium prices.

Hawesville’s closure is likely to have a ripple effect on US supply-demand dynamics. It will increase further the country’s already significant reliance on imports and more of these will have to come from further afield since traditional US suppliers, such as Brazil and Venezuela, are also much diminished producing nations.

In theory, that should be supportive for local physical premiums. As the distorting effect of long load-out queues from London Metal Exchange warehouses in Detroit fades, the premium boom has turned to bust.

On the CME the September premium contract, indexed to Platts’ assessment of the US Midwest market, is currently trading at 7.1 cents per lb, or around $157 per tonne.

The loss of yet another US smelter should, at the very least, put something of a firmer floor under that premium. What Hawesville’s closure won’t do, however, is change the global supply-demand dynamics. It is simply too small a plant to do so.

More will be needed.

Maybe from fellow US producer Alcoa, which still has around 400,000 tonnes of annual capacity under active review.

Maybe from Russian giant Rusal, which has guided, albeit vaguely, to around 200,000 tonnes of higher-cost capacity cutbacks.

But even if these two aluminium giants delivered on 600,000 tonnes of extra capacity cuts, would it make any difference? Once, it would have done.

That was when the aluminium world was a different place, neatly divided into two “parallel universes”, in the words of Klaus Kleinfeld, chairman and chief executive at Alcoa.

There was China. And there was the rest of the world. The two were separated by China’s prohibitive 15% export tax on primary aluminium.

Back then what giants like Alcoa and Rusal did really counted in the world outside of China.

Now, however, those parallel universes have collided in the form of fabricated aluminium products flowing out of China in ever greater quantities. There were 340,000 tonnes of such exports in July alone, more than Hawesville’s annual capacity.

Adding perceived insult to injury for producers such as Century is the persistent speculation that some of those products are not really products at all, just metal that has been sufficiently transformed to duck the export duty and qualify for a VAT rebate.

Or, to quote Michael Bless, chief executive and president of Century: “The simple fact is that the recent significant decline in the aluminum price is being driven by unfair trade behavior over which our industry has no control.”

“Chinese overcapacity and the improper export of heavily-subsidized Chinese aluminum products have undercut an otherwise viable plant.”

The problem is that no-one is claiming that anything other than a small part of those Chinese exports are “fake semis”, as they have been nicknamed in the market.

The rest are “real semis”. And they have reduced to rubble China’s previous great aluminium wall.

The new aluminium market is a genuinely global one and one that is now dominated by China.

That’s why the world is still awash with aluminium.

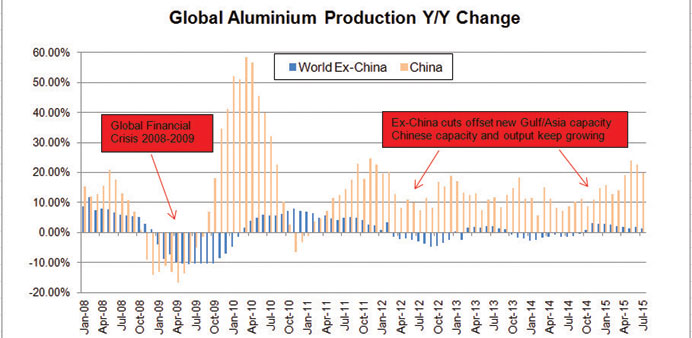

Non-Chinese producers have taken some 2.5mn tonnes of capacity out of operation since the GFC.

China, with a brief interruption at the height of the crisis, has simply carried on adding capacity and kept on producing more aluminium.

Andy Home is a Reuters columnist. The opinions expressed are his own.