Reuters/Madrid

Spain’s economy is growing at its fastest pace since 2007, though for many ordinary citizens times are harder than ever.

While tourists and higher earners are driving a consumer boom that propelled economic growth to 1% between April and June, the 5mn-plus unemployed and millions more in insecure and poorly-paid jobs are by and large spending less.

“I consider myself lucky to have found work, but our finances are still in crisis,” said father-of-two Pedro H, a property administrator.

Like many of the 430,000 Spaniards who got a job last year, he earns less than he did — 1,000 euros a month net for eight hours a day compared with €1,300 for six in a similar position in 2012, before the economic recovery began to take hold.

Reluctant to have his full name published, Pedro H also worries how long his job will last, given new laws that have made it easier for employers to lay off staff.

Spain exited an economic downturn in late 2013 following a six-year slump after a housing bubble burst, saddling the country with a mountain of debt.

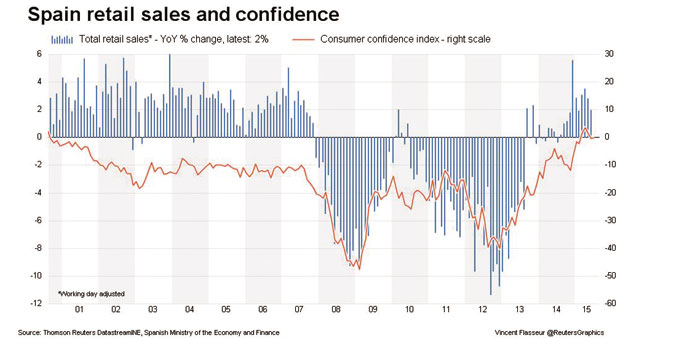

Underpinning growth now is a recovery in consumer spending, rising 1.0% in the second quarter as unemployment edges lower. That matched the quarterly rate of economic growth, which improved from a 0.9% reading in the first quarter, final data from statistics institute INE showed yesterday.

For the conservative government, seeking re-election before year-end and held up by euro zone policymakers as an austerity success story, the pick-up is good news. Spain forecasts the economy will grow 3.3% this year, among the highest rates in Europe.

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, trying to reverse a slump in popularity, still faces an arduous task to win over the many voters who doubt the extent of the turnaround.

His People’s Party (PP) is ahead in polls, but well short of a majority as newcomer parties led by anti-austerity Podemos and market-friendly Ciudadanos attract a steady groundswell of support.

Many voters perceive that, because of corruption, the powerful have remained immune to the crisis while the ordinary suffer.

A quarter of Spaniards in work are in temporary and often low-paid contracts and, according to a July poll, 75% of the population believe the economic situation is the same or worse than a year ago.

Retail sales increased for 11 months running to June, but the numbers mask deepening social divisions.

The INE institute’s spending survey for 2014 — well after the retail recovery took hold — showed households in which the main provider was unemployed spent on average 5.3% less than in 2013. OECD data also shows the wealth gap has widened during the period.

Tourism, which accounts for a tenth of Spain’s economy, has taken up some of the slack.

Many Spaniards in work are spending more too, though others remain reluctant to splash out, sensing that the good times before 2008 may never return.

“We go out a lot less than we did,” said Pedro H, who was unemployed for two years before finding work in December in Madrid.

Measured since 2008 when the downturn began, Spanish households are on average 15% poorer, with 4,673 euros less income per year, according to 2014 data from INE.

Spending on hotels, cafes and restaurants was down 24% over 2008-2014, INE said, although household budgets overall picked up 0.5% in 2014 versus 2013.

Rajoy projects unemployment will fall to just below 20% by the end of 2016, from 22.4% now.

But the rate, the second-highest in Europe, consistently tops polls of Spaniards’ biggest worries. In terms of strategy, Rajoy has focused on the purported danger to the economy posed by a left-leaning government.

Philippe Waechter, chief economist at Natixis Asset Management, says a weak euro, low oil price and expansive monetary policy all underpin the economy. The risk is perhaps that recovery in the rest of Europe is not as strong.

“I’m not sure that the general election will change the picture ...I think Spain is very different from Greece... (in) that people can now find jobs and the trend has now changed,” he said.

Others focus on the light at the end of the tunnel after tough-to-swallow reforms.

“It’s a well-balanced recovery, and a steady one, backed also by a steadily improving European recovery, and that is a very positive thing,” said Janwillem Acket, chief economist at Julius Baer.

But the feelgood factor has yet to filter through to the central Madrid bakery where 47-year-old Jose Gomez works.

“Some years back we employed three people. Now there are two, and my colleague works four hours more a day for practically the same wage,” he said.

“Since the start of the crisis our prices haven’t changed... but our costs are much higher. Things are harder than they were.”