By Arno Maierbrugger/Gulf Times Correspondent/Bangkok

Asia is on the way to become the “oldest” continent in just a few decades, with the number of people aged over 65 expected to rise from currently 300mn to close to 900mn by 2050, the Asian Development Bank warned.

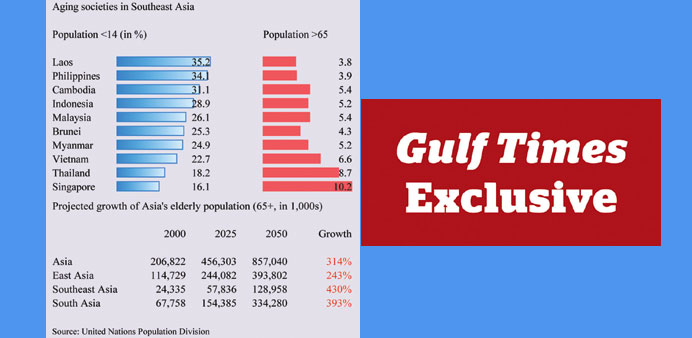

Based on numbers and calculations by the UN, the Asian population in this age group is in the process of increasing by 314% from 2000 to 857mn in 2050. Facing an unprecedented pace of their population ageing, Asian governments are now under alert to tackle this important challenge.

Moreover, the process of population ageing is occurring much more rapidly in Asia than it did in Western countries some time ago, and it occurs in some Asian countries at a much earlier stage of economic development.

In 2000, the average age in Asia was 29 years. An estimated 6% of the region’s total population were age 65 and older then, 30% were under age 15, and 64% were in the working-age group of 15 to 64 years.

While projections estimate that the proportion of the working-age group will be the same in 2050, there will be a dramatic shift in the proportion of children and the elderly. The proportion of under age 15 will drop to 19%, and the proportion of 65 and older will rise to 18%. The average age in Asia will be 40 years by then.

Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian Economic Research at HSBC Holdings, who recently did a similar report on Asia’s demographic shift, says that “Asia is ageing at an unprecedented rate – arguably the fastest the world has ever witnessed.”

Neumann points out that especially East Asian fertility rates are chronically and unsustainably low. Of the 224 countries in the CIA World Factbook, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macau and Singapore are in the lowest 16 for fewest children born over a woman’s lifetime. China’s relatively low fertility is a function of its three-decades of the one-child policy, which means a single working child will likely have to support several elders. China’s working age population shrank by 3.45m last year.

“The demographic trend is clear. The Asian tigers — Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan — are most affected, followed by China, Vietnam and Thailand. The Philippines, Sri Lanka and Indonesia are less affected,” Neumann says.

The biggest problem emerging for East Asian countries will be to sustainably finance their pension systems. Generally speaking, with economic development, workers tend to retire at younger ages. Although older adults are much more likely to work in Asia than in Europe or the US, the proportion of all Asian elderly in the labour force has already declined and is projected to decline further — from 38% of the population 65 and above in 1950 to 25% in 2000 and 22% in 2010.

This also puts pressure on the traditional family support system in Asia as social and economic change is continuing. In countries where fertility has been low for decades, the elderly have few adult children to provide support, and many of these children have moved away from their family homes. Marriage rates have dropped sharply in some countries, and women are entering the work force in increasing numbers. Middle-aged women, the traditional caregivers, are likely to have less time than they did in the past to care for elderly family members.

“Asia’s wrinkles start to show,” as Neumann puts it.

According to Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who last week held a speech in Bangkok on Asia’s future economic challenges, the “demographic trap” is equally challenging as the “middle-income trap” and the “environmental trap” which occurs through depletion of resources, and policymakers need to respond with structural solutions to the problem.