By Andy Home

On the surface at least, much has changed in the London Metal Exchange (LME) warehousing business over the past year.

But take a deeper look, and it is clear that the underlying structural problems are still there. The exchange has much more work to do if it wants to rectify a delivery system that has ruptured relations with some of its users and generated a spate of lawsuits in the US.

What the LME has done is add three new delivery locations, extending its global warehousing network to Kaohsiung in Taiwan, Moerdijk in the Netherlands and, for copper only, Panama City in the US.

Several new operators such as Whelan Metals, BTG Pactual and Independent Commodities Logistics have joined the ranks of registered warehousers, while other smaller companies such as Erus Metals and Scale Distribution have expanded their foot-print.

The exchange will also take some satisfaction from the reduction in the number of delivery queues even though its proposed rule change linking load-in to load-out rates is itself log-jammed in the UK legal system.

Not yet revealed are the results of logistics and legal reviews of the LME’s warehousing system, commissioned by the exchange. Either of them could yet prove as significant as the LME’s current assault on the queue model, which had been exploited so efficiently by Metro at Detroit and Pacorini at the Dutch port of Vlissingen.

Even after this series of changes, however, the exchange’s physical delivery function is still dominated by a handful of players and, more problematically, by operators tied to some of the world’s most powerful trading houses.

The total number of LME-registered storage units, excluding those holding steel, contracted marginally over the last 12 months to 666 from 678, primarily due to cuts by those companies most associated with load-out queues.

In the case of Impala Terminals, previously known as NEMS before being rebranded by its owner Trafigura, the attempt to build a queue at Antwerp never really got off the ground.

A rapid build-out in capacity has gone into reverse, with the number of Impala sheds at Antwerp falling to 12 from 26 last July as it scales back its LME ambitions.

Metro, currently owned by Goldman Sachs but with a “for sale” sign on it, reduced its footprint by 12 units over the last year, extending a retreat that began two years ago.

It is trimming its presence just about everywhere apart from its core LME operations in Detroit, where it still runs 27 sheds with 1.41mn tonnes of metal in them as of the end of June.

Even Pacorini, owned by Glencore, has tempered its previous capacity surge, reducing the number of storage units in Vlissingen by 12 to 41. That’s still the largest concentration of warehouses held in any one location by one company, mirroring what is still the largest concentration of metal in the system, 2.16mn tonnes at the end of last month.

The pull-back from Vlissingen has been partly offset by its increased presence elsewhere, particularly in New Orleans where Pacorini has opened a couple of new units, bringing its total to 34.

Over a two-year timeframe, the largest reduction in capacity, a net 28 units, has come from Henry Bath. This, however, doesn’t appear to be anything to do with queues, which it didn’t have, but with restructuring prior to a sale. The LME warehousing unit is included in a package of commodity assets being sold by JPMorgan to trade house Mercuria.

Others have moved into or expanded LME warehouse storage, presumably taking a view that decaying load-out queues at Detroit and Vlissingen will translate into wider distribution of LME stocks.

This is particularly noticeable in Detroit, where three new operators have appeared, although Whelan Metals marks more of a return than a debut. Bill Whelan is credited with being the original mastermind behind Metro’s massive expansion before the sale to Goldman Sachs in 2010.

Scale Distribution, owned by Macquarie Bank and Orion Finance, has also opened up shop, extending its bespoke warehousing model from Liverpool to Motown as well as to Panama City, Florida.

Joining the fray is the new warehousing arm of Brazilian investment bank BTG Pactual, which has opened units in Detroit, Owensboro and, most recently, Singapore.

Worldwide Warehousing Solutions (WWS), owned by trade house Noble Group, is the second-largest operator in Detroit with five units and 18,100 tonnes of registered metal at the end of June.

WWS hasn’t added to that tally in Detroit, but it has expanded into Antwerp and Vlissingen, lifting its total number of units to 17 from 10 two years ago.

Erus Metals, jointly owned by Barclays and steel trader Metalloyd, has also increased its presence in Antwerp, adding another three units to bring its total in the Belgian port to six.

But such incremental advances by some of the smaller LME warehouse operators are overshadowed by those of Steinweg, the grand-daddy of the LME storage business.

It added a net eight units over the last year, bringing its total to 175 and reclaiming the top spot from Pacorini, at least in terms of number of registered sheds if not volume of metal stored.

It is symptomatic of the underlying reality of the LME’s warehousing network.

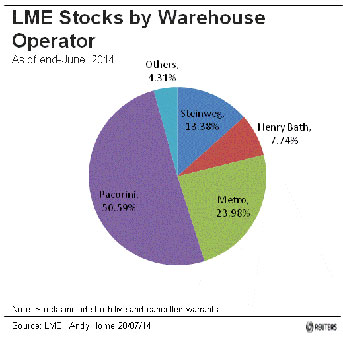

It remains dominated by the “big four”, namely Steinweg, Pacorini, Metro and Henry Bath (in that order).

Between them, they currently operate 505 registered LME warehouses, representing 76% of the total.

Moreover, there’s a gulf between their scale and that of the next largest operator. CWT operates 28 units, compared with the 70 run by Henry Bath, the smallest of the big four. This dominance becomes even starker when viewed in terms of the amount of metal stored, information that is now available to the market thanks to a new LME report.

As of the end of June, the big four accounted for almost 96% of all the metal in the LME system, with Pacorini taking the lion’s share with just over half of the 6.5mn tonnes either on LME warrant or awaiting load-out.

Andy Home is a columnist for Reuters. The views expressed are his own.