“I don’t take money

from rich people, or

government, or aid

agencies. This is my

philosophy. If the

common people

are the givers it

will last forever”

Each day the foundation gets 10,000 phone calls asking for help.

It covers the entire life cycle, from saving 40,000 unwanted babies

and taking care of them until they are adopted to collecting and

burying unclaimed bodies, writes Subel Bhandari

Inside a dingy, dim room in a busy Karachi neighbourhood, eight telephone operators are working in front of computer screens.

The doors are shut to keep out the traffic noise of this south-eastern port city, the business capital of Pakistan.

Every 8 to 10 seconds, a telephone rings in the operation room of the Edhi Foundation Hotline, a charitable emergency service that provides ambulances and other assistance to the needy and most desperate.

Calling the hotline number 115 is free. Each day the foundation gets 10,000 phone calls asking for help for everything from traffic accidents to terrorist attacks, says Mohammand Amin, in charge of the Karachi centre.

“Around two-thirds of them are fake or prank calls. But the rest, around 3,500, are literally calls for help,” he said, showing a computer screen with a Google Earth-like map of Karachi, with hundreds of small dots — each signifying an ambulance.

Edhi Foundation, a brainchild of Pakistani philanthropist Abdul Sattar Edhi, is the largest charity in the country.

The charity operates the emergency service across Pakistan with 1,800 ambulances, as well as three dozen rescue boats, two fixed-wing planes and one helicopter.

Alone in Karachi — the most-populated Pakistani metropolis and one of the most violent cities in the world — they have 350 ambulances on call day and night, spread like taxi stands over 150 different locations.

According to the Pakistan Human Rights Commission, there were around 3,000 deaths in the country last year attributable to criminal activities, sectarian, communal or gang-related violence, and police encounters.

“Bombs and guns are part of our daily life,” said Ghulam Farid, 28, one of the ambulance drivers from Lyari, Karachi’s most dangerous area.

But such is the respect that people have for the work of the foundation that there have been instances when an Edhi ambulance arrived at the scene of a gunbattle in full swing between police and gangsters, and the fighting stopped while the ambulance workers did their job.

“They would cease fire until bodies were carried to the ambulance, the engine would start and the shooting would resume,” the founder, Sattar Edhi, wrote in his 1996 memoir.

“I have nothing to fear because this ambulance is my defence. I have never faced any attack,” said Farid, who works 36-hour shifts, with a 12-hour break in between.

The hotline is just one of the Edhi Foundation’s activities.

Because of the calls to the centre, they also provide information to people looking for missing loved ones, Amin says, holding a big register with description of all the victims of accidents and attacks they have helped.

The foundation covers the entire life cycle, from saving some 40,000 unwanted babies and taking care of them until they are adopted to collecting and burying unclaimed dead bodies with Pakistan’s largest morgue that can hold up to 300 bodies at a time.

The foundation runs shelters for the homeless, the sick, the physically and mentally challenged, as well as 1,500 orphans — one of whom was once Amin, now in charge of the hotline.

There are also 17 shelters where women can seek refuge from domestic violence and other abuse as well as nursing homes, hospitals, and blood banks.

And every evening at 6pm, they provide food to the hungry in 18 places across Pakistan.

“Around 30,000 people eat from our free kitchen every evening,” says Anwar Kazmi, the head of Karachi office.

The foundation has also worked extensively in international relief, including the 1987 Lebanon War, the 2003 Asian tsunami, US Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and the 2007 Bangladesh cyclone.

Edhi started the charity in the early 1950s, arriving to Pakistan, then a new country, right after the 1947 partition of India.

The foundation’s yearly expenses today amount to millions of dollars, all of which is donated by the public.

“Our yearly donation is around Rs2 billion (US$20 million) in cash. And we also get tons and tons of donations in kind, like clothes, equipment, furniture, etc,” Kazmi said.

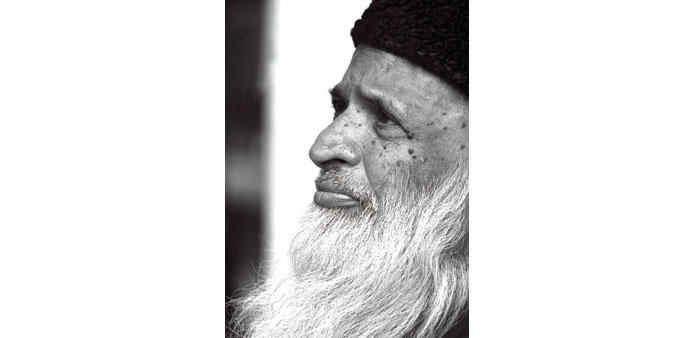

And at 86, Edhi still goes to the street to ask for alms.

“This is my habit, to go down the road, make a rally, and start asking for donations. This is what I do. This is what I am good at,” Edhi told DPA at one of his centres in Karachi.

“Common people, the poor, labourers, taxi drivers give me money. I don’t take money from rich people, or government, or aid agencies. This is my philosophy.”

“If the common people are the givers it’s sustainable. It will last forever if common people support a mission,” he said.

Considering such largesse from the poor, the philanthropist himself lives in a modest two-room apartment with his wife in one of their orphanages.

For most Pakistanis, Edhi is the greatest living philanthropist.

“Over the last 60 years, Edhi has singlehandedly changed the face of welfare in Pakistan,” notes a 2012 message nominating him for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Author Bina Shah in a recent article in the Pakistani monthly Herald called Edhi and his wife “our living saints.”

“In treating each and every Pakistani as a human being, regardless of religion, ethnicity or background, they have become role models for the nation.”

Edhi says that Pakistan is seeing more violence and instability due to increasing gap between the poor and the rich.

“Where there is hunger, where there is greed for material, there will be poverty and violence,” said Edhi.

Last year, half a dozen robbers stole more than Rs10 million (a million dollars) in cash, along with 5 kilograms of gold and some jewelry from a safe in his orphanage.

While the money was from donations, the gold and jewelry were given to him for safekeeping because he is considered safer and more trustworthy than a bank.

He is not vengeful.

“To feed their hungry bellies, to feed their children, the poor will rob and steal. They will do anything. It is their right.” — DPA